Married Theodore Wilford Turley, 1 Nov 1882, St. George, Washington, Utah

Children - James Theodore Turley, Pearl Turley, Sarah Turley, Lucy Turley, Ormus Flake Turley, Lowell Barr Turley, Frederick Andrew Turley, Roberta Turley, son Turley, Harvey Isaac Turley, Harry William Turley

History - Mary Agnes Flake, the oldest daughter of William Jordan Flake and Lucy Hannah White, was born February 16, 1866, the fifth of their thirteen children. She was named for her two grandmothers. The family lived in Beaver City, Utah until the fall of 1877 when the family was called to help colonize the Arizona Territory. They were counseled to, “Sell everything you can’t take with you. Leave nothing to come back to.”

At eleven years of age, Mary was described as being a large, strong girl with snappy blue eyes and fun-loving nature. Older brothers, James and Charles, had to herd the cattle and horses on the journey, so William designated Mary as teamster of one of their wagon teams most of the way--except when she and her 7-year-old sister Jane, became desperately ill with diphtheria. That winter was bitterly cold and wet. Some days they could travel only five miles.

Mary’s father negotiated the purchase of the Stinson Ranch [Snowflake] on Silver Creek for 550 head of “Utah” cattle, to be delivered over several years time. This meant returning to Utah each year to procure more cattle; Mary made three trips back to Beaver as a young teenager. Once, driving a mule team down narrow, steep Lee’s Backbone to the ferry on the Colorado River, she lost her balance and fell, but caught the brake. Her father heard her cry out and looked back to see her hanging off the wagon over the steep descent. She called, “I’m alright father, go on!

On the Flakes’ return trip from Utah in 1878, the Isaac Turley family traveled with them, and Mary and Theodore Wilford Turley became well acquainted. Four years later, with two other young couples, they made a joyous trip to St. George, Utah to be married in the Temple on November 1, 1882, by Pres. John D. T. McAllister. What a long, happy 21-day trip each way. They were just kids—Mary, 16, and Theodore was 19—they had little formal schooling, but were well-qualified in pioneer living. They were known by family and friends as “Teed” and “Molly.”

Teed gave Molly a wedding ring he made from a 25-cent piece. A few years later when this ring broke, Mary said, “Guess I won’t have to stay with you anymore, our bargain is broken!” Going to his blacksmith shop, Teed came back with a ring made from a horseshoe nail, and putting it on Molly’s finger, said, “When this wears out I will give you permission to leave.”

Upon coming back to Snowflake as newlyweds, they cleaned out a chicken coop belonging to her brother James and began housekeeping with a stove, table, two spoons, two plates, and a bed. After living there for six months, her father gave them a lot and they built a two-room log house, and later a nice two-story brick home.

Two of their first three babies, James Theodore at one year of age, and Sarah, at nine months, died of “summer complaint” [dehydration from diarrheas], which took many babies in those days, with no way to keep foods cold. Pearl survived. Then came Lucy, in 1888, and Ormus in 1890.

Mary’s brothers, James and Charles, had the U. S. Mail contract from Holbrook to Fort Apache, with the mail conveyed in buckboards. A night station for mail carriers was built at Adair (now covered by the Fool Hollow Lake near Show Low). Theodore and Mary took care of this station for several years, providing meals and beds for drivers and passengers. They looked after the teams, kept conveyances in repair, and also kept a store to supply employees, settlers for miles around, and Apache Indians who brought in wild game, corn, and beans to trade for supplies. Their daughter Lucy wrote, “I still have a picture in my mind of Indians sleeping on the floor of our store.” Their son Lowell Barr was born April 21, 1882, at Adair.

A great sadness came into the lives of the Flake family on December 8, 1892, when Mary’s 30-year-old brother Charles was killed while he and James were attempting to arrest a murderer who came into Snowflake from New Mexico.

On Sunday morning, August 4, 1895, Molly got the children dressed and off to Sunday School. She saw Sister Mary Ramsay, the town midwife, walking toward the church and beckoning her, said, “Sr. Ramsay, I need you right now!” When the children came home, they had a new baby brother. They named him Frederick Andrew Turley.

That same year in November, Apostle Francis M. Lyman notified Theodore to prepare for a mission, giving him a year to get ready. He was advised to have $125.00 for his mission and a 2 year supply of wheat for his family. It was a disastrous year. His wheat crop failed, though there were some corn, potatoes, and hay. No job could be found that would pay cash and he was sick with La Grippe [severe flu] for three months.

In November 1896, when the time came for Theodore to leave, they had only $85.00. Snowflake gave him a farewell party and Mary recorded the 34 names and amounts that folks donated--from 25 cents to $5.00, from her father and James to the total of $49.95. Theodore was 33, and Mary was 30 years old. She had five children under the age of 12 years with Fred, the youngest, 15 months old. Two years looked like a very long time.

The only time Mary kept a journal was during Theodore’s mission. Entry: “When Theo left, there was only enough flour to make one batch of bread. The children don’t have any clothes for winter. We had corn and James offered me a thousand pounds of wheat for the corn, and I was to pay him the difference.… I have a carpet loom and hope in that way to be able to help myself… I am working in the millinery business (women wore hats in those days). I do not want to depend on a soul but my Heavenly Father. On Him, I depend for health, strength, and courage to stand the trials of a missionary wife.”

A week later she records that all the children were sick with measles. To support the family, she wove rag carpets, sewed for folks, and made hats—just anything to make a little money. Mary’s entries are happy or sad depending on Theodore’s letters. “Teed is getting along very well, he has the right Spirit with him. But O it does hurt me to think he has to lay out nights without a bed, and walk ten or more miles a day with his poor foot (it was congenitally malformed in some way) and go without food.

In the spring she started clerking “from eight in the morning until after dark” at the Flake Brothers’ store for her brother James. She recorded that when she would get home at night, “I’m tired then and don’t want to work.” Pearl (12) and Lucy (9) were so young to have the responsibility those long days caring for Ormus (7), Barr (5) and Fred, (1 ½). “But I do not see how I can get along until harvest without staying in the store. It takes all I make to keep us.”

One entry, when Molly had not received a letter from Teed for several weeks, she wrote, “If I could get hold of him I would pull out what little hair he has left on his bald head!”

Mary’s journal entries were rarely dated. “….he knew he had been blest, the back had been made to fit the burden. I sincerely pray he may have strength given him to be an instrument in the Lord’s hands….I am willing to do his part and mine at home if he will perform a noble mission.”

While Theodore was away, Mary had the foundation laid for adding two more rooms to their home and also had the bricks paid for.

August 7, 1897, she wrote: “Well I am all Broke up. Just got a letter from my Dear Hub and he is in the bed with chills and fever (malaria). He is with friends but has been in the bed for 10 days. I don’t know what to do.” Theodore arrived home around the first of September and was ill for another three months or so.

Theodore resumed farming, blacksmithing, and freighting. Mary wove hundreds of yards of carpet for townsfolk—one week 110 yards, her son Fred said.

From Fred’s writings: “Mother had a large loom. During my early youth, it seemed to be the greatest machinery ever manufactured. A push and a pull sent the cylinder racing across [the loom] with another string of rags. The warp was filled into uprights that changed places every time it was pulled. It was wonderful to me. I was the one to keep the cylinders filled with the balls of rags.”

Mary liked teenagers and her children wrote about carpet-rag sewing parties (long narrow strips of cloth, usually from old clothing, were sewn together and wound into balls), molasses taffy pulls, and ice cream in the winters when the ditches would freeze over.

Daughter Lucy wrote: “Mother was noted for her hospitable, happy and generous nature. She was full of fun and good humor. Her home was always open to the homeless. Father had five brothers come from Mexico, bare-footed and in rags, in need of help. The baby brother, two years old, lived with them until he was grown. Her [Mary’s] own mother died and she was the solace of her father and two unmarried brothers. We children hardly remember sitting down to eat with just our family. We always had boarders, relatives, or friends for meals.”

Fred wrote, “Mother was the only woman I knew who made pleasure out of freight trips. Freighting from Holbrook to the government installation in Fort Apache was the most lucrative possibility in the early days of Snowflake. Mother took a buggy and us kids along for the week trip from Snowflake to deliver this freight. She would go along with the teams until near camping time, then go on ahead and make the camping spot for the night and have supper ready by the time the wagons got there.”

He also said his mother liked fishing trips in the White Mountains in the summertime. The teenage boys and girls would ride horseback and the women and children in buggies or wagons. These were about ten-day trips. Charley Cooley raised fat cattle high in the mountains and he would butcher a fine heifer yearling and bring it to the campers.

Theodore’s farmland was being eroded away by floods in Silver Creek. Fred wrote, “In 1908, father decided to take up a homestead out on the Decker Wash [20+ miles] southwest from Snowflake. His first priority was….a permanent water well. Many homesteaders had to haul drinking water. We [the family] went out there and lived through the summer and dug three wells that had water all season.” Fred was 13 years old that summer. His job was to keep the cows and horses watered. Water had to be drawn up “hand over hand” from the well in a bucket and poured into a trough they had made by cutting and burning out a large, long pine log. They milked a lot of cows to make butter and cheese, and also had lots of horses; the job seemed endless.

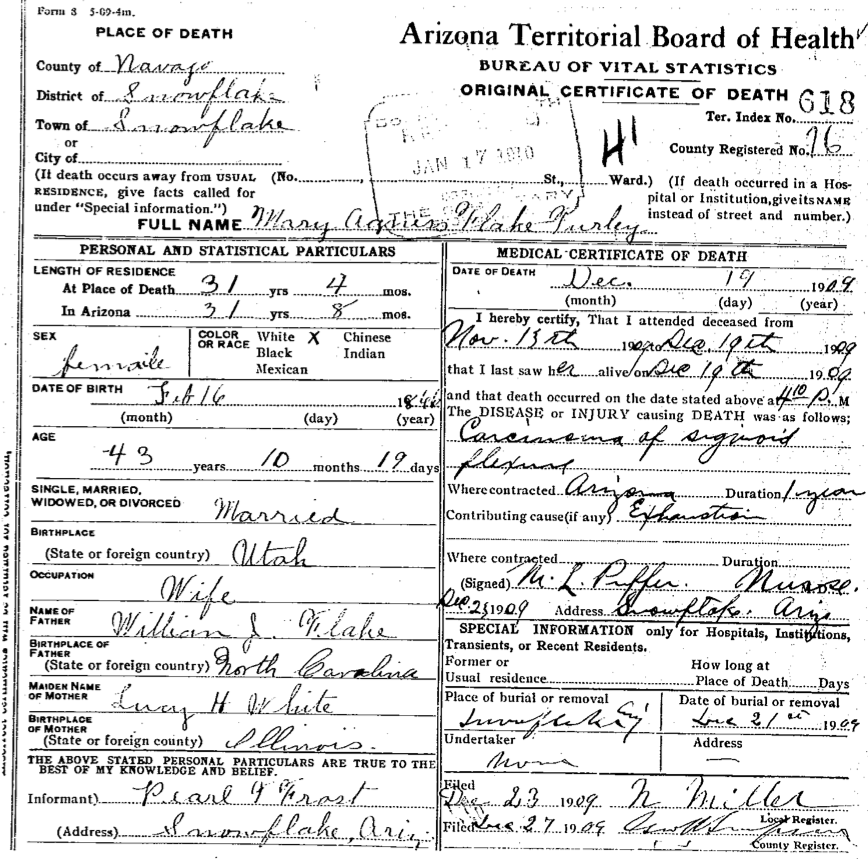

“Mother’s health became a burden the next summer. In the fall of 1909, Dr. Brown from Santa Fe determined it was terminal cancer of the stomach.”

Mary left her children a happy perspective of life, but also knowledge of the naturalness of death. Fred’s account was written November 15, 1978, when he was 83 years old: “Mother’s death was one of the most beautiful experiences of my life. Of an evening [the middle of December 1909], she said, ‘My time is soon up.’ I wish to speak with each of my children, alone. That evening Pearl, Lucy, Ormus, and Barr each spent about 30 minutes with her. The next evening myself, Roberta, Harvey, and Harry had a fine visit with mother, who was nearly free from pain.

The next morning mother said, ‘Well, this is my last day. They are coming for me.’ Besides the family, Uncle Jim [Flake] and Aunt Belle [Flake, Charles’ widow] were present. All seemed to be pleasant while spending several minutes in just family conversation.

Suddenly Mother looked directly up into the corner of the room and said, ‘They are coming for me. Jim, I will be seeing Nancy [his wife who had died, leaving 9 young children] in just a few minutes. Please give me a special message for her. I can tell all about you and the family, but just a personal message from you.’ Uncle James knelt down by the bed and spent a few seconds whispering to her. Then she said, ‘Belle, give me a message for Charley [her husband killed by an outlaw in 1892].’ Aunt Belle spent a short time in real confidence. Then mother looked again at the corner of the room and said, ‘Here they come for me, you children each kisses me.’ This we did, the Father knelt, whispering for a few seconds. Mother said ‘Goodbye, darling. I’ll be waiting for you.’ She just smiled and stopped breathing.” It was December 19, 1909; Mary was 43 years old.

Twins Harvey and Harry were 4 years old; Roberta, 10; Fred, 14; Barr, 17; Ormus, 19; Lucy (21); and Pearl (24) was married to Allen Frost.

Married Theodore Wilford Turley, 1 Nov 1882, St. George, Washington, Utah

Children - James Theodore Turley, Pearl Turley, Sarah Turley, Lucy Turley, Ormus Flake Turley, Lowell Barr Turley, Frederick Andrew Turley, Roberta Turley, son Turley, Harvey Isaac Turley, Harry William Turley

History - Mary Agnes Flake, the oldest daughter of William Jordan Flake and Lucy Hannah White, was born February 16, 1866, the fifth of their thirteen children. She was named for her two grandmothers. The family lived in Beaver City, Utah until the fall of 1877 when the family was called to help colonize the Arizona Territory. They were counseled to, “Sell everything you can’t take with you. Leave nothing to come back to.”

At eleven years of age, Mary was described as being a large, strong girl with snappy blue eyes and fun-loving nature. Older brothers, James and Charles, had to herd the cattle and horses on the journey, so William designated Mary as teamster of one of their wagon teams most of the way--except when she and her 7-year-old sister Jane, became desperately ill with diphtheria. That winter was bitterly cold and wet. Some days they could travel only five miles.

Mary’s father negotiated the purchase of the Stinson Ranch [Snowflake] on Silver Creek for 550 head of “Utah” cattle, to be delivered over several years time. This meant returning to Utah each year to procure more cattle; Mary made three trips back to Beaver as a young teenager. Once, driving a mule team down narrow, steep Lee’s Backbone to the ferry on the Colorado River, she lost her balance and fell, but caught the brake. Her father heard her cry out and looked back to see her hanging off the wagon over the steep descent. She called, “I’m alright father, go on!

On the Flakes’ return trip from Utah in 1878, the Isaac Turley family traveled with them, and Mary and Theodore Wilford Turley became well acquainted. Four years later, with two other young couples, they made a joyous trip to St. George, Utah to be married in the Temple on November 1, 1882, by Pres. John D. T. McAllister. What a long, happy 21-day trip each way. They were just kids—Mary, 16, and Theodore was 19—they had little formal schooling, but were well-qualified in pioneer living. They were known by family and friends as “Teed” and “Molly.”

Teed gave Molly a wedding ring he made from a 25-cent piece. A few years later when this ring broke, Mary said, “Guess I won’t have to stay with you anymore, our bargain is broken!” Going to his blacksmith shop, Teed came back with a ring made from a horseshoe nail, and putting it on Molly’s finger, said, “When this wears out I will give you permission to leave.”

Upon coming back to Snowflake as newlyweds, they cleaned out a chicken coop belonging to her brother James and began housekeeping with a stove, table, two spoons, two plates, and a bed. After living there for six months, her father gave them a lot and they built a two-room log house, and later a nice two-story brick home.

Two of their first three babies, James Theodore at one year of age, and Sarah, at nine months, died of “summer complaint” [dehydration from diarrheas], which took many babies in those days, with no way to keep foods cold. Pearl survived. Then came Lucy, in 1888, and Ormus in 1890.

Mary’s brothers, James and Charles, had the U. S. Mail contract from Holbrook to Fort Apache, with the mail conveyed in buckboards. A night station for mail carriers was built at Adair (now covered by the Fool Hollow Lake near Show Low). Theodore and Mary took care of this station for several years, providing meals and beds for drivers and passengers. They looked after the teams, kept conveyances in repair, and also kept a store to supply employees, settlers for miles around, and Apache Indians who brought in wild game, corn, and beans to trade for supplies. Their daughter Lucy wrote, “I still have a picture in my mind of Indians sleeping on the floor of our store.” Their son Lowell Barr was born April 21, 1882, at Adair.

A great sadness came into the lives of the Flake family on December 8, 1892, when Mary’s 30-year-old brother Charles was killed while he and James were attempting to arrest a murderer who came into Snowflake from New Mexico.

On Sunday morning, August 4, 1895, Molly got the children dressed and off to Sunday School. She saw Sister Mary Ramsay, the town midwife, walking toward the church and beckoning her, said, “Sr. Ramsay, I need you right now!” When the children came home, they had a new baby brother. They named him Frederick Andrew Turley.

That same year in November, Apostle Francis M. Lyman notified Theodore to prepare for a mission, giving him a year to get ready. He was advised to have $125.00 for his mission and a 2 year supply of wheat for his family. It was a disastrous year. His wheat crop failed, though there were some corn, potatoes, and hay. No job could be found that would pay cash and he was sick with La Grippe [severe flu] for three months.

In November 1896, when the time came for Theodore to leave, they had only $85.00. Snowflake gave him a farewell party and Mary recorded the 34 names and amounts that folks donated--from 25 cents to $5.00, from her father and James to the total of $49.95. Theodore was 33, and Mary was 30 years old. She had five children under the age of 12 years with Fred, the youngest, 15 months old. Two years looked like a very long time.

The only time Mary kept a journal was during Theodore’s mission. Entry: “When Theo left, there was only enough flour to make one batch of bread. The children don’t have any clothes for winter. We had corn and James offered me a thousand pounds of wheat for the corn, and I was to pay him the difference.… I have a carpet loom and hope in that way to be able to help myself… I am working in the millinery business (women wore hats in those days). I do not want to depend on a soul but my Heavenly Father. On Him, I depend for health, strength, and courage to stand the trials of a missionary wife.”

A week later she records that all the children were sick with measles. To support the family, she wove rag carpets, sewed for folks, and made hats—just anything to make a little money. Mary’s entries are happy or sad depending on Theodore’s letters. “Teed is getting along very well, he has the right Spirit with him. But O it does hurt me to think he has to lay out nights without a bed, and walk ten or more miles a day with his poor foot (it was congenitally malformed in some way) and go without food.

In the spring she started clerking “from eight in the morning until after dark” at the Flake Brothers’ store for her brother James. She recorded that when she would get home at night, “I’m tired then and don’t want to work.” Pearl (12) and Lucy (9) were so young to have the responsibility those long days caring for Ormus (7), Barr (5) and Fred, (1 ½). “But I do not see how I can get along until harvest without staying in the store. It takes all I make to keep us.”

One entry, when Molly had not received a letter from Teed for several weeks, she wrote, “If I could get hold of him I would pull out what little hair he has left on his bald head!”

Mary’s journal entries were rarely dated. “….he knew he had been blest, the back had been made to fit the burden. I sincerely pray he may have strength given him to be an instrument in the Lord’s hands….I am willing to do his part and mine at home if he will perform a noble mission.”

While Theodore was away, Mary had the foundation laid for adding two more rooms to their home and also had the bricks paid for.

August 7, 1897, she wrote: “Well I am all Broke up. Just got a letter from my Dear Hub and he is in the bed with chills and fever (malaria). He is with friends but has been in the bed for 10 days. I don’t know what to do.” Theodore arrived home around the first of September and was ill for another three months or so.

Theodore resumed farming, blacksmithing, and freighting. Mary wove hundreds of yards of carpet for townsfolk—one week 110 yards, her son Fred said.

From Fred’s writings: “Mother had a large loom. During my early youth, it seemed to be the greatest machinery ever manufactured. A push and a pull sent the cylinder racing across [the loom] with another string of rags. The warp was filled into uprights that changed places every time it was pulled. It was wonderful to me. I was the one to keep the cylinders filled with the balls of rags.”

Mary liked teenagers and her children wrote about carpet-rag sewing parties (long narrow strips of cloth, usually from old clothing, were sewn together and wound into balls), molasses taffy pulls, and ice cream in the winters when the ditches would freeze over.

Daughter Lucy wrote: “Mother was noted for her hospitable, happy and generous nature. She was full of fun and good humor. Her home was always open to the homeless. Father had five brothers come from Mexico, bare-footed and in rags, in need of help. The baby brother, two years old, lived with them until he was grown. Her [Mary’s] own mother died and she was the solace of her father and two unmarried brothers. We children hardly remember sitting down to eat with just our family. We always had boarders, relatives, or friends for meals.”

Fred wrote, “Mother was the only woman I knew who made pleasure out of freight trips. Freighting from Holbrook to the government installation in Fort Apache was the most lucrative possibility in the early days of Snowflake. Mother took a buggy and us kids along for the week trip from Snowflake to deliver this freight. She would go along with the teams until near camping time, then go on ahead and make the camping spot for the night and have supper ready by the time the wagons got there.”

He also said his mother liked fishing trips in the White Mountains in the summertime. The teenage boys and girls would ride horseback and the women and children in buggies or wagons. These were about ten-day trips. Charley Cooley raised fat cattle high in the mountains and he would butcher a fine heifer yearling and bring it to the campers.

Theodore’s farmland was being eroded away by floods in Silver Creek. Fred wrote, “In 1908, father decided to take up a homestead out on the Decker Wash [20+ miles] southwest from Snowflake. His first priority was….a permanent water well. Many homesteaders had to haul drinking water. We [the family] went out there and lived through the summer and dug three wells that had water all season.” Fred was 13 years old that summer. His job was to keep the cows and horses watered. Water had to be drawn up “hand over hand” from the well in a bucket and poured into a trough they had made by cutting and burning out a large, long pine log. They milked a lot of cows to make butter and cheese, and also had lots of horses; the job seemed endless.

“Mother’s health became a burden the next summer. In the fall of 1909, Dr. Brown from Santa Fe determined it was terminal cancer of the stomach.”

Mary left her children a happy perspective of life, but also knowledge of the naturalness of death. Fred’s account was written November 15, 1978, when he was 83 years old: “Mother’s death was one of the most beautiful experiences of my life. Of an evening [the middle of December 1909], she said, ‘My time is soon up.’ I wish to speak with each of my children, alone. That evening Pearl, Lucy, Ormus, and Barr each spent about 30 minutes with her. The next evening myself, Roberta, Harvey, and Harry had a fine visit with mother, who was nearly free from pain.

The next morning mother said, ‘Well, this is my last day. They are coming for me.’ Besides the family, Uncle Jim [Flake] and Aunt Belle [Flake, Charles’ widow] were present. All seemed to be pleasant while spending several minutes in just family conversation.

Suddenly Mother looked directly up into the corner of the room and said, ‘They are coming for me. Jim, I will be seeing Nancy [his wife who had died, leaving 9 young children] in just a few minutes. Please give me a special message for her. I can tell all about you and the family, but just a personal message from you.’ Uncle James knelt down by the bed and spent a few seconds whispering to her. Then she said, ‘Belle, give me a message for Charley [her husband killed by an outlaw in 1892].’ Aunt Belle spent a short time in real confidence. Then mother looked again at the corner of the room and said, ‘Here they come for me, you children each kisses me.’ This we did, the Father knelt, whispering for a few seconds. Mother said ‘Goodbye, darling. I’ll be waiting for you.’ She just smiled and stopped breathing.” It was December 19, 1909; Mary was 43 years old.

Twins Harvey and Harry were 4 years old; Roberta, 10; Fred, 14; Barr, 17; Ormus, 19; Lucy (21); and Pearl (24) was married to Allen Frost.

Family Members

-

![]()

James Madison Flake

1859–1946

-

William Melvin Flake

1861–1861

-

![]()

Charles Love Flake

1862–1892

-

Samuel Orson Flake

1864–1864

-

![]()

Osmer Dennis Flake

1868–1958

-

![]()

Sarah Jane "Lucy" Flake Wood

1870–1952

-

![]()

George Burton Flake

1875–1878

-

![]()

Roberta Flake Clayton

1877–1981

-

![]()

Joel White Flake

1880–1977

-

![]()

John Taylor Flake

1882–1973

-

![]()

Malissa Flake

1886–1886

-

![]()

James Theodore Turley

1883–1884

-

![]()

Pearl Turley Frost

1885–1970

-

![]()

Sarah Turley

1886–1887

-

![]()

Lucy Turley Bates

1888–1983

-

![]()

Ormus Flake Turley

1890–1972

-

![]()

Lowell Barr Turley

1892–1975

-

![]()

Frederick Andrew Turley

1895–1981

-

![]()

Roberta Turley Tanner

1898–1972

-

Son Turley

1900–1900

-

![]()

Harry William Turley

1905–1944

-

![]()

Harvey Isaac Turley

1905–1995

Sponsored by Ancestry

Advertisement

Records on Ancestry

Advertisement