Nicholas' grandson, William L. Andrews, knew his grandfather better than his father because his father died when he was only eight years old while his grandfather died in 1934, when he was 17. William L. Andrews, Jr. told his wife, Elizabeth Jane Early, that at one time he got into trouble with his grandfather for throwing something in the living room of his house. Nicholas told his grandson to go out to the wood-shed and "get a hickery switch for me to whip you." His grandson brought back the switch and his grandfather said, "I could never whip you." He said his grandfather was very tender that way.

William Lafayette Andrews, Jr - Nicholas had a stroke or something when he was hitching up the horse, in the summer of 1934, late summer or spring. They had a funeral right here on… I remember it was the summertime and we had it on the front porch [WL Andrews Jr's farm, what is now the farm at 1448 New Columbia Highway, Lewisburg], closed in here at the house and then I don't know if they had a funeral at a church down there or not, but… He was actually living here at the time. He had been here a year or two, maybe three. He was living here with Aunt Myrtle. That was his daughter.

My grandfather had gone out to the back lot [on his son William L. Andrews, Sr.'s farm] or had been there and came back and saddled up his pony to go to town, but I heard it second hand, from Paul. He got sick and laid down and died. He was 80 years old in 1934, in the middle of the depression. But I don't remember too much other than that. Maybe if I had some prompting.

WL Andrews - My grandfather died just right at the worst time of the depression. He died in 1934 but that farm sold for about $3,500.00 and then it had to be divided up. Yeah, the whole farm down there. I imagine it was close to 200 acres, I'm not sure. It's got all that land across the road that's rocky. We used to call that the Nation. Paul (Harris) and I used to play back there – get up in these big trees and then ride them down, certain kind of trees you could ride down to the ground & then go back up. They sold the farm & divided the money. I think I got $200. He died & they sold it. Uncle Bryant I think was still trying to farm down there a little bit.

I don't think the Johnson's bought Nicholas' farm when they had the sale.

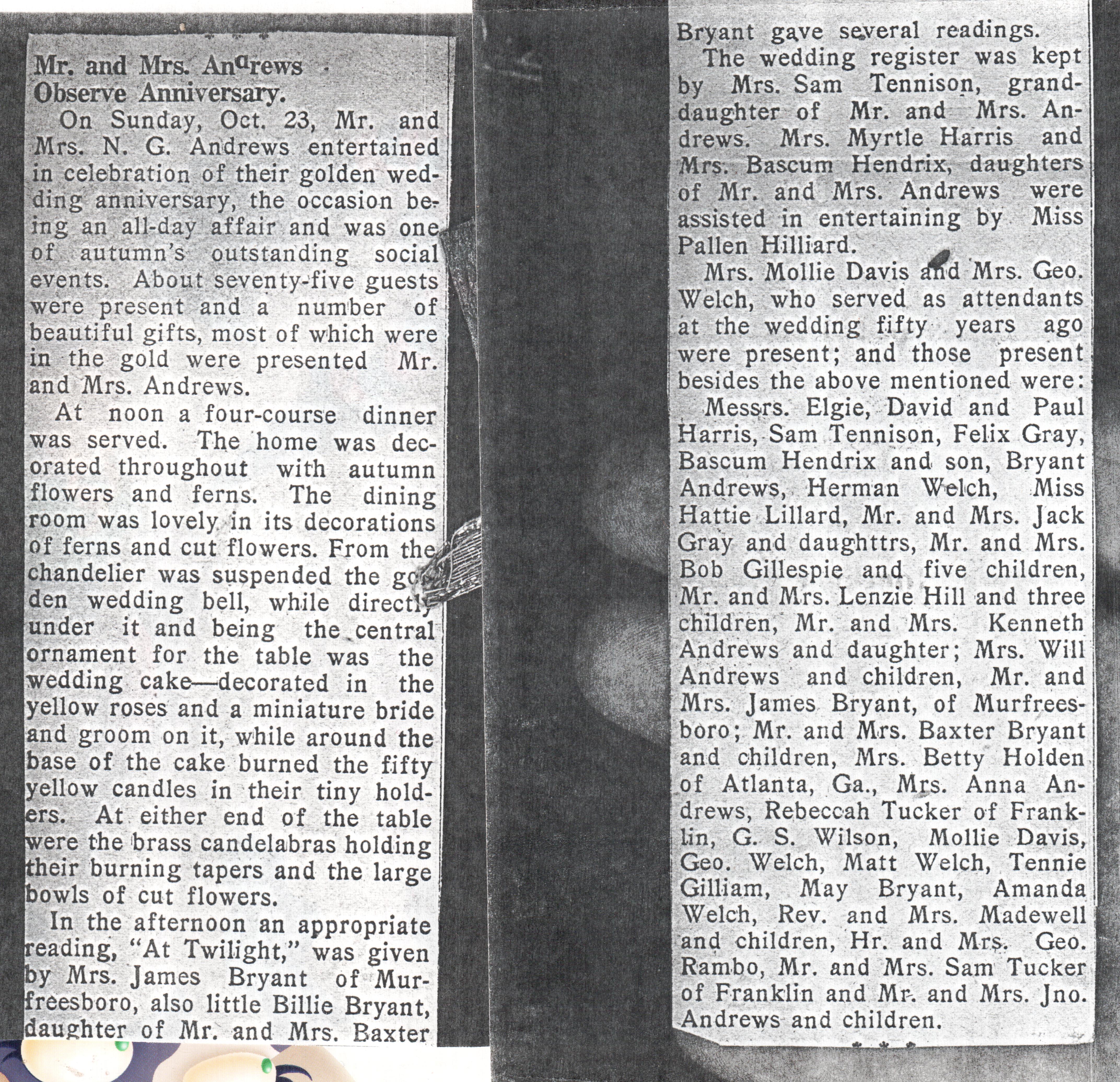

They had their golden wedding anniversary in 1928 shortly before she died. But I remember that. We have a family reunion then. But the family all lived pretty close. That is the ones down here. My mother's people up there – they all lived pretty close to Fairfield except my mother's sister, her name was Mertyl too, and they lived up in Paris, Illinois, between Fairfield and Chicago, quite a bit further up north, right near Terra Hote, about 15 or 20 miles for Terra Hote, Indiana. They lived on a farm up there. A lot of cherry trees. The boys all farmed.

Email from great-grandson William Xavier Andrews:

John, I audio recorded a conversation with Rufus Owenby around 1977 or 8 when I was doing a story on Silver Springs for the Daily Herald. He had a lot to say about a young black man by the name of Tom (I can't remember his last name but it is on the tape if I can ever find it).

Tom and his wife lived in the Verona area of Marshall County and some members of the Knights of the White Camilia periodically gang raped his young wife. As he told me the story, one day when they came for his wife, Tom ambushed them with a shotgun, shooting out the eye of a Liggett (can't rememer his first name) and shooting up the arm of another. The names are all on the tape. Apparently Tom hid out for several days and sent his wife to stay with relatives - I believe in Fayetville. Rufus told me that great grandfather Nicholas Andrews was hiding Tom out while the Knights (like the KKK) were looking for him. According to Rufus, our great grandfather told the men that he knew why Tom ambushed them and that he would not be a part of their vigilante justice. Despite this help, Tom was eventually discovered and taken to Berlin Hill and lynched. It was around 1900 and Rufus showed me what remained of the dead tree stump where his father took him to see the tree not long after the lynching. Because of the long list of names of those involved in the rape and because many of their descendants were still around the Berlin area, Rufus made me promise that I would not relate the story or write about it until after he died. He was 80 when I talked to him so I know he could no longer be around. Until I can find the tape, I won't be able to do much with the story. I've written about it somewhat in the Arrowhead Field but, as I told you, I have only had time to type up one chapter on the word processor from an almost undecipherable script from pencil (the way I wrote the book). With luck I'll find the tape.

I can remember one day when I was accompanying Milton Evans when he was squirrel hunting, he told me about the lynching of Tom in Berlin but, as I was so young, he didn't go into any details.

I don't think I have any pictures of Nicholas' house before it burned down but I can take some photos of the fireplaces. Perhaps you and I can take the kids over there to get the photos. I do have a great shot of the house at Silver Creek and I have a couple of B&W photos of the inside of Grandfather Andrews' store/post-office. I'll see if I can find them for you when you get here in July.

ANOTHER EMAIL ABOUT A DECADE LATTER:

To: David Andrews

Re: Your Article

.. What about an expansion of the piece [with what I] did on the lynching of Tom Partley in the 1890's? From what the Octogenarian told me in 1976 about the event, one of the people who lost an arm by the shotgun blast by Tom when the Knights of the White Camelia came to gang rape his wife is buried not too far away from where Daddy is buried now in the Andrews-Liggett Cem. He told me that Great grandfather Andrews (Nicholas) ordered the Knights off his land when they came looking for Tom after the shootout. He had a shotgun in his hand and he said he knew what the commotion was all about. He must have been an admirable man for the time. Anyway they found Tom hiding behind the church in Verona and took him to Berlin Hill where he was lynched. I'll try to find a copy of the original transcription of the audio tape I made of the interview in 1976. The old man's name was Rufus Owensby. When I saw Karl Johnson a few years ago, he told me that he could show me where Ralph and his wife are buried, Owenby but I don't think he's buried in Andrews-Liggett. The Liggett who was shot by Tom on the night that the Knights of the White Camelia rode up to gang rape Tom's wife is buried at Andrews-Liggett. It would make for some good photos by you. Talk to you soon. Your very intelligent older brother Willy X

Nicholas' granddaughter through his son Kenneth, Martha Thompson Andrews, said that Nicholas' horse was named Dimples and that Nicholas would ask the horse how many ears of corn he wanted and he would scrape his hoof on the ground for the number of ears he wanted.

When asked what Nicholas was like, Martha said that he favored his son W. L. over the others and W. L., Jr. and Sara over his other grandchildren. She said that W. L., Sr. had promised her father Kenneth 1/3 of his grocery business if he joined him in running the grocery store. She said that W. L. never gave Kenneth this, but said it might have been because W.L., Sr. died early.

Martha recalls living for about two years at Sally and Milton's house, a black family who lived on W.L. Andrews, Jr.s farm and milked the cows.

She said that William Vaughn Andrews' middle name was really Varney. His tombstone has a mason symbol on it.

She also confirmed that Nicholas' son, Bryant Andrews, did get his tongue stuck on a pipe and this caused his lisp.

William Lafayette Andrews, Jr. said that when he got home from the Army, Bryant met him at the train (?) station and he gave Bryant his long Army overcoat. Bryant never did very well financially and he said Bryant wore that coat everywhere after that.

Martha also said that Horace Andrews, the brother of Nicholas' father, built the corner kitchen cabinet that was in Nicholas' kitchen and then in Nicholas' grandaughter, Sara Andrews', kitchen when she died, the one that Bill and Claudia now have. Horace was Jones Andrews' second oldest child, William Vaughn Andrews was the oldest child.

The family graveyard, called the Liggett-Andrews Cemetery, is on a rise on Nicholas' farm on Route 431 between Lewisburg and Berlin where he, his wife, his son and others in the family are buried. The house on his farm continued standing until lightning hit it in the late 1990s or in 2000 and it burned down leaving only the two fireplaces standing. The two fireplaces were taken down July 29, 2002.

Wedding Party·

Berlin, Sept. 16 - On Thursday evening the hospitable country home of Mr. and Mrs. Nick Andrews on the Franklin Pike was thrown open to forty invited guests to welcome the wife of their son, William, who arrived with hs bride on the 6 o"clock train from Fairfield, Illinois, where they were united in marriage Sunday evening September 16. At 9 o'clock an elegant menu was served. Mr. and mrs. Andrews were the receipants of numerous and costly presents and their many friends wish them a joyous and prosperous wedded life.

Interview with Grandaughter Sara Josephine Andrews, Spring 1999:

I had a beautiful childhood. I was saddened when my father died when I was 16. I had a long illness when I was in first grade in school. I had a fever and my grandparents from Illinois came down because they didn't think I would live and what thet did is hold a mirror over my mouth to see if i was breathing. They had a nurse from St. Thomas in Nashville come down to Lewisburg to look after me. And they put a nettle in there and if it closed up, I was living I guess. I came out of the coma and said I want a drink of water from grandpaw's (Nicholas) well.

Grandpaw's house used to be up on a hill but they've done something to the highway so that it isn't anymore - its level with the road. It was kind of L-shaped. The front of it had a parlor and a hall that went through there connected to a room they called the family room and my grandparents had a bed in there. They had a fireplace and they'd keep warm by the fireplace And they also had a stairway, not from the family room, and the girls would sleep up there at night. When i was little one time by myself, they let me sleep in the room where they slept. They called it a lounge bed. They had a twin bed and I sleep on it now. [Sara's nephew and his wife, John and Sue Andrews, were given this bed and a couple of Nicholas' dressers after Sara died in 2002 and they have slept on that bed ever since.] They had a veranda that went around the front of the house. They had a stairway left the hall in the back that went to the dormatory and the boys would sleep there.

Granddaughter Sara Andrews:

I came out of the coma when I was about in first grade] and I said I want a drink of water out of Grandpa's well.

That was the house on Franklin Road, the two story white house, no not in Silver Creek, the one with Andrews-Liggett cemetery on it, Nicholas' well. It was beautiful. It used to be kind of on a hill, but they've done something with the highway and they kept it up beautifully. And they had a big house. It was kind of L-shaped. The front of it had a parlor and a hall that went through there connected to a room they called a family room and my grandparents had a big bed in there. That's where, they had a fireplace and they'd keep warm by the fireplace. And that's where a stairway that went up from their family room and the girls would sleep up there at night.

But when I was little, there one time by myself, they let me sleep in the same room where they slept. They also had this, they called it a lounge bed. I have it, used as a twin bed, and had the ______ like it and I sleep on it now.

But the boys, the house was like an L, and that went from the family room to the dining room and the kitchen, and then they had a veranda that came all the way around here, and a veranda that came all the way around the front of the house, and the boys went up there to their quarters in a stairway that left the hall in the back and they had like a dormitory style…

Well I say boys. My grandfather and grandmother lost their first boy and his name was Jones. And I think my grandfather's mother was named Lucy. His father, someone in the family was named Jones. Jones and Lucy were Andrews. But they had their first child, Jones was just an infant and died from a childhood disease. Little Jones. We always got to his little marker at the grave and put some flowers or something, but you can hardly read it. I can't tell.

They had, I believe they had five, but they must have had six because my father was the oldest and Aunt Myrtle was second, Uncle Bryant was next, no, I don't know the order really. There was Aunt Lou and Kenneth and Bryant and William, my father, William Lafayette Andrews. There were five left I think, and they lost Jones, the first one. And that's Aunt Lou's daughter-in-law who came today. If Jones had lived they would have had six. This paper tells about Tennessee Andrews. Her husband was named William Vaughn. And I've got something out of a book that I can show you.

MARTHA THOMPSON ANDREWS:

And mother loved milk, so she asked Pappy Andrews [Nicholas], she said, "Will you let me have a cow?" So he did and we had 2 chickens and she milked that cow and we had the best whipped cream and strawberries were 10 cents a quart.

Well, I always thought he was partial to Bill and Sara. Well, your granddaddy was his favorite. His sister told me that.. My father was the baby, but your granddad was the oldest.

Daddy and my mother were in Cleveland, Ohio working and had a pretty good job and he called and told him that if he came home he'd give him a third of the grocery store, but he didn't. So Daddy came home and worked for him, but he never gave it. [Pause] It might have been because he died. I have no idea how long they worked together. I was never told that. But I remember where the grocery store was. I was born around the corner and it wasn't a grocery store then. The old bank, 1st National bank right there on the corner is part of the court house now. Ok, you go around that, that used to be called the Belfast Road. Well, right at end where the bank drive-in is there is the house I was born in.

Nicholas was out here saddling up Dimples, harnishing him I should say to the buggy. He's say, "Dimples, how many ears of corn do you want and the horse would use his hoof to scrape out the number of ears.

And mother and I were living in Columbia and we'd come to visit. There was a toll house down here on Franklin Road and Pappy would meet us at the train station and bring us back to the farm. And there was a toll house. I don't know how much you'd have to pay. William, do you remember that? Do you remember the toll house that was on Franklin Road?

WLA – Yeah. Right about where the bridge is.

MT - And he was putting the harness on, hitching Dimples to the buggy when he died of a stroke.

I remember they brought him in and put him in that room. He died in the center bedroom.

JEA – Pappy – that's Nicholas I guess. Do you remember much about his personality?

MT – Well, I always thought he was partial to Bill and Sara. Well, your granddaddy was his favorite. His sister told me that.. My father was the baby, but your granddad was the oldest.

Daddy and my mother were in Cleveland, Ohio working and had a pretty good job and he called and told him that if he came home he'd give him a third of the grocery store, but he didn't. So Daddy came home and worked for him, but he never gave it. [Pause] It might have been because he died. I have no idea how long they worked together. I was never told that. But I remember where the grocery store was. I was born around the corner and it wasn't a grocery store then. The old bank, 1st National bank right there on the corner is part of the court house now. Ok, you go around that, that used to be called the Belfast Road. Well, right at end where the bank drive-in is there is the house I was born in.

MT – Nicholas was out here saddling up Dimples, harnessing him I should say to the buggy. He's say, "Dimples, how many ears of corn do you want and the horse would use his hoof to scrape out the number of ears.

And mother and I were living in Columbia and we'd come to visit. There was a toll house down here on Franklin Road and Pappy would meet us at the train station and bring us back to the farm. And there was a toll house. I don't know how much you'd have to pay. William, do you remember that? Do you remember the toll house that was on Franklin Road?

WLA – Yeah. Right about where the bridge is

MT – And he was putting the harness on, hitching Dimples to the buggy when he died of a stroke.

WLA – Out here. Yeah.

MT - I remember they brought him in and put him in that room.

WLA – He died in the center bedroom.

William L. Andrews, Jr. never met any of Nicholas' brothers and Sisters.

_____________

William L. Andrews, Jr. never met any of Nicholas' brothers and Sisters.

Nicholas' grandson, William Lafayette Andrews, Jr., knew his grandfather better than his father, his father having died when he was only eight years old and his grandfather dying in 1934 when he was 17. William L. Andrews, Jr. told his wife Elizabeth Jane Early that at one time he got into trouble with his grandfather for throwing something in the living room of his house. Nicholas told his grandson to go out to the wood-shed and "get a hickery switch for me to whip you." His grandson brought back the switch and his grandfather said, "I could never whip you." He said his grandfather was very tender that way.

Feb. 17, 1910-the County Board of Education authorized the Chairman of the Board, Mr. S. T. Hardison to appoint a committee to receive plans and bids for motion of a schoolhouse at Old Berlin. April 4, 1910, the Committee of the Schoolhouse at Berlin consisted of N. G. Andrews, T. T. Hardison, and F. H. Gray submitted plans to estimate on building. The Board decided to appropriate $1,000 or as much to be needed to erect a school building at that place. The County Board was to furnish the same with seats. The school building was to be completed by July 15, 1910. On July 4, 1910, Mr. E. F. Liggett was elected principal and Miss Mary Gentry, assistant. The purchase of 40 desks for Berlin School was made at this meeting. Amoug the first group of students in 1910 were Kenneth Andrews and Bryant Andrews.

See, my grandfather had another farm down- I think he got it because somebody failed to pay it off or something- down, runs parallel with the highway going to Columbia here, but it's over in the hills, over to the left there. He rented it out for a long time to the Agnues, or maybe they were neighbors. I've forgotten. And then when Bryant finally did marry, of course that was way after my grandfather had died, he lived down there for awhile and then I don't know whatever happened to it. It was a hill farm so not a whole lot of acres I don't think.

I remember when I got out of the Army, Bryant never had much, and I had my old Army overcoat and I gave it to him and he wore it. He's the one, he had a slight lisp or something and they tell me that when he was a little boy – see, my grandfather had that shed that had a creamery and they sold the cream and had a separator that separated the cream from the milk, and then there was a water pump right in the center of it out there and it was all covered you see but it was open so in the cold weather it would get cold and that old handle on the pump would get cold too and I heard that he stuck his tongue on it and it froze to it and I bet when they pulled him off of it, it tore his tongue. (Martha Thompson said this story is true.)

JEA – So after your grandfather died, what did you say happened to his farm?

WLA – Well, when he died it was sold and all of the children got a little but, Sara and I got some. May have been $300 or $400 instead of $200.

JEA – Now the fireplaces in his home were so close together, was there a room between them?

WLA- He had a fireplace in the parlor; old houses used to have parlors –well, it was more of a company room to visit. And then the other side was a living room. There was a hall in between and two rooms upstairs, one called the "boy's upstairs" and the girls and it had different steps going up to them. In the dining room there was a fireplace. There was a hallway between the living room and the dining room and then a kitchen. (The fireplaces were torn down July 28, 2002.) Well, there were two hallways, a hallway going from the front door between the two fireplaces and then a hallway on the other side of the living room.

[Looking at Picture]

Here's my grandfather Bryant. That's my grandmother's father. He looks a little like Cullen Bryant, you know, the poet. That's my father; that's my Aunt Myrtle; and that's Uncle Kenneth and that's Aunt Lou and that's Bryant. She was only about 65 but looked older. But everybody did in those days.

When Grandpa (Nicholas) was a little boy, 6 or 7, maybe a little later, I think they lived on the edge of town up here. Actually, it was on the Old Columbia Highway I used to go… but it's right there before you get to the, not the new high school, the new high school too. They're all together now. It's an industrial school now. Nicholas lived there when he was a boy. Just when he was real young. It wasn't in town then. It was way out. I don't know if it was a farm or not, but they had some land. But I don't think it was a very big farm.

WLA – Margaret Cannon's son was in law school with me. He was interested in aviation law. He graduated after I did. And that's Elizabeth Derryberry's [Eddy Derryberry's mother] and John R. Andrews; that's the one I played with, and that's her children. She had 4 children.

JEA – So Anna Andrews was the daughter of Tennessee Tucker.

MARTHA THOMPSON INTERVIEW:

Jimmy was Nicholas Andrews' brother.

There's Cora Gray right there.

She [this woman who wrote Martha for family history] called Peggy, David's daughter. She lives in Murfreesboro. Her father was Elmer Douglas Andrews, son of Jimmy. Peggy told her to write me.

J.D. Andrews is Jimmy Andrews.

Cunningham Cemetery between Berlin and Verona.

That's Uncle Bryant and Daddy when they were in school in old Berlin in 1910.

Uncle Bryant never had any children of his own but he loved them. He didn't marry until real late in life.

WLA – MR. WILLOUGHBY, WHO DOES UPHOLSTERY WORK, HIS WIFE TOLD BETTY…

MT - TENNESSEE TUCKER – SHE SMOKED A PIPE.

THE NAME LANIER IS PREVALENT IN OUR FAMILY. I'VE GOT A PICTURE OF DADDY AT PRICE-WEBB TOO [KENNETH].

I WAS IN HIGH SCHOOL WHEN MY PARENTS LIVED IN SALLY AND MILTON'S HOUSE. I'M 84 YEARS OLD. THAT WAS 1934. THEY PROBABLY LIVED THERE A COUPLE OF YEARS. AND THIS WAS A MILE AND ½ FROM TOWN, SO IT WAS KIND OF like the country. . And mother loved milk, so she asked Pappy Andrews [Nicholas], she said, "Will you let me have a cow?" So he did and we had 2 chickens and she milked that cow and we had the best whipped cream and strawberries were 10 cents a quart.

Berlin Tennessee

An Historical Prospective

This is a compilation of various articles that have, over the years, appeared in the Columbia Daily Herald, Marshall County Post, Marshall County Historical Quarterly, Berlin's Tennessee Homecoming 1986 Publication, and other various publications. Also, there is some additional local oral history thrown in for good measure.

There contains herein two articles written by William X. Andrews of the Daily Herald appearing July 17, 1976 and September 9, 2006. The 1976 article by Bill Andrews is one of the more comprehensive articles on the Berlin Tennessee area, its history, and people.

According to The Goodspeeds History of Tennessee, before the War Between the States Berlin was once incorporated and was even larger, population wise, than the present county seat of Lewisburg.

The Maury and Marshall County Berlin area of today consists of the Berlin General Store, Berlin United Methodist Church, a fully equiped volunteer fire department, the Berlin Springs Park, area cemeteries (Ownby, J. Thad Ownby, Andrews-Liggett, Boyett, Whitesell, Cunningham), and dozens of homes. During the campaign season politicians can be found attending the many activites at the park and fire hall..

________________________________________

FYI, the name is pronounced "Bur" "lun" by the locals, not "Bur" "lynn"

A Return to Berlin's Big Springs by great great grandson William Xavier Andrews, about the area in which he lived:

Thirty years ago, as I was waiting for my full-time college teaching assignment to begin for the fall, I worked for this newspaper and had, among other things, responsibility for what was then the weekend magazine "Focus on Southern Middle Tennessee." Under the editor, Jim Finney, I was given considerable latitude in choosing my subjects and doing my own photography and layouts. It was a fun job.

Of the stories that I did, the one I most remember was a five-page feature on the Berlin community, an article that appeared in the Herald on July 17, 1976. I had some strong emotional attachments to the area because my great-grandfather had a farm there and Bit Hardison, owner of the general store, sometimes drove me to St. Catherine's school when he made his Monday morning egg-delivery runs to Columbia. I can remember as a first grader plucking feathers from my Eaton suit as I entered the school.

My piece on Berlin began when Marshall County historian Ralph Whitesell introduced me to octogenarians Paul Finley and Rufus Ownby, gentlemen who must have had the patience of Job as they sat with me for hours on porch swings and rocking chairs. With audio recorder and camera in tow, I interviewed them and dozens of other people in the community. Looking at the yellowed pages of that article today, it is apparent that many of those I met are now deceased and the children I photographed are in their forties.

Mangus Hardison took me to the famous Berlin Spring and pointed to the spot where James K. Polk and Andrew Johnson delivered campaign speeches. Paul Finley told me of his great-great-grandfather Frederick Fisher who settled in Berlin many years after he was wounded at the Battle of Kings Mountain during the Revolutionary War. Shown a 1912 high school graduation portrait of fifteen young women at the Spring, I noticed that one of the girls was my Aunt Annie Lou Andrews. On the reverse side, along with the names of the graduates, was a notation indicating which of the girls died in the 1918 influenza pandemic. It was a photograph that was at once beautiful and sobering, a visual commentary both on the beauty and the precariousness of life.

At the home of Rufus Ownby, the eighty-year-old man recounted local history while his wife Ruby plied me with tea and white rabbits scurried about. Of the many stories he told, the most disturbing was his account of a late-nineteenth century lynching on Berlin Hill. According to his account – and it's the only one I've heard, several members of the Knights of the White Camelia went to the home of Tom Partley where they sexually assaulted his young wife. Realizing that as an African-American he had no legal recourse, he decided to take matters into his own hands. On the next occasion when the Knights rode up, Tom fired on them at close range with his shotgun. One rider was blinded and another lost an arm. For a time and with the assistance of farmers both white and black, the fugitive was able to elude capture. He was eventually caught behind the Methodist Church in Verona and taken to Berlin Hill where he was lynched.

The storyteller was born in 1896 and heard the account from his father. After Rufus gave me the names of the assailants, he asked me to do him a favor. He wanted me to wait until after he died before telling the story and revealing the names. When I asked for an explanation, he said that children of the vigilantes still lived in the community and that they should not suffer for the transgressions of their parents.

On Labor Day, curious to see how things had changed in thirty years, I drove to Berlin, about eight miles north of Lewisburg. I was pleasantly surprised to discover that what in 1976 had been an unremarkable and neglected area around the Big Spring has been transformed into an attractive and shaded park with picnic tables and a bridge. I was disappointed, however, in that I had the whole place to myself, on a holiday no less. It was a far cry from the Sundays and holidays described by Tom Crigger back in 1976 when he recalled throngs of picnickers, swimming children, and dozens of saddled horses and parked buggies around the hitching posts.

Driving south on highway 431, I came to the cemetery where Paul Finley was buried, his gravestone within sight of the ancestor who fought with Morgan's Regiment at Kings Mountain. That grave was just few feet away from the headstone of my great-grandfather Nicholas Andrews who, according to Rufus, stood with shotgun in his hand when he ordered the Knights off his land in their search for Tom Partley. I passed the graves of some of the girls of 1912, those whose beautiful white dresses reflected in the spring waters. And I saw the grave of one of those who Rufus named in the crime against Tom and his wife.

As I was leaving the cemetery, I noticed that Carl Johnson was on his tractor pulling by me with a load of sorghum. Like Rufus Ownby and Paul Finley before him, Carl is one of those of a later generation whose memory can be tapped for detailed genealogical information on Berlin. Over the din of his tractor motor, he spoke fondly of the Hardisons, of Paul Finley, of Ruth and Rufus Owenby, and of my people. He also described the location of various cemeteries where I might be able to locate their tombstones. I left wondering if there might be a grave marker somewhere in Marshall County for Tom Partley. It's too late to ask Rufus. Perhaps others somewhere can tell me more of Tom and his family. Stories need to be told and names remembered. It's a sad commentary on the fragility of memory that they are not.

________________________________________

From: John Andrews

To: [email protected]

Cc: David Andrews ; [email protected] ; [email protected]

Sent: Saturday, October 01, 2011 7:56 PM

Subject: Berlin, Marshall Co, TN history; Tom TarpleyBack

Bill, I can't thank you enough for your email. I'll try to find the newspaper article and email it to you. My brother Bill wrote it, and I'm copying him here so that if he has a copy handy he might send it to you.

I do not have, and would love to have a scan of the Berlin Community History. Thank you very much.

Are you the Bill Allen who ran a tire changing machine manufacturing plant near Smyrna back in the 1970s? If so, I interviewed with you for an accounting position when I returned to Tennessee. I really enjoyed our interview but took a position with an Aluminum extruder in Columbia instead. Thanks again Bill. It was very good hearing from you.

John

John,

First, a couple of apologies. I'm sorry I failed to remember our interview ~ 35 yrs ago; when I sent the e-mail to you''. .. I do (now) remember the interview & a few of the things we discussed (as I recall, you were at St. Louis U when I was in suburban St Louis at my first job out of college?). I just realized that you're an attorney (L& W represents Carlyle Group who bought/owned/sold the business I worked with 1986-2007)

I did some more research on Tom Tarpley.

Death by the White Caps

PULASKI, TENN. April 25.—[Special]—Tom Tarpley, of Verona, was notified by the White Caps, two weeks ago to leave that locality or be hung. He disregarded their threats and mysteriously disappeared today.

His body was found suspended in the woods, and had been dead for several days.

From the Burlington Hawkeye (IA), 13 May 1893

Hanged by White Caps

Tom Tarpley of Verona, Ga., -was notified by whitecaps recently to leave that locality or he would be hanged. He disregarded the threat, and at the end of the time he mysteriously disappeared. Diligent search was made for him, but no trace could be found and it was concluded he had obeyed the order at the last moment. A day or two ago, while Joe Tillman was squirrel hunting near Berlin, which is not far from Verona, he was walking through the .woods looking up into the trees, when he came face to face with Tarpley, apparently standing erect. He soon saw that Tarpley had been hanged and dead for some time. The stretching of the rope and body had let his feet to the ground. The whitecaps had executed their threat.

I also found the below report given by my father's 1st cousin -

Excerpt from a report given by Margaret Allen Jordan, November 4, 1973, to the Marshall County Historical Society on the Berlin community, regarding Dr. Thomas Alexander Allen)

Daddy (i.e., Margaret's father, Kenny Argyle Allen, b 1880, son of Dr. Thomas Alexander Allen) used to tell when he was a little boy that the White Caps hanged a Negro in the woods this side (i.e., the Lewisburg side, or south side) of Berlin Hill. It was several days before he was found. It had rained in the meantime, the rope had stretched and his feet were touching the ground, causing his knees to bend. I don't know whether they sent for my grandfather and Daddy went with him or whether he was large enough to go out of curiosity, but anyway he saw him. It made such an impression on him he never forgot it and didn't want to go back to the place where it happened.

In reviewing the medical account records of my g-gf, Dr. Thomas A. Allen, it appears that the Nicholas G. Andrews family were his patients in the 1883-1905 period. It appears that the Nicholas G. Andrews family were somewhat regular patients; however, it appears that they did not use the services of Dr. Allen for child birth (not unusual; the charge was generally $10, a rather stiff fee for that day). In fact, I see a charge in the ledgers for "1 visit at night, Ken" on 11 Apr 1905, with payment by cash on 5 June 1905. I suspect that Kenneth Allen Andrews could have been named with regard for Dr. Thomas A Allen, or for some other Allen who likely lived in/near Caney Spring TN (where my g-gf was born & lived before he came to Berlin).

Bill Allen

Nicholas' Grandson and Great-grandson's conversation about hiding the slave Tom:

JEA: Bill, you said you did some research and you were fearful about slavery in the family, you know, that we were slave owners.

WXA: I don't remember saying that.

JEA: …and then you found out that Daddy's grandfather…

WXA: Yeah, saved a black man, tried to save. It was unsuccessful. The guys name was Tom.

JEA: How did you find out about it.

WXA: Rufus Owensby told me about it, that your grandfather hid him out for awhile. And then they, I mean they came to his door and said, where is Tom, and your grandfather said, I don't know. But apparently he was hiding him. And they found him. See they had gang- ____ Tom's wife. They were Knights of the White Camillia. This was around 1900 and they… I think that was kind of neat though. He hid him out. Now what happened, he went back to visit his wife and they lived close to Verona church and they caught him over there and took him over to Berlin Hill and lynched him over there. And Rufus Owensby told me, he was something like 80 years when I interviewed him 25 years or so ago. I interviewed him in 1976. When I made the tape; I have the tape at home, an hour long tape, he said Bill, whatever you do, I want you to wait until I die before you publish this. I know these people. He said, so and so Liggett over there got his eye shot out he was one of the _______ [the one's who abused Tom's wife] and this other guy got his arm blown off. I mean this black guy Tom opened up on them with a shotgun. Your grandfather tried to save Tom. He was one of the good guys.

JEA: Did you know that our family held slaves though?

WXA: I didn't know.

JEA: There's this book in Columbia about Marshall County and it has information about the prominent people of Marshall County and it says one of the wealthiest was Jones Andrews, owned 500 acres of land and he was good to his servants and it said he brought up his children well, educated them well. Nicholas would have been his grandson. Aunt Sara had it from a book in the Columbia library.

WLA: The Goodman boys, you know there's a cemetery back there and there's a rock wall around it, and they think, they're not sure, but there are some graves outside the wall, they think those were the slaves outside the wall.

WXA: Where was Uncle Bud buried? Was he buried on their property.

WLA: I don't know.

WXA: When did he die? About 1960? Somewhere we have a picture. And you made a movie. Was he alive in 1959 when you got the camera? 8mm but he's in the shade. You don't see him very well.

WLA: I'm not sure when he died. I know Milton died in '65.

WXA: I know John broke down and started crying when he got the word about Milton.

WLA: Back when we were at Tyne, they got their water down here, and for some reason someone turned off the water. But it was open. We never did lock it. But Elgie called me. Elgie came by and I didn't know anything about it. We came back and forth on weekends.

JEA: Was it Mama who put electricity in that house or was it both of you? Because they didn't have electricity until '55 or '56.

WLA: We got it here in '37. Uncle Kenneth lived up there for two or three years. Back during the depression during the '30s.

WXA: And it was the oldest house in Marshall County?

WLA: Now, I'm not sure about that. Ralph Whitesell said it was one of the three oldest houses. … and they said his house was two miles north west of Lewisburg and it sounds as if that's about the same distance. He was one of the first counselmen or whatever you call it for this county, county administrator. It use to be on that, you remember that old log house, it use to be the old courthouse, where the road parts going to Cornersvillle...

WL Adrews, Jr.: [Nicholas' farm when he moved here [to his son WL Andrews' farm] - or after he died, was sold then and just the money divided up. And, of course, I bought my electric guitar I think with the money I got. That was his [Nicholas'] original farm. It was where – see, we were living there [Silver Creek] when Sara was born. My father and mother were living at Silver Creek when she was born, but I think she was born down there (at Nicholas' farm) at that time. I don't think they were born in hospitals then I guess.

JEA – But how did Nicholas happen to buy his farm? That wasn't a part of his father's farm was it?

WLA – I don't know.

JEA – But he lived there from an early age, right?

WLA – I don't know whether anybody else in the family lived there before or not. I just don't remember. I kind of think he bought it. I may be wrong.

WL Andrews Jr. about his Grandfather and his Farm:

But he was a fairly progressive farmer for those times. He was the first one to have a car down that way. It was a T-Model Ford, but he was one of the first ones. That was long before rural electrification came along in the mid-1930s. We got electricity here [WLA's father's farm] in 1937. But long before that down there, he [Nicholas] had Carbide lights. And I remember there was a great big tank, cylindrical shaped buried down in the ground – the top of it you could see. Then there was carbide, was put down in there – I don't know how often you had to do it. Then there was water dripped on it and it foamed and made gas. Remember how miners used to have carbide lights. Then there would be lines that went into the house and there would be gas fixtures just for lighting. That's all you could do with it back then.

That was a beautiful place down there back then compared to what it is now because the road was way down and the house was on a hill side and there was a gully or ditch where the water would run when it rained. And we took a ride over the culvert and then up. It was quite a bit further from the road. When they built the road, they built it up and moved it over and of course they widened the whole thing. The road now is where the fence to the yard used to be but back then it was on a hill. He kept things up to date, painted, two barns, sheds. He died in 1934 abd they sold the place. Since my father had died - he had been dead 10 years when my grandfather died – when the farm was sold, Sara and I had my father's part. I think it sold for $4,000 and I got $400. 1938. I bought an electric guitar with part of it. I was 22 . Carter McClellen who was killed in World War II, was a very good musician. He and two other medical students – he was a medical student too – a young fella played the drums, Carter played the piano and saxophone and trombone, clarinet. We got a contract in 1938 before World War II, even before Hitler invaded Poland and a year after Czechoslovakia. And we got passage on the Europa to Europe and we were going to play on board and you know I wasn't much of a musician, I still can't read music, but I played the piano a little bit and the electric guitar, kind of a fill-in back in those days. We were going over on the Europa. Then we'd be on our own over there for a month, a couple of months. And then we'd come back on the Dorsa, both white-star steamers. We'd get passage both ways for playing and then little jobs while over there. But it all fell through because Carter got a job with the Francis Craig orchestra, pretty well known band back then. Francis Craig wrote "Red Rose" which was his theme song and we didn't go. But it would have been a nice experience.

About the Community in which Nicholas Andrews Lived by Grandson William Xavier Andrews

PAGE 6 --THE DAILY HERALD, Columbia, Tennessee, Saturday, July 17, 1976

Berlin Spring

Today and Yesterday

By BILL ANDREWS

Campaign Trail - Berlin, Tennessee 1844

In the open shade of the towering oaks and poplars which formed something of a rough, natural theater, the crowd for the most part listened intently— particularly those who thronged about the speaker's stone rostrum. Bounding this natural enclosure on the south and west was a precipice-like formation of massive boulders and rock walls. To the east and north were the old trees which would not be cut for timber for another sixty years. For some in the crowd sitting leisurely along Cedar Creek or at the mouth of the famous Big Spring, the words of the distant James K. Polk were barely audible, drowned out by the antics of youngsters splashing in the cold spring waters or climbing through the overhanging branches. There was a definite picnic-like atmosphere to this political gathering which even well polished rhetoric and heated exhortations could not dispel. If the eloquence of Polk's words did not fall upon every ear or stir many emotions, it was only because most people in Old Berlin considered the shady Big Spring clearing more a playground than an arena in which to pursue serious concerns.

The forty-seven year old Polk was no stranger to Berlin. He could consider himself responsible for putting a number of old war veterans in this area on the pension rolls. As a legislator, he was responsible for getting a popular local personality, Samuel Ewing, appointed postmaster for the Berlin Community, recently a part of Maury County's eastern fringe until, eight years earlier, the new county was formed. His face was familiar here and on similar occasions, seeking other offices, he had spoken on this very spot, on the Berlin Rock.

As everywhere on the road for public office, there were the local critics and the taunting hecklers. Polk hoped that by addressing himself to the burning issues of the day, he could keep the disturbances of these pro-Whigs to a minimum. Things could have been worse. His familiar rival, Governor "Lean Jimmy" Jones could have been there in Berlin, openly sarcastic of Polk's style and mimicking his delivery. But, fortunately, Jones was in Nashville and the speaker was sure he could gain the confidence and support of these hard-working, enterprising people.

The most emotional issue for Tennesseans in this the opening campaign for the presidency was the annexation of Texas. If the words of warning issued by the Mexican Government were to be taken seriously, to pursue the course of annexation would make an eventual war with that country a foregone conclusion. Polk knew that, because the annexation question was very much related to the growing debate over slavery, he could manipulate the issue to his own advantage. His Whig opponent was Henry Clay, a presidential aspirant who was lukewarm on the subject. The Columbia lawyer and politician knew that no Tennessean was without a friend, family member or acquaintance who was now in Texas agitating for statehood. In the opinion of Polk, if he accepted the annexation of Texas a probable slave state, then his Democratic Party could always offer the annexation of the Oregon Territory as a free state, and effort which hopefully would placate both Northern and Southern sentiments.

When the speeches had run their course and the group had absorbed as much information as a gathering could in the summer heat, a number of the village elders — most of the men over the drinking age — retired to the nearby tippling house where, with a few bolting shots of good liquor, the debate could be more amicably renewed. It was ironic that, although Polk won the presidential election which followed, he lost Tennessee to the Whigs, the first such phenomenon in national presidential politics. The stone upon which the famous speaker delivered his opening campaign address was moved from Berlin Springs to the lawn of the Marshall County Courthouse in 1925. In that year Isaac Whitesell jacked up the large stone under his four-mule team wagon and attached it to the cutting pole and running gear by chain. The stone was placed across the 'street from Polk's old log house law office in Lewisburg where, it is said, the lawyer was napping, when word of his nomination for president first arrived.

EARLY SETTLEMENT

When the first surveyors and settlers arrived in the vicinity known today as Berlin, they were immediately impressed by the large spring of cold, crystal clear water which flowed into Cedar Creek and, further on, into the Duck River. It was only natural that a small, closely-knit community grew up around the Indian watering spot in the first decade of the nineteenth century. After the initial land grants to Revolutionary War veterans were distributed and divided into smaller tracts, more Virginia and North Carolina families moved into the area. The dense growth of cane was cut away, farmland was gradually cleared, and the small, smoky but livable log homes were erected. The land on which the Berlin Community grew and prospered was originally part of a 1,200 acre grant issued to a James Watt of Iredell County, North Carolina, for services rendered to that state during the Revolution. Following Watt's death, the Maury County Court of Pleas and Quarterly Sessions in 1814 divided the land into tracts of 190 acres each, the property to be held or sold by the heirs of the deceased Watt. With the 1806 Dearborne Indian Treaty opening up lands south of the Duck River for settlement, the number of families who were moving into the area were not prepared to buy these tracts from the absentee property owners in North Carolina.

Some of the earliest arrivals to the Big Spring area were merely transitory visitors, remaining only a brief period before returning to the familiarity and security of life in the East or pushing on to the West. From those families which overcame the urge to move, names such as Hardison, Fisher, Liggett, Ownby, Field, Allen, Finley, Bumgardner, and Huggins are only a few of the many which proliferated throughout Maury and Marshall Counties.

Among these early settlers in the Big Spring area were a number of veteran combatants in the Revolutionary War who resolutely worked the land given to them in grant. Witnessing in 1819 an ex-change of land involving a portion of the Watt grant was a Frederick Fisher, born in 1762 and originally a resident of Mecklenburg County, North Carolina. Census records, pension rolls and Marshall County documents indicate that this veteran of the Revolution was subsisting on a meager pension of $3.33 a month while in the Berlin area. They also suggest that Fisher was in Tennessee as early as 1809, although no surviving document can accurately pinpoint the date of his arrival in Berlin.

One document in Fisher's pension file concerns a report made by an examining physician in North Carolina which certifies that "I have examined Frederick Fisher, a soldier in the Revolutionary War who received a severe wound in the right leg at the Battle of King's Mountain and that he still continues in amble-of-attending to his occupation as a farmer." As more than the exception in those days on the frontier, Fisher, like many others, encountered difficulty in official red tape in obtaining his ymenls. As the case of Fisher indicates, bureaucratic mismanagement and bungling were also features of government in the early 1800's and the early pensioners cold make as much of an uproar then as taxpayers do today. In any case, Fisher found it necessary to enlist the help of James K. Polk to oversee his pension payments and help manage his estate. The old veteran died in 1846 and was buried in the Andrews-Liggett Cemetery where, today, a government headstone and a DAR marker note his contribution to the struggle for American Independence.

Two other Revolutionary soldiers settled with their families in the Berlin area. John Field of Rockingham County, North Carolina, was an officer in the war and John Fendall Carr served as a private in the Virginia Regiment of the Continental Line.

INDUSTRIAL GROWTH AND CIVIL WAR

When in 1836 Berlin became a part of newly formed Marshall County, the small village was experiencing an even-paced and gradual prosperity. For some time there had been talk of incorporating the business minded community prior to the Civil War but the effort repeatedly met with failure in the legislature. Although the argument for incorporation reportedly concerned the attempt to improve roads and local law enforcement, County Historian Ralph Whitesell considers the effort to have been an attempt to add a few more tippling houses (saloons) to the village's business area. not even a skirmish — in the immediate vicinity of the village and for this the population considered itself lucky.

But there were friends, neighbors and loved ones who would not return to the Big Spring at war's end and, as in other parts of Dixie, their conspicuous absence did much to drain the energy out of the life of the South during the difficult years of Reconstruction. Weathered gravestones in the Wells Cemetery near South Berlin remind the visitor that two luckless sons of the Confederacy never outlived the war, to realize their ambitions.

Magnus Hardison, 70, a direct descendant of a James Hardison who settled near the village of Dappletown (Maury County) in 1809, gave me a copy of his family history, composed by his 56 year old grandfather in 1911. The author's grandfather, Thomas, lived along Cedar Creek in the Berlin Community during the war and his ac-count of that conflict and his sentiments is revealing.

"My grandfather bought and moved to the farm that I now live on in about 1834. He cleared most of the land and, as others, he owned slaves in that day. He never accumulated much property. The War Between the States freed his negroes. His stock was stolen and his property was torn up. At the close of the war he was getting old and never made anything more except a living. Religiously, he was a Methodist, as was the rest of the family as far as I know. Politically, he was a Democrat, but I think before the rebellion, he voted the Whig ticket. He was opposed to the war yet he did not think it right for the North to free his slaves and not pay for them. If they had stopped at freeing the slaves, it would not have hurt the South so much, but they stole all the property they could carry away and burned and tore up what they couldn't carry away."

Eighty-year old Rufus Ownby referred to an incident which occurred in Berlin during the war. Although the details are very sketchy, Rufus can recall hearing the story as a youth.

"I've seen the grave down below where Tom Leonard's house is. There was a boy killed and buried there during the war. He came from the south end of the county, maybe from Fayetteville somewhere and he came to Berlin to bring some clothes and food to his brother. He was camping down near Leonard's place when they came upon him. They thought he was up to something, you know. I don't know what they thought he was up to but the question is they didn't believe him and they said, 'Let's get it over with.' They killed him and threw his body down by the creek. His daddy heard about it and came looking for him. When he found the boy, Old Man Bob Lurney stayed with him until his daddy made a box and buried him right there. They were Southerners who shot the boy but I can't remember who the boy was or anything about him. I've tried to find out but nobody now seems to know. I've been by his grave a lot. It was an orchard of peaches and apples then where they buried him."

LIFE AND LEISURE

Affairs in Berlin were generally peaceful and movement was slow during the first decade of the new century. One observer of village trends wrote in 1909 that "the Creekites are being much enlivened by listening to the graphophone over at Ed Morton's. He sets the machine going on his porch at night and the neighbors all enjoy it. Thomas A. Edison must have had the loneliness of the country at mind when he invented the graphophone. At least it is a rare and wonderful invention."

Of course, events were not always peaceful and life certainly was not dull. Rufus Ownby can recall an incident near the village saloon when in an ex-plosive outburst of argument Squire Bob Fields and his neighbor went to their homes for their guns, wishing to settle the When the two men were ready to open fire, Feilds yelled out hurriedly to his adversary, "let's stop this damn foolishness and have a drink." The two men retired to the saloon where, it was hoped, they could resolve the argument and, at the same time, add a few more years to their lives.

Years later, Frank Liggett was driving his newfangled automobile down Berlin Hill when he happened upon Wiliby Ownby's team of spirited mules. The animals caught a terrified glimpse of the strange machine and bolted down the hill, smashing up Ownby's mower and tearing up the turf along the way. The two men never came to blows but Ownby sued Liggett for damages and the case caused something of a stir in the village.

PHOTO description: The old office of Dr. Thomas Alexander Allen (1837-1917) can be seen in the foreground and the equally old smoke house stands on the western fringe of Samuel Ewing's original tract of land. Allen, a veteran of a Calvary unit in the Civil War, received his medical degree from the University of Nashville and moved to Berlin where he married Mary Fredonia Ewing, the daughter of one of the community's early settlers. The two buildings pictured here were moved from the Franklin-Lewisburg Road to its present site on the Sowll Mill Pike.

PHOTO description: Frederick Fisher, a Revolutionary War soldier from Mecklenburg Co., North Carolina wounded in the Battle for King's Mountain, was buried In an unmarked grave near Berlin in 1846. Paul Finley, a great-great grandson of the noted soldier, called attention to the burial site and, as a consequence, was responsible for having an official government grave stone placed in the Andrews-Liggett Cemetery. A DAR marker stands to the right side.

PHOTO description: A photographer appreciating the rustic beauty and scenic splendor of Berlin's natural rock formations had his young subjects pose for him before the Big Spring. Photographed in 1912 under the grotto-like recesses of the famous spring are... (on far right) Annie Lou Andrews. An indication of the severity of the times can be seen in the effects of disease in the early Twentieth Century. Within a short time of this photograph, Sallie Baumgartner (eighth from left) and her mother died of the flu -within days of each other. A brother of Kate Baker (second from left) died of the same infirmity. Medical Science and technology were only at the threshold of that progress and success which they enjoy today.

__________

Grandson WLA:

Nicholas had a car, but I don't think he drove it. Uncle Bryant did all the driving. He had a stroke or something when he was hitching up the horse, in the summer of 1934, late summer or spring. They had a funeral right here on… I remember it was the summertime.

On November 21, 2008 Carl Johnson, whose family subsequently owned Nicholas Green Andrews' farm, said that Paul and Elgie Harris had told him that there was a Green family who lived across highway 431 and on the other side of the land owned by Nicholas called "The Nation." Carl did not know if this family was related to Nicholas. Carl said that Nicholas built his home himself in about 1900 and in about 1913 a tornado hit the house and apparently blew down the two stone fireplaces because when he was growing up in this house brick chimneys stood above the roofline. Carl said that Nicholas' farm must have been about 140 acres because Carl's family had purchased another 40 acres.

Carl also said that there was a partial stone wall in back of the house that had been part of a blacksmith shop.

Paul Harris had given Carl a photograph taken of the Nicholas Andrews family in front the house Nicholas had built. William L. Andrews, Jr. also had a copy. On back it said: "Left to Right - Kenneth Allen Andrews, Mattie Gillum (Carl said this was a friend of the Andrews family), Anna Lou Andrews, Bryant Andrews, Grandmother Tennessee Tucker Andrews (sitting), son Nicholas Green Andrews with wife Sara Bryant Andrews."

December 13, 2008 - Elizabeth Jane Early told her son John, "Daddy told me that he loved his grandfather Nicholas more than anything."

From: William Andrews [great-grandson]

Sent: Thursday, April 01, 2004

To: Andrews, John (DC)

Subject: Death, Memory Loss, and Procreation by Bill Andrews

One of the more interesting observations about life these days comes from the Sound Off section of this paper. Everyone is either complaining about the new trashcans or dissing the whiners. I am reassured by all the commotion. If this is all we have to complain about, life in Columbia must be pretty good. As a sage once said "God is in His heaven and all is well on earth." All is well, that is, except death, memory loss and unwanted pregnancies. One of the great advantages of being alive is knowing that we're not dead yet. No matter how you slice it, death is a bummer. Fortunately, I still have both of my parents who, although in their eighties, appear healthy, contented and sharp as nails. For this I have much to be thankful. In fact, except for a brief stint in Vietnam long ago, I have been fortunately spared visceral acquaintance with death. It's a blessing. However, that said, I know what awaits all of us mortals. I personally have problems with those theologians who tell us that we can't appreciate life without death, peace without war, good without evil, or pleasure without pain. I have a pretty good imagination and I can appreciate all these things without experiencing them in the flesh. I can see it all in a Tarantino flick. I've never gotten a handle on pain. As a child observing my Dad using a hammer in some carpentry task, he would frequently smash his thumb (he's no Bob Vila). In these instances, he would never utter a word. He simply turned white and keeled over in a dead faint. My brother John is the same way. I've never heard either use a dirty or profane word – not once. Not even hell or damn. They just faint. Whenever I smash my thumb, fall off my horse or walk into those iron statues in front of the college library, I yell out all the cuss words I can think of. It seems to help a little – but only a little. When as a child I experienced pain, Mom would tell me to offer up my suffering to God and to "pray for the poor souls in Purgatory." This never made sense to me. I could care less about souls in Purgatory. I just wanted immediate relief for myself. Hard as I try, I've not been able to explain the purpose of pain and death. I am also troubled by the fact that, despite being created in God's image and likeness, we forget ninety percent of what we learn? And why does our Creator allow people who are so patently incapable of raising and loving children to reproduce with such profligacy? It is for this reason that I plan to have a very candid and heartfelt conversation with God on the occasion of my leaving the comfort and contentment of this world. Not wishing to offend Him or to alter my predestined spot in heaven (I'm an optimist), I will exude the most sincere respect, reverence and humility while offering three suggestions for a better world. 1. Let's just do away with death completely. It's wasteful and traumatic for the loved ones left behind. I prefer my Dad's idea about aging. We will all grow old as we are programmed to do but, once we hit an ancient and decrepit age, we will kick into reverse and start getting younger. As we are riding the down escalator toward birth, we can make periodic adjustments in our decisions based on personal experience on the way up. We will head back into a warm, womb-like shelter from which we will all emerge painlessly in heaven. We will have made all the necessary corrections. I hope God likes that idea as much as I do. 2.Memory loss is another bummer. Recently when I returned to my truck in the Wal-Mart parking lot, I climbed into the cab to discover a very strange lady with bulging eyes starring at me from the passenger seat. Forgetting where I parked my truck, I was obviously in the wrong vehicle.

Let's just fast-forward the evolutionary timetable so we can acquire cerebral power and memory capacity without altering our brain size - like going from a Pentium 3 to Pentium 4 memory processor. We get greater quality without greater size. In fact, we have an evolutionary precedent. Neanderthal brains, paleo-anthropologists tell us, had greater cubic capacity than Cro-Magnon brains and look where it got the hairy brutes. I will respectfully suggest to my Creator that memory loss is a defect that might be corrected for enhanced species efficiency. I hope He listens. 3.Now that we have six billion people on the planet competing for limited resources, I think it is time for God to rethink procreation. We are a long way from the cave when our faster, toothier and more corpulent predators liked to lunch on us. We are now at the top of the food chain and we are reproducing like rabbits. Worse, too many children are having children and too often these are unwanted. So why not separate the act of procreation from the act of lovemaking? My suggestion is that God install an on-off switch eight inches below the back of the neck of every male and female on earth. When, and only when, the couple - mature, thoughtful and compassionate - wish to produce progeny, then he must flip her switch to on and she must flip his switch. You can't do it yourself. It will be like two NORAD officers at Cheyenne Mountain ready to initiate a nuclear strike. Both must type in the proper code, insert and turn their keys simultaneously. I hope God likes this idea. Of course, I know what God will probably tell me. Likely he will describe this miraculous mechanism of evolution where someday, after eons of mutations and adaptations, we mortals will emerge with brains sufficiently robust to render artificial intelligence superfluous and we will all love our children with sufficient empathy to avoid the wars that tend to devour them. He will likely tell me to be patient and to await fulfillment of His plan in His own good time. If so, I will nod reverently in agreement and walk over to a heavenly tennis court where, hopefully, racquet and balls will be provided.

NICHOLAS GREEN ANDREWS' TIMELINE

Birth

September 26, 1854 • Tennessee-Nicholas' middle name "Green" may indicate that Lucy Green is his grandmother and that his middle name comes from his grandmother's maiden name.

Grandson William L. Andrews, Jr. said that his grandfather always told him that his initials NG stood for "No Good" Andrews. On 5-28-2006, Nicholas' gr-great grandson, Gerald Nicholas Andrews said that the GN in his name stood for Good for Nothing Andrews

Age 1 — Birth of brother James (Jones) Andrews(1856–1886)

1856

Age 4 — Birth of brother George A. Andrews(1859–1864)

January 24, 1859

Age 6 — Census

1860 • Marshall County, Tennessee -

1860 Census: Wm V. Andrews 35 Farmer, Value of Real Estate $1,700 Value of Personal Estate $1135 Tennessee Andrews 31 Housekeeper William J. Andrews 9 Nicholas G. Andrews 4 Eron A. Andrews 1 Male Susan Tanner 20 Domestic

Age 6 — Residence

1860 about • Lewisburg -When Grandpa (Nicholas) was a little boy, 6 or 7, maybe a little later, I think they lived on the edge of town up here. Actually, it was on the Old Columbia Highway I used to go… but it's right there before you get to the new high school, on the Old Columbia Hwy near the Industrial School. Nicholas lived there when he was a boy. Just when he was real young. It wasn't in town then. It was way out. I don't know if it was a farm or not, but they had some land, not a very big farm I don't think.

Age 6 — Birth of brother James Douglas (J.D. or Jimmy) Andrews(1861–1925)

July 13, 1861 • Marshall County, Tennessee

Age 9 — Birth of sister Anna McDora Andrews(1864–1937)

September 17, 1864 • Tennessee

Age 10 — Death of brother George A. Andrews(1859–1864)

November 4, 1864 • Marshall County, Tennessee

Age 12 — Death of sister Jane Andrews(1853–1866)

1866 • Marshall County, Tennessee.

Age 13 — Birth of sister Cora Lee Andrews(1868–1912)

March 1, 1868 • Tennessee

Age 13 — Birth of sister Ada P. or Peay (twin) Andrews(1868–1868)

March 1, 1868 • Marshall County, Tennessee

Age 13 — Death of sister Ada P. or Peay (twin) Andrews(1868–1868)

July 15, 1868 • Marshall County, Tennessee

Age 16 — Residence

1870 • District 16, Marshall County, Tennessee

Age 21 — Occupation

1875

Farmer

Age 23 — Marriage

October 20, 1877

Sara Elizabeth "Sallie" Bryant

(1860–1928)

Age 23 — Birth of daughter Myrtle Ada Bryant Andrews (1878–1952)

September 11, 1878 • Tennessee

Age 24 — Birth of daughter Ader M. Andrews(1879–1952)

1879 • Tennessee

Age 26 — Census

1880 • Marshall County, Tennessee

Nicademas Andrews age 24

Birth of son William Lafayette (known as W.L. or Will) Andrews Sr.(1881–1924)

August 23, 1881 • Tennessee

Age 31 — Birth of son Jones B. Andrews(1886–1886)

January 20, 1886 • Marshall County, Tennessee

Age 32 — Death of son Jones B. Andrews(1886–1886)

October 24, 1886 • Marshall County, Tennessee

Age 32 — Parents, Grandparents and First Son

1886 • My grandfather was Nicholas Green Andrews. His father, I think it was his father, William Vaughn Andrews. Now I can't think how Lucy and Jones came in there, because they [Nicholas and Sallie] named their first child Jones and I think it's in that paper I

I have though. It's in a book. Granddaughter Sara - their first child and it was a boy. It was Jones. He died as an infant from some childhood disease. We always took some flowers to the marker on his grave. You could hardly read it. A tiny little marker.

Age 32 — Death of brother James (Jones) Andrews(1856–1886)

1886 • Marshall County, Tennessee w/o issue

Age 34 — Birth of daughter Anna "Annie" Lou Andrews(1889–1970)

February 16, 1889 • Tennessee

Age 36 — Birth of son Roy Bryant Andrews(1891–1949)

January 17, 1891 • Tennessee

Age 37 — Voting Record

1891 • Marshall County, Tennessee

Incudes the Bryant family

Age 43 — Birth of son Kenneth Allen Andrews(1897–1971)

October 11, 1897 • Tennessee

Age 46 — Census

1900 • Marshall County, Tennessee

Cousin Mattie M. Dark [25 years old] living with Nicholas' family

Age 46 — Death of father William Vaughn (possibly Varney) Andrews(1824–1901)

February 22, 1901 • Marshall County, TN; buried in Cunningham Cemetery on John Lunn Road, Marshall County, Tennessee

Age 49 — Property

May 23, 1904 • Marshall County, TN – Grandson William L. Andrews: He had a car, but I don't think he drove it. Uncle Bryant did all the driving. 40 Acres conveyed by Nicholas Andrews to Jas A. Ewing.

Age 51 — Wedding of Son WL

September 1905 • the hospitable country home of Mr. and Mrs. Nick Andrews on the Franklin Pike was thrown open to forty invited guests to welcome the wife of their son, William, who arrived with his bride on the 6 o'clock train from Fairfield, Illinois, where they were

united in marriage Sunday evening September 16. At 9 o'clock an elegant menu was served. Mr. and Mrs. Andrews were the recipients of numerous and costly presents and their many friends wish them a joyous and prosperous wedded life.

Age 53 — Birth of Granddaughter Sara

June 22, 1908

William L. Andrews, Jr. - My father and mother were living at Silver Creek when she was born, but I think she was born down there (at Nicholas' farm) at that time. I don't think they were born in hospitals then I guess..

Age 54 — Death of mother Tennessee Tucker (daughter of Rachel; step-daughter of Eliz Warren Lanier)(1827–1909)

February 27, 1909 • Marshall County, Tennessee

Age 56 — Census

1910 • Berlin, Marshall County, TN - April 4, 1910, the Committee of the School House at Berlin consisted of N.G. Andrews, T.T. Hardison and F. H. Gray submitted plans to estimate on building. The Board decided to appropriate $1,000 or as much to be needed to erect a school building at the place. ---Third Row Lillian Gray --- Fifth Row, starting 4th from left, Kenneth Andrews, Bryant Andrews, Charlie Gray and Bob Gillespie.

Age 58 — Death of sister Cora Lee Andrews(1868–1912)

October 9, 1912 • Marshall County, Tennessee - Chokes Herself With a String – The vicinity of Verona was greatly shocked Wednesday when it was learned that Mrs. Cora Grey wife of Mr. Felix Grey had committed suicide.

Age 66 — Residence

1920 • Marshall, Tennessee - Carl Johnson said that Carl also said that there was a partial stone wall in back of the house that had been part of a blacksmith shop.

1920 Census - The house on his farm continued standing until lightning hit it in the late 1990s or in 2000 and it burned down leaving only the two fireplaces standing. The two fireplaces were taken down July 29, 2002.

Age 70 — Death of son William Lafayette (known as W.L. or Will) Andrews Sr.(1881–1924)

December 21, 1924 • Lewisburg, Tennessee at Doctor Wheat's hospital

Age 71 — Death of brother James Douglas (J.D. or Jimmy) Andrews(1861–1925)

November 14, 1925 • Marshall County, Tennessee

Age 73 — Death of wife Sara Elizabeth "Sallie" Bryant(1860–1928)

April 25, 1928 • Lewisburg, Marshall, Tennessee

Age 74 — Golden Wedding Anniversary

1928 • Berlin, Marshall County, Tennessee

WLA: They had their golden wedding anniversary in 1928 shortly before she died. But I remember that. We have a family reunion then. But the family all lived pretty close. That is the ones down here. My mother's people up there–they all lived pretty close.

Age 76 — Census

1930 • District 2, Marshall, Tennessee

Age 79 — Medical

July 9, 1934 • He died in the center bedroom at son WL's farm on Hwy 431 in Lewisburg at age 80. Granddaughter Martha - He had a car, but I don't think he drove it. Uncle Bryant did all the driving. He had a stroke or something when saddling Dimples. Nicholas was out here saddling up Dimples, harnessing him I should say to the buggy. He'd say, "Dimples, how many ears of corn do you want and the horse would use his hoof to scrape out the number of ears.

Age 79 — Death

July 9, 1934 • Lewisburg on son Will's farm on the Franklin Rd from Brain Hemmorage from High Blood Pressure. WLA Jr. - "he was putting the harness on, hitching Dimples to the buggy when he died of a stroke. He came up here and lived with Aunt Myrtle the last 3 or 4 years. He died in the middle bedroom. I was at school when he died, but they told me he hitched up his horse, was going to go to town. He had a buggy & a horse. He had a car, but I don't think he drove it."

Funeral

July 1934 • Lewisburg, TN – WL Andrews Sr's farm - We had the funeral on the front porch,

closed in here at the house and then I don't know if they had a funeral at a church down there, but He was actually living here at the time. He had been here a year or two, maybe three. He was living here with Aunt Myrtle.

Burial

July 10, 1934 • Andrews/Liggett Cemetery on Nicholas' farm, Marshall County, Tennessee

The family graveyard, called the Andrews/Liggett Cemetery, is on a rise on Nicholas' farm on Highway 431 (the Franklin Road) between Lewisburg and Berlin where he, his wife, his children and others in the family are buried.

Probate

1934 • Marshall County, Tennessee - WL Andrews - My grandfather died just right at the worst time of the depression. He died in 1934 but that farm sold for about $3,500.00 and then it had to be divided up. Yeah, the whole farm down there. I imagine it was close to 200 acres, I'm not sure. It's got all that land across the road that's rocky. We used to call that the Nation. Paul (Harris) and I used to play back there – get up in these big trees and then ride them down, certain kind of trees you could ride down.

Sale of Nicholas' Farm after his Death

1935 • Berlin TN -WLA My grandfather died just right at the worst time of the depression. He died in 1934 but that farm sold for about $3,500.00 and then it had to be divided up. Yeah, the whole farm down there. I imagine it was close to 200 acres, I'm not sure.

It's got all that land across the road that's rocky. We used to call that the Nation

4 Media

Children and Grandchildren

About 1999 • Martha Thompson (speaking to great-grandson John Andrews)– Well, I always thought he was partial to Bill and Sara. Well, your granddaddy was his favorite. His sister told me that. My father was the baby, but your granddad was the oldest. When asked what Nicholas was like, Martha Thompson said that he favored his son W. L. over the others and W. L., Jr. and Sara over his other grandchildren. Grandson William L. Andrews, Jr. never met any of his grandfather Nicholas' brothers and Sisters.

Home

July 29, 2002 • Grandchildren never asked whether Nicholas had built his house.

The house on his farm continued standing until lightning hit it in the late 1990s or in 2000 and it burned down leaving only the two fireplaces standing. The two fireplaces were taken down July 29, 2002.

Adoption

Grandson WLA Jr. - Palen was the adopted girl who lived with them for a while - she cooked and did things like that.

Nicholas and Slavery - Protecting Runaway Slave

Unknown • Berlin, Marshall County, Tennessee

Nicholas hid the slave Tom Tappley from the Knights of the White Camilla.

Purchase of Farm in Berlin on Franklin Pike [the Nations]

unknown • Paul (Harris) and I used to play back there – get up in these big trees and then ride them down, certain kind of trees you could ride down to the ground & then go back up. They sold the farm & divided the money. I think I got $200. He died & they sold it Uncle Bryant I think was still trying to farm down there a little bit.

Home and Furniture

Unknown • Berlin, Marshall County, Tennessee - He had a fireplace in the parlor; old houses used to have parlors –well, it was more of a company room to visit. And then the other side was a living room. There was a hall in between and two rooms upstairs, one called the "boy's upstairs" and the girls and it had different steps going up to them.

Property

Unknown • Marshall County, Tennessee -WL Andrews- My grandfather had another farm - I think he got it because somebody failed to pay it off or something- runs parallel with the highway going to Columbia, but it's over in the hills, over to the left there. He rented it out for a long time. When Bryant finally married way after my grandfather had died, he lived there.

Biography

Grandson William L. Andrews, Jr. said that his grandfather always told him that his initials NG stood for No Good Andrews. On 5-28-2006, Nicholas' gr-great grandson, Gerald Nicholas Andrews said that the GN in his name stood for Good for Nothing Andrews.

Personality

William L. Andrews, Jr. told his wife Betty that his grandfather Nicholas was the nicest man imaginable. December 13, 2008 - Elizabeth Jane Early told her son John, "Daddy told me that he loved his grandfather Nicholas more than anything."

Litigation over 60 Acres of Grandfather William Tucker

Family Graveyard

The family graveyard, called the Andrews/Liggett Cemetery, is on a rise on Nicholas' farm on Route 431 between Lewisburg and Berlin where he, his wife, his son and others in the family are buried.

Automobile

Nicholas has an automobile but I don't think he ever drove it, but his son Bryan did. He used a horse and buggy right up until his death in 1934. Nicholas' horse was named Dimples and that Nicholas would ask the horse how many ears of corn he wanted and he would scrape his hoof on the ground for the number of ears he wanted.

Family Arrival in Tennessee

Sara Josephine Andrews: "My grandfather (Nicholas) said the Andrews family in Middle Tennessee came from Virginia. Three brothers came from Virginia. One settled in Williamson County (our line), one in Davidson County, and one in Alabama (Roy Andrews line)

Siblings of Nicholas

William L. Andrews, Jr. never met any of Nicholas' brothers and Sisters.

Occupation

Berlin, Marshall County, Tennessee