Fort Scott Tribune, Fort Scott, KS

September 6, 2016

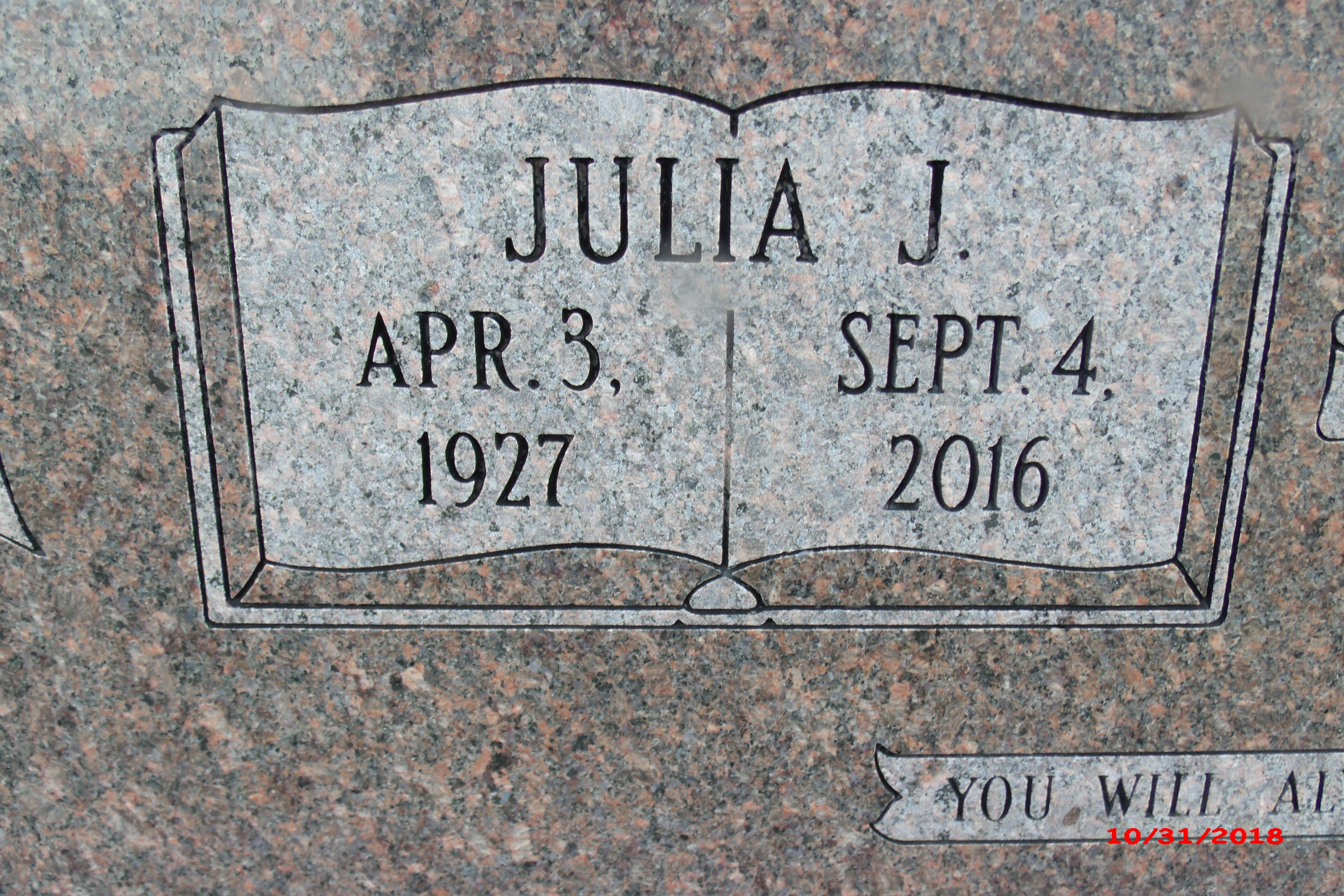

Julia June Blythe, age 89, a resident of Uniontown, Kansas died Sunday, September 4, 2016. She was born April 3, 1927, the daughter of Loren Edward and Eva Isabel Wilson Ramsey. After graduation from Uniontown High School in 1945, she was among the many women, including her Aunt Opal with whom she lived during that time, who manufactured ammunition for WW II at the Sunflower Powder Plant near DeSoto, Kansas. After that, she had earned enough money to attend cosmetology school in Kansas City, Missouri. She was working as a beautician in Fort Scott, Kansas, when she met Kaley Blythe, whom she married on New Year’s Eve, 1946. Together, they raised a family, ranched and farmed in the Uniontown area until Kaley’s death in 1991.

Julia married C. J. Blythe of Liberal, Missouri, on Valentine’s Day in 1992. He died in 2001. During their ten years together, six new grandchildren were born, including a set of triplets.

She was a member of the Uniontown Baptist Church and the West Bethel Quilting Club.

Survivors include her two daughters Etta Kaylene Perkins of Coolidge, Arizona, and Terry Kay Blythe of Prescott, Kansas; her two sons Brad Kaley Blythe and wife Cheryl, and Bud Nelson Blythe and wife Lee Belle of Uniontown; eleven grandchildren, thirteen great grandchildren, her sister-in-law and friend, Alice Ramsey of Fort Scott, and many nieces and nephews. Other members of her family are Kay Blythe of Uniontown, Gary Jones of Uniontown; C.J.’s children, Colonel Mike Blythe and wife Carol of Haymaker, Virginia, Dr. Stephen Blythe and wife Constance of Maine, and Ann Murgole and husband Joseph of Houston, Texas; and her beloved friend Elbert Turner of Fort Scott,.

She was preceded in death by her parents, her brother Ed Leon Ramsey, her two sisters Edna Lavon Miller and Nancy Lorraine Loveall, and niece, Lavon.

Following cremation, Rev. Marty DeWitt will conduct graveside services at 11:00 A. M. Wednesday, September 7th at the Uniontown Cemetery. Services are under the direction of the Cheney Witt Chapel.

********************

A LITTLE ABOUT JULIA JUNE RAMSEY BLYTHE

Author, Daughter Terry Blythe

Choose your fondest image of Julia Blythe to hold in your heart. Remember: she was not always a frail old woman.

She was the blond-haired child, the oldest, born in 1927 on a wooded hillside we can see from here, just a little south and west of Ramsey’s Ford on the Marmaton River. Already her family’s roots were many generations deep in west Bourbon County. Two years after her birth, the longest, deepest and most widespread economic depression—the Great Depression—would color her entire youth. Looking back, she could speak about the prosperity of her family. Like most others: Nobody had anything. And, like most other children, she didn’t realize their poverty. Everybody else was poor, too.

So she was a child growing up in the Dirty Thirties. She remembered those years: how her parents moved to Colorado for a better life. She started first grade there. She remembered the little black and white pony she, Ed and Edna would ride. She remembered the dust storms, and how her mother would drape wet sheets over the bedposts to prevent the children from breathing dirt. She remembered dust coating the floors, the windowsills, the dishes on the table. She remembered her brother “Sunny” doing exactly what he’d been told not to: climbing the windmill. He went all the way up. She watched her mother—who was deathly afraid of heights—climb to the top, wrap him under one arm and climb back down. She grew up watching strong parents

struggle to provide for their family. They went broke in

Colorado and moved home—back to Uniontown and Bourbon County where she would live the rest of her life, where she would live long enough to see her own children’s children buy property and start families in this place of rolling hills and fields and pastures—on this land that she and Kaley would come to characterize as a place where you’d fight the brush your whole life.

Living back home after Colorado, she, Ed and Edna walked to school, of course, taking the cows to pasture when they left of a morning and driving them home after school. They lived in essentially a two-room house at the bottom of the hill, just south of what we now call Rosie’s Cabin. She loved playing outdoor games: pop the whip, hopscotch, tag, hide-and-seek—games that required energy and not money. In high school she was a vibrant, beautiful young woman—an average student who played basketball and was Elbert Turner’s high-school sweet heart. Of course, all the boys rushed off to WW II after graduation. Like most other young women, she immediately joined the work force.

When she worked at the Sunflower Powder Plant, she lived for free with her Aunt Opal and Uncle Wayne in a garage they had rented. Sheets were used to separate sleeping areas from the rest of the “house.” As did about everybody who worked at the Sunflower Plant, she suffered headaches every night from the gunpowder used for the small arms, cannons, and rockets they constructed. But it was worth it: she saved money. She worked there until the work ran out because the war ended. Then, without knowing a single soul, she rode the train to Kansas City for cosmetology school. Through a relative who knew of somebody who knew of somebody, she acquired free room and board in exchange for being housekeeper and nanny for a family who lived in a beautiful home on the Plaza. Each morning, she boarded a city bus for the daily ride to downtown Kansas City and cosmetology school. She would laugh telling the story of her friend Betty coming to visit her, how she stepped off the city bus they were riding only discover that Betty, who was looking out the window at her with a horror stricken face, was still on the bus, now rumbling down the street. So she ran alongside the bus yelling to Betty “pull the string, pull the string,” but Betty didn’t know whatthat meant, didn’t know pulling the string rang a little bell by the driver to tell him someone wanted off. Julia chased the bus to its next stop to get her off the bus. Betty wasn’t her only visitor, though, during those months of cosmetology schooling. Her father, Granddad Ramsey, who sometimes hauled cattle to the Kansas City Stockyards, drove his cattle truck laden with plenty of fresh manure from the cattle he’d just unloaded,from the Stockyards all the way through the Plaza to come see his daughter.

After graduation, when she was a working beautician in Fort Scott, Roy Clark introduced her to one of his co-workers: Kaley Blythe. In her own words, they “fell passionately in love.”

Most of you gathered here know a lot about the rest of her life. You know she was a hard worker. You know she had a strong will. Maybe you don’t know that Julia and Kaley went broke once and prepared to give up farming. But, Doc Holt at Union State Bank would not hear of that: he believed in them and put them back in operation. Most of the now “old folks” around here remember when they bought the ranch—most thought they were crazy. But Kaley had grown up in the Flint Hills, and that ranch was the “Flint Hill” land of his dreams. He said he was lucky: He’d always known what he wanted to do: farm and ranch—and he was quite lucky in another way, too: Julia was truly a helpmate. Together, they raised a family and worked the land. She drove tractors that pulled, for example, a disc or plow. She drove grain trucks. She helped work cattle. She helped pull baby calves, making sure Kaley “pulled” when the cow “pushed.” Some remember the lunches she delivered to hay crews— a lunch that sometimes included homemade ice cream. And she still found time to sew her daughters’ clothing and patch until they couldn’t be patched any more, her husband and sons’ work clothes. She found time to cut her family and friends’ hair and give them permanents and help them put up wallpaper. And, she sometimes found time to talk to Aunt Alice for what seemed like hours on the telephone with a cup of coffee in her hand.

You know she loved taking care of her yard, her flower beds, her garden and her strawberry patch that was as big as some people’s gardens. You know she loved to crochet and quilt and how she treasured quilting with Ruth Wilson,

Kathryn Roof, Irene Stockstill, and others at West Bethel. Her final quilting projects were completed with her granddaughter Katie, whom she taught to quilt, and with whom she’d drive to Ruth Wilson’s, sometimes for advice and sometimes to share their latest project.

She wanted a graveside service, short and sweet. So, one final “you know” and that is what will never be forgotten by some of us: how she was for her family, whether in good health or bad—always—a caregiver. And, in times of sickness, the kind who would not leave your bedside. She was Julia June Ramsey Blythe and what she gave the most of was her love.

Some of her ashes will join those of her brother on that hillside near the river where she was born.

LET’S SING “SHALL WE GATHER AT THE RIVER.”

Fort Scott Tribune, Fort Scott, KS

September 6, 2016

Julia June Blythe, age 89, a resident of Uniontown, Kansas died Sunday, September 4, 2016. She was born April 3, 1927, the daughter of Loren Edward and Eva Isabel Wilson Ramsey. After graduation from Uniontown High School in 1945, she was among the many women, including her Aunt Opal with whom she lived during that time, who manufactured ammunition for WW II at the Sunflower Powder Plant near DeSoto, Kansas. After that, she had earned enough money to attend cosmetology school in Kansas City, Missouri. She was working as a beautician in Fort Scott, Kansas, when she met Kaley Blythe, whom she married on New Year’s Eve, 1946. Together, they raised a family, ranched and farmed in the Uniontown area until Kaley’s death in 1991.

Julia married C. J. Blythe of Liberal, Missouri, on Valentine’s Day in 1992. He died in 2001. During their ten years together, six new grandchildren were born, including a set of triplets.

She was a member of the Uniontown Baptist Church and the West Bethel Quilting Club.

Survivors include her two daughters Etta Kaylene Perkins of Coolidge, Arizona, and Terry Kay Blythe of Prescott, Kansas; her two sons Brad Kaley Blythe and wife Cheryl, and Bud Nelson Blythe and wife Lee Belle of Uniontown; eleven grandchildren, thirteen great grandchildren, her sister-in-law and friend, Alice Ramsey of Fort Scott, and many nieces and nephews. Other members of her family are Kay Blythe of Uniontown, Gary Jones of Uniontown; C.J.’s children, Colonel Mike Blythe and wife Carol of Haymaker, Virginia, Dr. Stephen Blythe and wife Constance of Maine, and Ann Murgole and husband Joseph of Houston, Texas; and her beloved friend Elbert Turner of Fort Scott,.

She was preceded in death by her parents, her brother Ed Leon Ramsey, her two sisters Edna Lavon Miller and Nancy Lorraine Loveall, and niece, Lavon.

Following cremation, Rev. Marty DeWitt will conduct graveside services at 11:00 A. M. Wednesday, September 7th at the Uniontown Cemetery. Services are under the direction of the Cheney Witt Chapel.

********************

A LITTLE ABOUT JULIA JUNE RAMSEY BLYTHE

Author, Daughter Terry Blythe

Choose your fondest image of Julia Blythe to hold in your heart. Remember: she was not always a frail old woman.

She was the blond-haired child, the oldest, born in 1927 on a wooded hillside we can see from here, just a little south and west of Ramsey’s Ford on the Marmaton River. Already her family’s roots were many generations deep in west Bourbon County. Two years after her birth, the longest, deepest and most widespread economic depression—the Great Depression—would color her entire youth. Looking back, she could speak about the prosperity of her family. Like most others: Nobody had anything. And, like most other children, she didn’t realize their poverty. Everybody else was poor, too.

So she was a child growing up in the Dirty Thirties. She remembered those years: how her parents moved to Colorado for a better life. She started first grade there. She remembered the little black and white pony she, Ed and Edna would ride. She remembered the dust storms, and how her mother would drape wet sheets over the bedposts to prevent the children from breathing dirt. She remembered dust coating the floors, the windowsills, the dishes on the table. She remembered her brother “Sunny” doing exactly what he’d been told not to: climbing the windmill. He went all the way up. She watched her mother—who was deathly afraid of heights—climb to the top, wrap him under one arm and climb back down. She grew up watching strong parents

struggle to provide for their family. They went broke in

Colorado and moved home—back to Uniontown and Bourbon County where she would live the rest of her life, where she would live long enough to see her own children’s children buy property and start families in this place of rolling hills and fields and pastures—on this land that she and Kaley would come to characterize as a place where you’d fight the brush your whole life.

Living back home after Colorado, she, Ed and Edna walked to school, of course, taking the cows to pasture when they left of a morning and driving them home after school. They lived in essentially a two-room house at the bottom of the hill, just south of what we now call Rosie’s Cabin. She loved playing outdoor games: pop the whip, hopscotch, tag, hide-and-seek—games that required energy and not money. In high school she was a vibrant, beautiful young woman—an average student who played basketball and was Elbert Turner’s high-school sweet heart. Of course, all the boys rushed off to WW II after graduation. Like most other young women, she immediately joined the work force.

When she worked at the Sunflower Powder Plant, she lived for free with her Aunt Opal and Uncle Wayne in a garage they had rented. Sheets were used to separate sleeping areas from the rest of the “house.” As did about everybody who worked at the Sunflower Plant, she suffered headaches every night from the gunpowder used for the small arms, cannons, and rockets they constructed. But it was worth it: she saved money. She worked there until the work ran out because the war ended. Then, without knowing a single soul, she rode the train to Kansas City for cosmetology school. Through a relative who knew of somebody who knew of somebody, she acquired free room and board in exchange for being housekeeper and nanny for a family who lived in a beautiful home on the Plaza. Each morning, she boarded a city bus for the daily ride to downtown Kansas City and cosmetology school. She would laugh telling the story of her friend Betty coming to visit her, how she stepped off the city bus they were riding only discover that Betty, who was looking out the window at her with a horror stricken face, was still on the bus, now rumbling down the street. So she ran alongside the bus yelling to Betty “pull the string, pull the string,” but Betty didn’t know whatthat meant, didn’t know pulling the string rang a little bell by the driver to tell him someone wanted off. Julia chased the bus to its next stop to get her off the bus. Betty wasn’t her only visitor, though, during those months of cosmetology schooling. Her father, Granddad Ramsey, who sometimes hauled cattle to the Kansas City Stockyards, drove his cattle truck laden with plenty of fresh manure from the cattle he’d just unloaded,from the Stockyards all the way through the Plaza to come see his daughter.

After graduation, when she was a working beautician in Fort Scott, Roy Clark introduced her to one of his co-workers: Kaley Blythe. In her own words, they “fell passionately in love.”

Most of you gathered here know a lot about the rest of her life. You know she was a hard worker. You know she had a strong will. Maybe you don’t know that Julia and Kaley went broke once and prepared to give up farming. But, Doc Holt at Union State Bank would not hear of that: he believed in them and put them back in operation. Most of the now “old folks” around here remember when they bought the ranch—most thought they were crazy. But Kaley had grown up in the Flint Hills, and that ranch was the “Flint Hill” land of his dreams. He said he was lucky: He’d always known what he wanted to do: farm and ranch—and he was quite lucky in another way, too: Julia was truly a helpmate. Together, they raised a family and worked the land. She drove tractors that pulled, for example, a disc or plow. She drove grain trucks. She helped work cattle. She helped pull baby calves, making sure Kaley “pulled” when the cow “pushed.” Some remember the lunches she delivered to hay crews— a lunch that sometimes included homemade ice cream. And she still found time to sew her daughters’ clothing and patch until they couldn’t be patched any more, her husband and sons’ work clothes. She found time to cut her family and friends’ hair and give them permanents and help them put up wallpaper. And, she sometimes found time to talk to Aunt Alice for what seemed like hours on the telephone with a cup of coffee in her hand.

You know she loved taking care of her yard, her flower beds, her garden and her strawberry patch that was as big as some people’s gardens. You know she loved to crochet and quilt and how she treasured quilting with Ruth Wilson,

Kathryn Roof, Irene Stockstill, and others at West Bethel. Her final quilting projects were completed with her granddaughter Katie, whom she taught to quilt, and with whom she’d drive to Ruth Wilson’s, sometimes for advice and sometimes to share their latest project.

She wanted a graveside service, short and sweet. So, one final “you know” and that is what will never be forgotten by some of us: how she was for her family, whether in good health or bad—always—a caregiver. And, in times of sickness, the kind who would not leave your bedside. She was Julia June Ramsey Blythe and what she gave the most of was her love.

Some of her ashes will join those of her brother on that hillside near the river where she was born.

LET’S SING “SHALL WE GATHER AT THE RIVER.”

Family Members

Sponsored by Ancestry

Advertisement

Advertisement