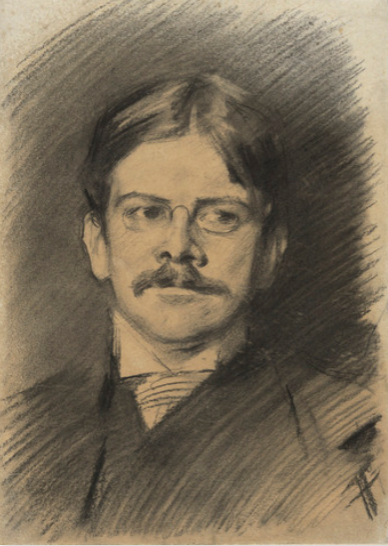

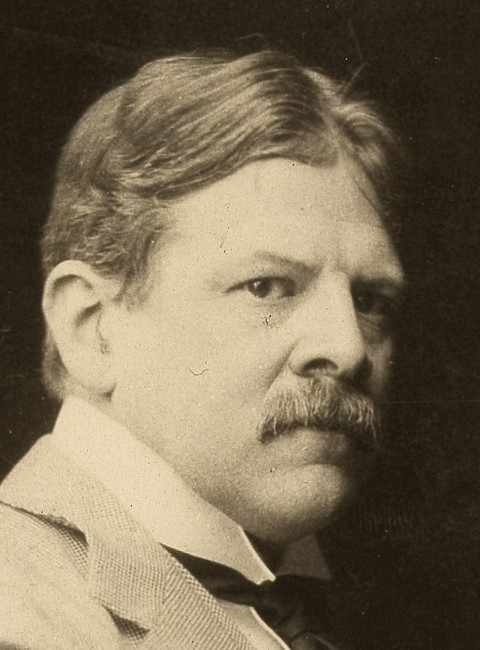

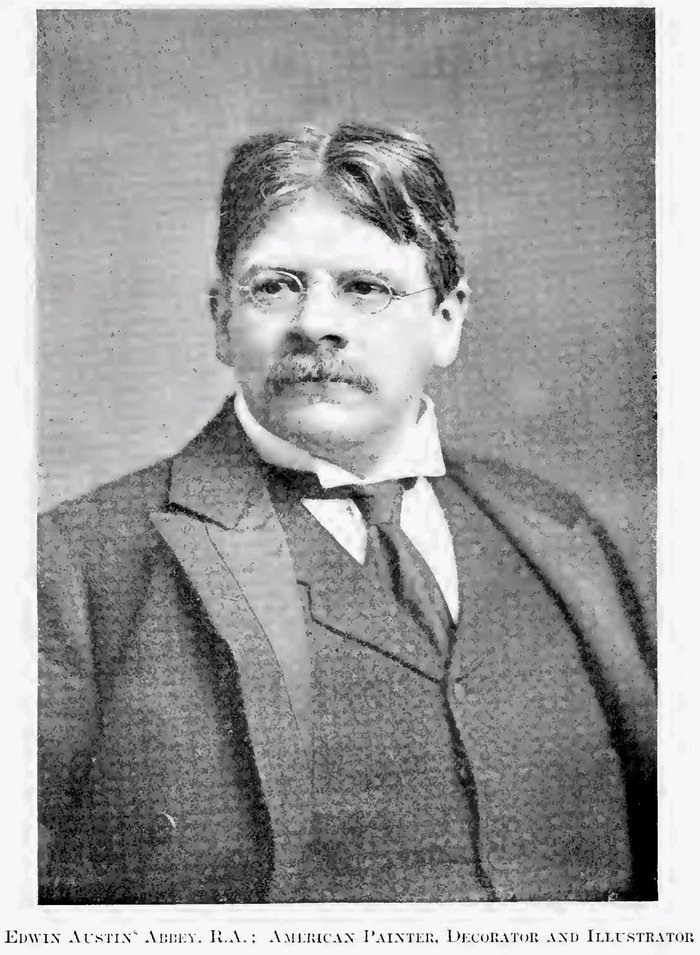

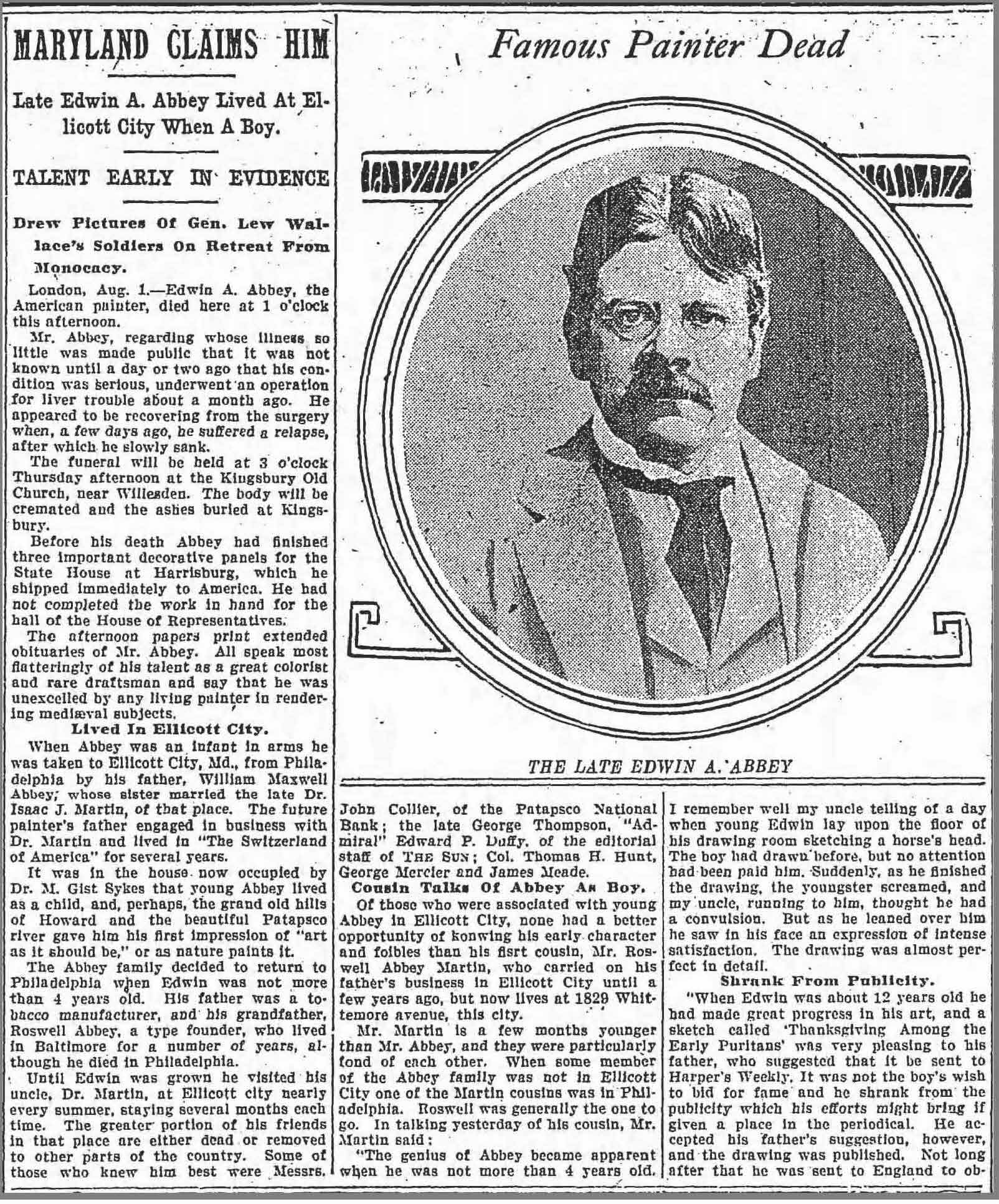

EDWIN AUSTIN ABBEY, son of William Maxwell and Margery Ann (Kiple) Abbey, born in Philadelphia, Pa., April 1, 1852; died in England, July 31, 1911.

Married in New York City, April 22, 1890, MARY GERTRUDE MEAD, born in Torquay, Devonshire, England, March 15, 1851, daughter of Frederick and Mary E. (Scribner) Mead.

She was graduated from Vassar College in 1870, studied in Berlin, 1881-2, and in Paris, 1883-4. They had no children.

The following is for the most part made up from a most appreciative article in the Craftsman of October, 1911, by Louis A. Holman :

Born in Philadelphia eight years before the Civil War broke out, Abbey was in school at the time when men's thoughts were chiefly on the great struggle. His two years' art training were over before the paralyzing effect of war had passed. He was in a very real sense a self-made man, as severe a critic of his own work and as exacting as any master could have been. He, however, always gave the credit for his success to his merchant grandfather, a man of fine artistic feeling, who like Abbey's own father spent many a day at his easel. A friend who called on Abbey while he was at work on the coronation picture has recently recalled some of the conversation. "Abbey," said the caller, "it is a great work and a great chance ; but teU me, how did you get it?" "Through my grandfather," said Abbey. "I see by the papers that you are also to decorate the new Capitol of Pennsylvania. Did your grandfather get that commission for you too?" And Abbey gravely replied : "If I do the work he will be the cause." There is a photograph of Abbey taken when he was eight years old. With dreamy unconsciousness he had posed himself at a table, not with a toy but with paper and pencil.

When he was but fourteen, it is said, "Oliver Optic's Magazine for Boys and Girls" published a rebus of his designing. He began drawing on wood for a wood engraver when he was sixteen. A sketch called "The First Thanksgiving" submitted to Harper's Magazine was accepted. This triumph eventually resulted in 1871 in his joining the staff of that magazine. In the July Harper's of 1871 there is a poem accompanied by a number of illustrations done by several of the staff. Among them is one signed by Abbey.

In 1873 he was Harper's humorous artist, and illustrated the "Editor's Drawer." In 1878 he went to England to make the Herrick illustrations, and, except for short visits, he never returned to America. Englishmen soon forgot that this genial, brilliant man was a foreigner, possibly because he was supremely happy in the land of his adoption.

He was everywhere held in high favor, and honors showered upon him. He became one of a notable group of American artists who found in England a sympathetic artistic environment. Abbey materially aided in increasing the esteem in which his fellow countrymen were held. There is a story that once he tried to break away from the witchery of the picturesque country of England, but after his household goods had reached America he weakened and the unpacking was not done until they got back to England.

At Broadway in Worcestershire, Abbey found friends and there he lingered, gathering material for his drawings. A friend of his said that in the wonderful garden of Russell House, the home of Frank Millet, he had often seen, on the same morning, each painting from his own model. Abbey, Sargent, Miller, Alma-Tadema and Alfred Parsons. It was at hospitable Russell House that Abbey first met Miss Mary Gertrude Mead of New York, who later became his wife. Here, too, he had the good fortune to meet Alfred Parsons, and Alfred Parsons had the still better fortune to meet Abbey. Then and there began that wonderful collaboration, the result of which for many a year charmed the artistic world.

Successful, from every point of view, as were the illustrations for Herrick, and Goldsmith, and Shakespeare, he yet longed to be a beginner in other fields of art, not that he Edwin might make a fortune or win applause, but that he might have the joy of wandering in a new region. He bought an ancient house at Fairford, Gloucestershire, some fifty miles south of Broadway. Here he built a large studio and entered the lists as a painter of English romance and history.

In 1891 he began the famous "Holy Grail," a series for the Boston Public Library Five years later his "Richard, Duke of Gloucester and the Lady Anne" won him his A.R.A. In two more years he became a full Academician. The work, however, which brought him his greatest recognition in England was his painting of the coronation of Edward the Seventh, "by command" of the king. In the State Capitol at Harrisburg, Pa., are eight murals, of such widely different character, being wholly symbolic subjects

treated in a modern manner, that he was compelled to leave the well-worn road and blaze out a new one.

He had essayed work in one province after another : illustration ; pen and wash drawings ; paintings, water color, pastel and oil ; mural decoration, historic and symbolic.

He will hold his place as one of America's foremost colorists, as one of her rarest draftsmen, as the most poetic painter of mediaeval subjects in his time, and as the greatest illustrator that America has yet produced.

Close student and hard worker as Abbey proved himself, he found time for friends and for play. There probably never lived an American artist who had a greater host of friends. So often after his death were heard the words, "Abbey was a most lovable man." He was the soul of generosity, not only in material things, but in his sketches and drawings and in the preparation and care he exercised in connection with his mural decorations. He spent much more than his compensation on models and costumes and research work that the paintings might be worthy the place they were to occupy. Artists say that when he criticised their work he always searched for something encouraging to say. He was instinctively refined, with a manner that would have won him his way into palaces even if he had started life as a hod-carrier. He never considered himself an expatriate, never lost his American accent or manner. He had a keen love for all clean, good sport, and had the devotion of an American boy for baseball. As he could not in England bring together enough men to play this game, he took up cricket as a substitute, had a ground prepared at his Gloucestershire house, and himself became president of the club.

Perhaps there was nothing about him that made such a universal appeal as his alert sense of humor. His nickname in the old New York days was "Chestnut," an appellation derived from a favorite story which he could relate in a most inimitable way. The Chestnut Story was one of those interminable, pointless, humbug narratives, eternally getting to the point and never arriving there ; exciting vast interest and calculation in regard to the chestnuts on a certain tree ; promising a rich and racy solution in the very next sentence ; straying off into episodes that baffled the ear and disappointed the hope. The tale could be prolonged by him when he was at his best for a good part of an hour, without ever releasing the attention or satisfying the expectation. English literary men began to use the title in their writing as a type of an endless or unsatisfactory yarn, and the word Chestnut, crossing the sea, returned again to the land of its birth and became the accepted definition of what is tedious, old and interminable.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

EDWIN AUSTIN ABBEY, son of William Maxwell and Margery Ann (Kiple) Abbey, born in Philadelphia, Pa., April 1, 1852; died in England, July 31, 1911.

Married in New York City, April 22, 1890, MARY GERTRUDE MEAD, born in Torquay, Devonshire, England, March 15, 1851, daughter of Frederick and Mary E. (Scribner) Mead.

She was graduated from Vassar College in 1870, studied in Berlin, 1881-2, and in Paris, 1883-4. They had no children.

The following is for the most part made up from a most appreciative article in the Craftsman of October, 1911, by Louis A. Holman :

Born in Philadelphia eight years before the Civil War broke out, Abbey was in school at the time when men's thoughts were chiefly on the great struggle. His two years' art training were over before the paralyzing effect of war had passed. He was in a very real sense a self-made man, as severe a critic of his own work and as exacting as any master could have been. He, however, always gave the credit for his success to his merchant grandfather, a man of fine artistic feeling, who like Abbey's own father spent many a day at his easel. A friend who called on Abbey while he was at work on the coronation picture has recently recalled some of the conversation. "Abbey," said the caller, "it is a great work and a great chance ; but teU me, how did you get it?" "Through my grandfather," said Abbey. "I see by the papers that you are also to decorate the new Capitol of Pennsylvania. Did your grandfather get that commission for you too?" And Abbey gravely replied : "If I do the work he will be the cause." There is a photograph of Abbey taken when he was eight years old. With dreamy unconsciousness he had posed himself at a table, not with a toy but with paper and pencil.

When he was but fourteen, it is said, "Oliver Optic's Magazine for Boys and Girls" published a rebus of his designing. He began drawing on wood for a wood engraver when he was sixteen. A sketch called "The First Thanksgiving" submitted to Harper's Magazine was accepted. This triumph eventually resulted in 1871 in his joining the staff of that magazine. In the July Harper's of 1871 there is a poem accompanied by a number of illustrations done by several of the staff. Among them is one signed by Abbey.

In 1873 he was Harper's humorous artist, and illustrated the "Editor's Drawer." In 1878 he went to England to make the Herrick illustrations, and, except for short visits, he never returned to America. Englishmen soon forgot that this genial, brilliant man was a foreigner, possibly because he was supremely happy in the land of his adoption.

He was everywhere held in high favor, and honors showered upon him. He became one of a notable group of American artists who found in England a sympathetic artistic environment. Abbey materially aided in increasing the esteem in which his fellow countrymen were held. There is a story that once he tried to break away from the witchery of the picturesque country of England, but after his household goods had reached America he weakened and the unpacking was not done until they got back to England.

At Broadway in Worcestershire, Abbey found friends and there he lingered, gathering material for his drawings. A friend of his said that in the wonderful garden of Russell House, the home of Frank Millet, he had often seen, on the same morning, each painting from his own model. Abbey, Sargent, Miller, Alma-Tadema and Alfred Parsons. It was at hospitable Russell House that Abbey first met Miss Mary Gertrude Mead of New York, who later became his wife. Here, too, he had the good fortune to meet Alfred Parsons, and Alfred Parsons had the still better fortune to meet Abbey. Then and there began that wonderful collaboration, the result of which for many a year charmed the artistic world.

Successful, from every point of view, as were the illustrations for Herrick, and Goldsmith, and Shakespeare, he yet longed to be a beginner in other fields of art, not that he Edwin might make a fortune or win applause, but that he might have the joy of wandering in a new region. He bought an ancient house at Fairford, Gloucestershire, some fifty miles south of Broadway. Here he built a large studio and entered the lists as a painter of English romance and history.

In 1891 he began the famous "Holy Grail," a series for the Boston Public Library Five years later his "Richard, Duke of Gloucester and the Lady Anne" won him his A.R.A. In two more years he became a full Academician. The work, however, which brought him his greatest recognition in England was his painting of the coronation of Edward the Seventh, "by command" of the king. In the State Capitol at Harrisburg, Pa., are eight murals, of such widely different character, being wholly symbolic subjects

treated in a modern manner, that he was compelled to leave the well-worn road and blaze out a new one.

He had essayed work in one province after another : illustration ; pen and wash drawings ; paintings, water color, pastel and oil ; mural decoration, historic and symbolic.

He will hold his place as one of America's foremost colorists, as one of her rarest draftsmen, as the most poetic painter of mediaeval subjects in his time, and as the greatest illustrator that America has yet produced.

Close student and hard worker as Abbey proved himself, he found time for friends and for play. There probably never lived an American artist who had a greater host of friends. So often after his death were heard the words, "Abbey was a most lovable man." He was the soul of generosity, not only in material things, but in his sketches and drawings and in the preparation and care he exercised in connection with his mural decorations. He spent much more than his compensation on models and costumes and research work that the paintings might be worthy the place they were to occupy. Artists say that when he criticised their work he always searched for something encouraging to say. He was instinctively refined, with a manner that would have won him his way into palaces even if he had started life as a hod-carrier. He never considered himself an expatriate, never lost his American accent or manner. He had a keen love for all clean, good sport, and had the devotion of an American boy for baseball. As he could not in England bring together enough men to play this game, he took up cricket as a substitute, had a ground prepared at his Gloucestershire house, and himself became president of the club.

Perhaps there was nothing about him that made such a universal appeal as his alert sense of humor. His nickname in the old New York days was "Chestnut," an appellation derived from a favorite story which he could relate in a most inimitable way. The Chestnut Story was one of those interminable, pointless, humbug narratives, eternally getting to the point and never arriving there ; exciting vast interest and calculation in regard to the chestnuts on a certain tree ; promising a rich and racy solution in the very next sentence ; straying off into episodes that baffled the ear and disappointed the hope. The tale could be prolonged by him when he was at his best for a good part of an hour, without ever releasing the attention or satisfying the expectation. English literary men began to use the title in their writing as a type of an endless or unsatisfactory yarn, and the word Chestnut, crossing the sea, returned again to the land of its birth and became the accepted definition of what is tedious, old and interminable.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Family Members

Sponsored by Ancestry

Advertisement

Explore more

Sponsored by Ancestry

Advertisement