Margaret J. (Ray) Ringenberg, 87, died Monday, July 28, 2008 at Jesuit Retreat House in Oshkosh, WI.

Born in Fort Wayne, she was a self-employed pilot and was was a WASP during World War II. She was a member of Grabill Missionary Church, The Ninety Nines, AOPA, Experimental Aircraft Association, Air Race Classic Association, Smith Field Association, the Senior Saints and was Speaker for NASA Distinguished Lecture Series.

Survivors include daughter, Marsha J. (Stephen H.) Wright of Leo, IN; son, Michael J. Ringenberg of Leo, IN; sister, Mary F. Thompson of Indianapolis, IN; grandchildren, Jonathan (Becky) Wright, Joseph (Jen) Wright, Joshua (Kelly) Wright, Jairus Wright & Jaala Joy Wright; great-grandsons, Isaac and Owen Wright. She was preceded in death by her husband, Morris J. Ringenberg.

Service is 10 a.m. Tuesday at Grabill Missionary Church, 13637 State Street, with visitation 1 hour prior. Rev. Bill Lepley officiating. Calling also 2 to 5 and 7 to 9 p.m. Monday at the Church. Arrangements by D.O. McComb & Sons Pine Valley Park Funeral Home, 1320 E. Dupont Rd. Entombment in Covington Memorial Gardens.

Memorials to Grabill Missionary or Senior Saints.

***********************************

Published: July 29, 2008

Air pioneer Ringenberg dies

WWII pilot, 87, flew across globe

Rebecca S. Green | The Journal Gazette

Aviation pioneer and beloved local legend Margaret Ray Ringenberg, 87, died in her sleep Monday in Oshkosh, Wis.

Known around the country for her flying skills and love of aircraft, having spent nearly five years of her life in the air as a pilot, Ringenberg was in Oshkosh for an air show to give a presentation as a former member of the Women's Air Force Service Pilots, or WASPs, officials said.

And as late as last month, Ringenberg competed in the 2,312-mile women-only Air Race Classic, flying from Bozeman, Mont., to Mansfield, Mass., and finishing third, along with co-pilot Carolyn Van Newkirk, according to race results.

Ringenberg joined the WASPs in 1943 as a ferry pilot. After the WASPs disbanded, she became a flight instructor in 1945 and began racing in 1957.

Ringenberg announced the war's end in 1945 to Fort Wayne residents by dropping 56,000 leaflets proclaiming "Japan Surrenders!" from a plane over downtown. Both newspapers in the city were on strike, so a radio station hired her to make the historic "news drop."

According to her biography, Ringenberg took her first flight, from a farmer's field, at age 7. In 1998, Tom Brokaw spent an entire chapter of his best-selling book "The Greatest Generation" on Ringenberg. She gave him a flying lesson when he interviewed her.

She told him she never intended to be a pilot.

"I started out flying because I wanted to be a stewardess – you call them flight attendants nowadays – and I thought ‘what if the pilot gets sick or needs help?' I don't know the first thing about airplanes and that's where I found my challenge," Ringenberg told Brokaw. "I found it was wonderful."

On Monday, Brokaw said he was "heartbroken" to hear of her death.

"Margaret was one of my favorites," he said in a telephone interview.

Her story was so emblematic of women in particular, doing what she did well before feminism took hold, Brokaw said. And then, as did so many World War II veterans, Ringenberg went back home from the war and resumed her life.

"It touched so many people," Brokaw said of Ringenberg's story. "To do what she did, a farm girl … and then to have the life that she had."

He remembered her as someone who was completely self-effacing, with an adventurous life that went on well after the war.

Brokaw was just one of many to fly with her. Former Journal Gazette reporter Nancy Vendrely spent time with her in the air, serving as her "co-pilot" during a race in 1976.

"All I did was hold the map," Vendrely said. "It was fun to see her excellence as a pilot. She was always so calm and just sort of nonchalant about all the technical things that were involved."

Vendrely remembered Ringenberg as a humble woman, in spite of all her accomplishments and renown.

"She never talked as if she was somebody great," Vendrely said. "For her, it was just something she absolutely loved to do as long as she was able."

Roger Myers, a World War II veteran, having served as a bombardier, first met Ringenberg in 1947. The two still worked closely together on the board of the Greater Fort Wayne Aviation Museum.

Myers said at least two rooms in Ringenberg's home were filled floor-to-ceiling with trophies and ribbons from her years as a racer.

Her passion for flying took her all over the world, speaking to astronauts in Houston or at the Air Force Memorial dedication in Washington, D.C. Ringenberg seemed to speak just about anywhere from church groups to Kiwanis luncheons. In 2001, school children followed her via the Internet as she raced from England to Australia.

In July 2002, she was honored as one of Indiana's six Living Legends. In 2004, Indy Racing League driver Sarah Fisher took Ringenberg, then 82, for a spin at 150 mph around the Indianapolis Motor Speedway. Last summer, she was honored as a flying legend by the Gathering of the Eagles at the Maxwell-Gunter Air Force Base in Alabama.

She met her husband, Morris, while the two served during the war. The Ringenbergs had a son, a daughter, five grandchildren and two great-grandsons. All the grandchildren won trophies with Ringenberg, flying in races with her.

Morris and Margaret Ringenberg were married for 56 years when he died in 2003. Both were active members of Grabill Missionary Church. Her daughter, Marsha Wright, published a book about Ringenberg in 2007, "Maggie Ray, World War II Air Force Pilot."

Ringenberg wrote her own book in 1998 with Jane Roth titled "Girls Can't Be Pilots."

After going to dinner Sunday night with friends, Ringenberg, a lifetime Allen County resident, returned to a Jesuit retreat center where she was staying.

She died in her sleep, according to Shelley Donner, deputy coroner with the Winnebago County (Wis.) Coroner's Office.

Her death came as a surprise to those waiting to welcome her back to Oshkosh, said Dick Knapinski, spokesman for the Experimental Aircraft Association.

"You always feel badly when you see another of that generation pass, because of just the history that they lived through. … These and the other women like her, it is always a loss to have someone like that who meant so much to aviation and women in aviation no longer with us," Knapinski said.

"She was passionate about flying and achieving the dreams you have. A woman who was able to serve in the WASP program had to be pretty determined to start with. It was not an easy road."

That sentiment is echoed by others who knew her.

"She was just down to earth and always full of enthusiasm," Vendrely said.

"There was nothing she wasn't willing to try. She was just a small-town farm girl who had a dream, and she pursued it to the hilt."

Wright, Ringenberg's daughter, said her mother didn't talk much about being a WASP until the 50th anniversary of the war, then she started getting speaking engagements. Wright wrote all her speeches.

"She's incredibly full of energy. She pushed herself," Wright remembered.

The two had a close relationship. Ringenberg sang in choirs Wright directed, traveling around as a member of the Senior Saints.

Every Sunday the family got together for lunch, a tradition started by Ringenberg's father and continued through the generations.

"She never did like to cook, but she's willing to pick up the tab," Wright said, laughing.

When Ringenberg spoke to a group of NASA employees a few years ago, her granddaughter accompanying her, the astronauts offered her a shot at flying the space shuttle simulator – realistic down to the G-forces and the mechanical arm.

As Ringenberg played around in the cockpit, one of the instructors remarked to her granddaughter that most pilots, trained on the simulator, still crash the first few times.

Each time she tried, Ringenberg landed perfectly.

[email protected] McCartney of The Journal Gazette contributed to this story.

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

Margaret Ringenberg died in her sleep, aged 87, after a day at the Experimental Aircraft Association fly-in at Oshkosh, Wisconsin, during which she inspected new planes and met other veteran women pilots. She used to say of them: "The girls may be dragging an oxygen bottle along, but they're just as noisy as they were in world war two ... they're still that satisfied-type person." Margaret was satisfied, too. She loved to be in the air, and she had been up there all her life.

Born Margaret Ray and raised on the family farm in Indiana, she had her first ride off a nearby cornfield when she was eight, with a barnstormer who offered a flip in the air for a few cents. That planted the seed, although she did not think women were allowed to be pilots. Her post-high-school idea was to earn enough in a factory job at General Electric to study nursing, which would qualify her to be a stewardess - they were all medically trained in early passenger aviation. Then she wondered who would keep the craft in the air if an accident happened to a pilot, and told her father she wanted to learn to fly. Silence. A week later, she tried again. He explained how much it would cost and where to do it - Smith Field, Fort Wayne; once aloft, she no longer wanted to be a stewardess. She went solo at 19, and soon had her licence. After Pearl Harbor, the government sent female pilots a telegram telling them they were needed, not in combat, but to ferry planes and to teach. Her father said that he had not served, and he did not have sons, so she would be the family member on active duty.

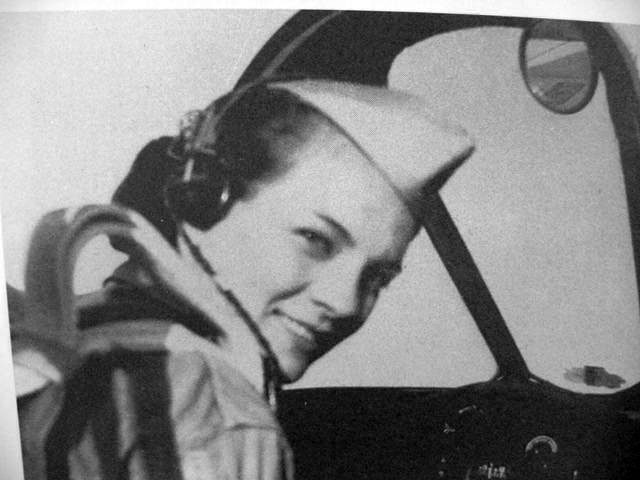

The Wasps - Women Airforce Service Pilots - did the same training as male cadets, but were not officially military; they took craft off factory production lines, test flew them, and delivered them across the US and Canada. Margaret, at 5ft 4in, was two inches too short to be first pilot on large planes - B-24, C-54, DC-3; on these, she was co-pilot. Aboard everything else, and Wasps handled more than 70 types, she was boss.

Wasps ferried seriously damaged planes to be repaired or to be cannibalised for parts. An engine blew up in Margaret's battered craft on one lonely, risky boneyard run. She was ordered to parachute clear, but she still had control of the plane and landed it safely on the nearest airfield. Wasps also towed targets for live-ammo gunnery practice; Margaret sewed targets, and her clothes, on the hangar machines.

By 1944, Wasps were no longer needed. Margaret, who was "devastated", returned home and stashed her gear in the attic. She got it out again for a parade, felt the thrill, returned to Smith Field, earned her flight instructors' rating and taught privately. She had logged the most hours at Smith but didn't have many pupils. "You know, a girl pilot wasn't real popular." So she answered phones, mowed the yard, worked in the shop, anything. When Japan was about to surrender in August 1945, she dropped 56,000 leaflets across the state announcing the end of war.

In 1946, she married a banker, Morris Ringenberg, whom she met while they were on war service. They had a son, Michael, and a daughter, Marsha (who qualified for her licence at 17, and was often co-pilot to her mother). Margaret taught a little, then in the 1950s began to race. Her success filled two rooms in the family home floor to ceiling with hundreds of trophies: she entered every Powder Puff Derby from 1957 to 1977, and every women's Air Race Classic, the Derby's successor, from 1977 to this summer, when she finished third - she was always in the top 10, and won in 1988. There were also the Grand Prix, Kentucky Air Derby, Denver Mile High and many others, and, for a lark, she flew round the world as co-pilot to a Californian doctor.

Margaret stopped counting after she had logged more than 40,000 flying hours by 1994. That year she headed a team of two other veterans in a tiny Cessna 340, the "Spirit of '76", in the Round the World Air Race. All three were members of the Ninetynines, an association started by Amelia Earhart in 1929 to change the rules that blocked lift-off to females. Their radio died mid-Atlantic, they were blown off course by a typhoon, they were tracked by F-14 jets over Iran (and had headscarves ready should they be forced to land). Everywhere they had to lower their voices to male levels to get attention from air traffic controllers. They came in last, but most-applauded.

Margaret raced from London to Sydney in 2001. She went for a spin at 180mph around the Indianapolis Motor Speedway Circuit in 2004, and, as guest of Nasa, piloted the space shuttle simulator in 2002. But she had no taste for instrument flying: at last June's classic she advised her co-pilot to "feel" take-off and listen to the pitch of cockpit gadgets.

She co-wrote her story, Girls Can't Be Pilots (1998), and her daughter told it again in Maggie Ray, WWII Air Force Pilot (2007). The honours and ovations culminated with her invitation to represent the Wasps at the dedication of the air force memorial in Washington, DC in 2006.

Morris died in 2003. Margaret's children, and five grandchildren, all of whom had been aboard as she raced, survive her.

• Margaret Ray Ringenberg, pilot, born June 17 1921; died July 28 2008

***********************************

Margaret Ray Ringenberg, who died on 28 July, 2008, was an American aviator who flew for over 60 years and wracked up more than 40,000 hours in the air, including two years in the service of her country.

She began flying during the Second World War as a member of the Women Airforce Service Pilots (WASP), flying ferry missions and test flights. She then enjoyed a long career as a commercial pilot and instructor but she was also a successful racer with more than 150 trophies to her name.

She was the subject of several books, including her own autobiography, an account of her war years by her daughter and a chapter in The Greatest Generation, Tom Brokaw's examination of American citizens who distinguished themselves during the troubled 1930s and '40s.

She was born on 17 June, 1921, in Fort Wayne, Indiana, and was obsessed with flying from an early age after seeing barnstorming exhibitions in the area. Local farmers would occasionally take her on crop dusting flights over the fields.

But despite growing up in the age of Amelia Earhart, her ambitions never stretched to being a pilot. She trained to be an air stewardess and only decided to give flying a go herself when it occurred to her that the skills might come in handy.

She told Brokaw: "I thought, 'What if the pilot gets sick or needs help? I don't know the first thing about airplanes,' and that's where I found my challenge. I never intended to solo or be a pilot. I found it was wonderful."

She began training in 1941 and flew her first solo flight at 19. Two years later she was among the 25,000 women who applied to join the WASPs, of which 1,900 were accepted and around half earned their wings. Their primary role was to ferry aircraft to various US military bases and this saw them experience air time in a wide variety of aircraft, though the experimental nature of many of these planes meant the work was often perilous.

The WASPs was never formally recognised as a military organisation andits battle for such status eventually led to the group's disbandment in 1944. Despite the 38 losses it suffered, the work of its members during the war went largely unrecognised for several decades.

Mrs Ringenberg herself was reticent about her time as a WASP and it was not until the fiftieth anniversary of the end of the war that she began to give speeches about her experiences.

By this time she was already a renowned figure in the sphere of female aviation, having been a competitor at the Powder Puff Derby race and its successor the Air Race Classic from 1957 onwards. She also took part in the Grand Prix and Denver Mile High events and at 74 she completed the Round-the-World Air Race.

Journalist Nancy Vendrely spoke of her experience co-piloting for Mrs Ringenberg in a 1976 race: "All I did was hold the map. It was fun to see her excellence as a pilot. She was always so calm and sort of nonchalant about all the technical things that were involved.

"She never talked as if she was somebody great. For her it was just something she absolutely loved to do as long as she was able."

In 1998 she published her 'aerobiography', Girls Can't Be Pilots, and this was followed in 2007 by her daughter Marsha's book Maggie Ray: World War II Air Force Pilot.

She continued to fly up until her death, competing in the 2,312-mile Air Race Classic only a month earlier and finishing a remarkable third, aged 87. She was attending an air show in Wisconsin as a special guest when she passed away in her sleep. She was married to Morris Ringenberg from 1946 to his death in 2003 and was survived by her daughter, a son and five grandchildren, many of whom had flown with her in races.

Published on the ThisIsAnnouncements.co.uk website on 29th July 2008

Margaret J. (Ray) Ringenberg, 87, died Monday, July 28, 2008 at Jesuit Retreat House in Oshkosh, WI.

Born in Fort Wayne, she was a self-employed pilot and was was a WASP during World War II. She was a member of Grabill Missionary Church, The Ninety Nines, AOPA, Experimental Aircraft Association, Air Race Classic Association, Smith Field Association, the Senior Saints and was Speaker for NASA Distinguished Lecture Series.

Survivors include daughter, Marsha J. (Stephen H.) Wright of Leo, IN; son, Michael J. Ringenberg of Leo, IN; sister, Mary F. Thompson of Indianapolis, IN; grandchildren, Jonathan (Becky) Wright, Joseph (Jen) Wright, Joshua (Kelly) Wright, Jairus Wright & Jaala Joy Wright; great-grandsons, Isaac and Owen Wright. She was preceded in death by her husband, Morris J. Ringenberg.

Service is 10 a.m. Tuesday at Grabill Missionary Church, 13637 State Street, with visitation 1 hour prior. Rev. Bill Lepley officiating. Calling also 2 to 5 and 7 to 9 p.m. Monday at the Church. Arrangements by D.O. McComb & Sons Pine Valley Park Funeral Home, 1320 E. Dupont Rd. Entombment in Covington Memorial Gardens.

Memorials to Grabill Missionary or Senior Saints.

***********************************

Published: July 29, 2008

Air pioneer Ringenberg dies

WWII pilot, 87, flew across globe

Rebecca S. Green | The Journal Gazette

Aviation pioneer and beloved local legend Margaret Ray Ringenberg, 87, died in her sleep Monday in Oshkosh, Wis.

Known around the country for her flying skills and love of aircraft, having spent nearly five years of her life in the air as a pilot, Ringenberg was in Oshkosh for an air show to give a presentation as a former member of the Women's Air Force Service Pilots, or WASPs, officials said.

And as late as last month, Ringenberg competed in the 2,312-mile women-only Air Race Classic, flying from Bozeman, Mont., to Mansfield, Mass., and finishing third, along with co-pilot Carolyn Van Newkirk, according to race results.

Ringenberg joined the WASPs in 1943 as a ferry pilot. After the WASPs disbanded, she became a flight instructor in 1945 and began racing in 1957.

Ringenberg announced the war's end in 1945 to Fort Wayne residents by dropping 56,000 leaflets proclaiming "Japan Surrenders!" from a plane over downtown. Both newspapers in the city were on strike, so a radio station hired her to make the historic "news drop."

According to her biography, Ringenberg took her first flight, from a farmer's field, at age 7. In 1998, Tom Brokaw spent an entire chapter of his best-selling book "The Greatest Generation" on Ringenberg. She gave him a flying lesson when he interviewed her.

She told him she never intended to be a pilot.

"I started out flying because I wanted to be a stewardess – you call them flight attendants nowadays – and I thought ‘what if the pilot gets sick or needs help?' I don't know the first thing about airplanes and that's where I found my challenge," Ringenberg told Brokaw. "I found it was wonderful."

On Monday, Brokaw said he was "heartbroken" to hear of her death.

"Margaret was one of my favorites," he said in a telephone interview.

Her story was so emblematic of women in particular, doing what she did well before feminism took hold, Brokaw said. And then, as did so many World War II veterans, Ringenberg went back home from the war and resumed her life.

"It touched so many people," Brokaw said of Ringenberg's story. "To do what she did, a farm girl … and then to have the life that she had."

He remembered her as someone who was completely self-effacing, with an adventurous life that went on well after the war.

Brokaw was just one of many to fly with her. Former Journal Gazette reporter Nancy Vendrely spent time with her in the air, serving as her "co-pilot" during a race in 1976.

"All I did was hold the map," Vendrely said. "It was fun to see her excellence as a pilot. She was always so calm and just sort of nonchalant about all the technical things that were involved."

Vendrely remembered Ringenberg as a humble woman, in spite of all her accomplishments and renown.

"She never talked as if she was somebody great," Vendrely said. "For her, it was just something she absolutely loved to do as long as she was able."

Roger Myers, a World War II veteran, having served as a bombardier, first met Ringenberg in 1947. The two still worked closely together on the board of the Greater Fort Wayne Aviation Museum.

Myers said at least two rooms in Ringenberg's home were filled floor-to-ceiling with trophies and ribbons from her years as a racer.

Her passion for flying took her all over the world, speaking to astronauts in Houston or at the Air Force Memorial dedication in Washington, D.C. Ringenberg seemed to speak just about anywhere from church groups to Kiwanis luncheons. In 2001, school children followed her via the Internet as she raced from England to Australia.

In July 2002, she was honored as one of Indiana's six Living Legends. In 2004, Indy Racing League driver Sarah Fisher took Ringenberg, then 82, for a spin at 150 mph around the Indianapolis Motor Speedway. Last summer, she was honored as a flying legend by the Gathering of the Eagles at the Maxwell-Gunter Air Force Base in Alabama.

She met her husband, Morris, while the two served during the war. The Ringenbergs had a son, a daughter, five grandchildren and two great-grandsons. All the grandchildren won trophies with Ringenberg, flying in races with her.

Morris and Margaret Ringenberg were married for 56 years when he died in 2003. Both were active members of Grabill Missionary Church. Her daughter, Marsha Wright, published a book about Ringenberg in 2007, "Maggie Ray, World War II Air Force Pilot."

Ringenberg wrote her own book in 1998 with Jane Roth titled "Girls Can't Be Pilots."

After going to dinner Sunday night with friends, Ringenberg, a lifetime Allen County resident, returned to a Jesuit retreat center where she was staying.

She died in her sleep, according to Shelley Donner, deputy coroner with the Winnebago County (Wis.) Coroner's Office.

Her death came as a surprise to those waiting to welcome her back to Oshkosh, said Dick Knapinski, spokesman for the Experimental Aircraft Association.

"You always feel badly when you see another of that generation pass, because of just the history that they lived through. … These and the other women like her, it is always a loss to have someone like that who meant so much to aviation and women in aviation no longer with us," Knapinski said.

"She was passionate about flying and achieving the dreams you have. A woman who was able to serve in the WASP program had to be pretty determined to start with. It was not an easy road."

That sentiment is echoed by others who knew her.

"She was just down to earth and always full of enthusiasm," Vendrely said.

"There was nothing she wasn't willing to try. She was just a small-town farm girl who had a dream, and she pursued it to the hilt."

Wright, Ringenberg's daughter, said her mother didn't talk much about being a WASP until the 50th anniversary of the war, then she started getting speaking engagements. Wright wrote all her speeches.

"She's incredibly full of energy. She pushed herself," Wright remembered.

The two had a close relationship. Ringenberg sang in choirs Wright directed, traveling around as a member of the Senior Saints.

Every Sunday the family got together for lunch, a tradition started by Ringenberg's father and continued through the generations.

"She never did like to cook, but she's willing to pick up the tab," Wright said, laughing.

When Ringenberg spoke to a group of NASA employees a few years ago, her granddaughter accompanying her, the astronauts offered her a shot at flying the space shuttle simulator – realistic down to the G-forces and the mechanical arm.

As Ringenberg played around in the cockpit, one of the instructors remarked to her granddaughter that most pilots, trained on the simulator, still crash the first few times.

Each time she tried, Ringenberg landed perfectly.

[email protected] McCartney of The Journal Gazette contributed to this story.

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

Margaret Ringenberg died in her sleep, aged 87, after a day at the Experimental Aircraft Association fly-in at Oshkosh, Wisconsin, during which she inspected new planes and met other veteran women pilots. She used to say of them: "The girls may be dragging an oxygen bottle along, but they're just as noisy as they were in world war two ... they're still that satisfied-type person." Margaret was satisfied, too. She loved to be in the air, and she had been up there all her life.

Born Margaret Ray and raised on the family farm in Indiana, she had her first ride off a nearby cornfield when she was eight, with a barnstormer who offered a flip in the air for a few cents. That planted the seed, although she did not think women were allowed to be pilots. Her post-high-school idea was to earn enough in a factory job at General Electric to study nursing, which would qualify her to be a stewardess - they were all medically trained in early passenger aviation. Then she wondered who would keep the craft in the air if an accident happened to a pilot, and told her father she wanted to learn to fly. Silence. A week later, she tried again. He explained how much it would cost and where to do it - Smith Field, Fort Wayne; once aloft, she no longer wanted to be a stewardess. She went solo at 19, and soon had her licence. After Pearl Harbor, the government sent female pilots a telegram telling them they were needed, not in combat, but to ferry planes and to teach. Her father said that he had not served, and he did not have sons, so she would be the family member on active duty.

The Wasps - Women Airforce Service Pilots - did the same training as male cadets, but were not officially military; they took craft off factory production lines, test flew them, and delivered them across the US and Canada. Margaret, at 5ft 4in, was two inches too short to be first pilot on large planes - B-24, C-54, DC-3; on these, she was co-pilot. Aboard everything else, and Wasps handled more than 70 types, she was boss.

Wasps ferried seriously damaged planes to be repaired or to be cannibalised for parts. An engine blew up in Margaret's battered craft on one lonely, risky boneyard run. She was ordered to parachute clear, but she still had control of the plane and landed it safely on the nearest airfield. Wasps also towed targets for live-ammo gunnery practice; Margaret sewed targets, and her clothes, on the hangar machines.

By 1944, Wasps were no longer needed. Margaret, who was "devastated", returned home and stashed her gear in the attic. She got it out again for a parade, felt the thrill, returned to Smith Field, earned her flight instructors' rating and taught privately. She had logged the most hours at Smith but didn't have many pupils. "You know, a girl pilot wasn't real popular." So she answered phones, mowed the yard, worked in the shop, anything. When Japan was about to surrender in August 1945, she dropped 56,000 leaflets across the state announcing the end of war.

In 1946, she married a banker, Morris Ringenberg, whom she met while they were on war service. They had a son, Michael, and a daughter, Marsha (who qualified for her licence at 17, and was often co-pilot to her mother). Margaret taught a little, then in the 1950s began to race. Her success filled two rooms in the family home floor to ceiling with hundreds of trophies: she entered every Powder Puff Derby from 1957 to 1977, and every women's Air Race Classic, the Derby's successor, from 1977 to this summer, when she finished third - she was always in the top 10, and won in 1988. There were also the Grand Prix, Kentucky Air Derby, Denver Mile High and many others, and, for a lark, she flew round the world as co-pilot to a Californian doctor.

Margaret stopped counting after she had logged more than 40,000 flying hours by 1994. That year she headed a team of two other veterans in a tiny Cessna 340, the "Spirit of '76", in the Round the World Air Race. All three were members of the Ninetynines, an association started by Amelia Earhart in 1929 to change the rules that blocked lift-off to females. Their radio died mid-Atlantic, they were blown off course by a typhoon, they were tracked by F-14 jets over Iran (and had headscarves ready should they be forced to land). Everywhere they had to lower their voices to male levels to get attention from air traffic controllers. They came in last, but most-applauded.

Margaret raced from London to Sydney in 2001. She went for a spin at 180mph around the Indianapolis Motor Speedway Circuit in 2004, and, as guest of Nasa, piloted the space shuttle simulator in 2002. But she had no taste for instrument flying: at last June's classic she advised her co-pilot to "feel" take-off and listen to the pitch of cockpit gadgets.

She co-wrote her story, Girls Can't Be Pilots (1998), and her daughter told it again in Maggie Ray, WWII Air Force Pilot (2007). The honours and ovations culminated with her invitation to represent the Wasps at the dedication of the air force memorial in Washington, DC in 2006.

Morris died in 2003. Margaret's children, and five grandchildren, all of whom had been aboard as she raced, survive her.

• Margaret Ray Ringenberg, pilot, born June 17 1921; died July 28 2008

***********************************

Margaret Ray Ringenberg, who died on 28 July, 2008, was an American aviator who flew for over 60 years and wracked up more than 40,000 hours in the air, including two years in the service of her country.

She began flying during the Second World War as a member of the Women Airforce Service Pilots (WASP), flying ferry missions and test flights. She then enjoyed a long career as a commercial pilot and instructor but she was also a successful racer with more than 150 trophies to her name.

She was the subject of several books, including her own autobiography, an account of her war years by her daughter and a chapter in The Greatest Generation, Tom Brokaw's examination of American citizens who distinguished themselves during the troubled 1930s and '40s.

She was born on 17 June, 1921, in Fort Wayne, Indiana, and was obsessed with flying from an early age after seeing barnstorming exhibitions in the area. Local farmers would occasionally take her on crop dusting flights over the fields.

But despite growing up in the age of Amelia Earhart, her ambitions never stretched to being a pilot. She trained to be an air stewardess and only decided to give flying a go herself when it occurred to her that the skills might come in handy.

She told Brokaw: "I thought, 'What if the pilot gets sick or needs help? I don't know the first thing about airplanes,' and that's where I found my challenge. I never intended to solo or be a pilot. I found it was wonderful."

She began training in 1941 and flew her first solo flight at 19. Two years later she was among the 25,000 women who applied to join the WASPs, of which 1,900 were accepted and around half earned their wings. Their primary role was to ferry aircraft to various US military bases and this saw them experience air time in a wide variety of aircraft, though the experimental nature of many of these planes meant the work was often perilous.

The WASPs was never formally recognised as a military organisation andits battle for such status eventually led to the group's disbandment in 1944. Despite the 38 losses it suffered, the work of its members during the war went largely unrecognised for several decades.

Mrs Ringenberg herself was reticent about her time as a WASP and it was not until the fiftieth anniversary of the end of the war that she began to give speeches about her experiences.

By this time she was already a renowned figure in the sphere of female aviation, having been a competitor at the Powder Puff Derby race and its successor the Air Race Classic from 1957 onwards. She also took part in the Grand Prix and Denver Mile High events and at 74 she completed the Round-the-World Air Race.

Journalist Nancy Vendrely spoke of her experience co-piloting for Mrs Ringenberg in a 1976 race: "All I did was hold the map. It was fun to see her excellence as a pilot. She was always so calm and sort of nonchalant about all the technical things that were involved.

"She never talked as if she was somebody great. For her it was just something she absolutely loved to do as long as she was able."

In 1998 she published her 'aerobiography', Girls Can't Be Pilots, and this was followed in 2007 by her daughter Marsha's book Maggie Ray: World War II Air Force Pilot.

She continued to fly up until her death, competing in the 2,312-mile Air Race Classic only a month earlier and finishing a remarkable third, aged 87. She was attending an air show in Wisconsin as a special guest when she passed away in her sleep. She was married to Morris Ringenberg from 1946 to his death in 2003 and was survived by her daughter, a son and five grandchildren, many of whom had flown with her in races.

Published on the ThisIsAnnouncements.co.uk website on 29th July 2008

Sponsored by Ancestry

Advertisement

See more Ringenberg or Ray memorials in:

- Covington Memorial Gardens Ringenberg or Ray

- Fort Wayne Ringenberg or Ray

- Allen County Ringenberg or Ray

- Indiana Ringenberg or Ray

- USA Ringenberg or Ray

- Find a Grave Ringenberg or Ray

Advertisement