In a 1773 census of Nova Scotia, the Jonathan Scott family was recorded as 1 man, 3 boys, 1 woman, and 1 girl.

In 1793, the Rev. Jonathan Scott came to Bakerstown from Yarmouth, N.S., in response to an invitationwhich has been six months in reaching him."

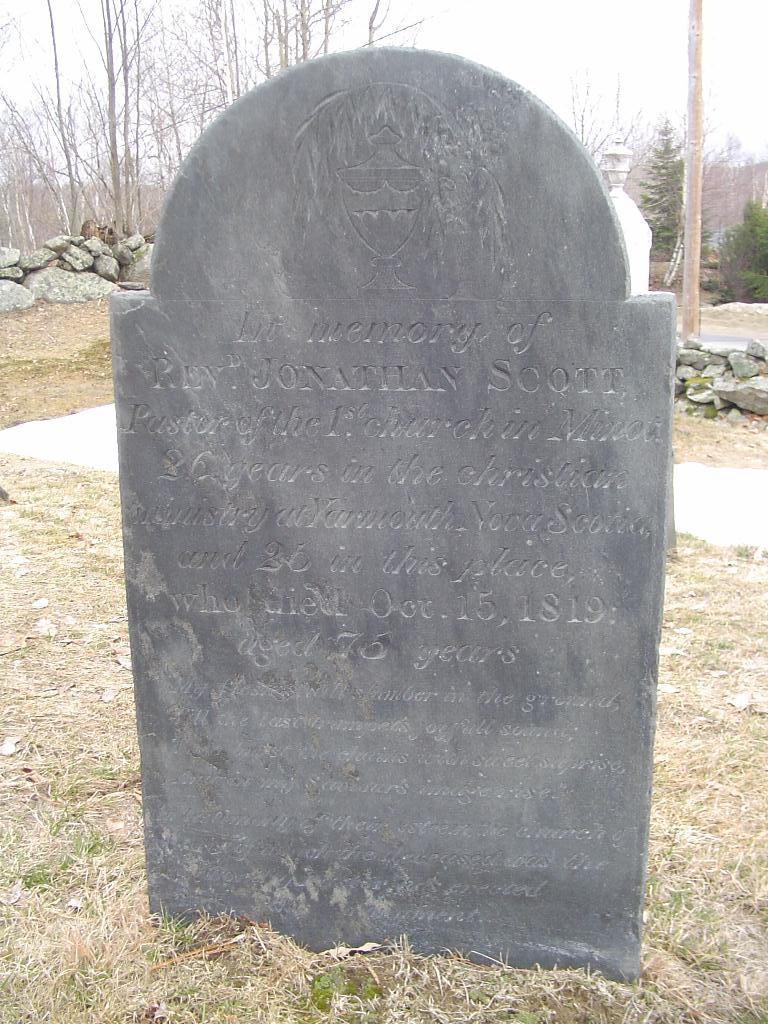

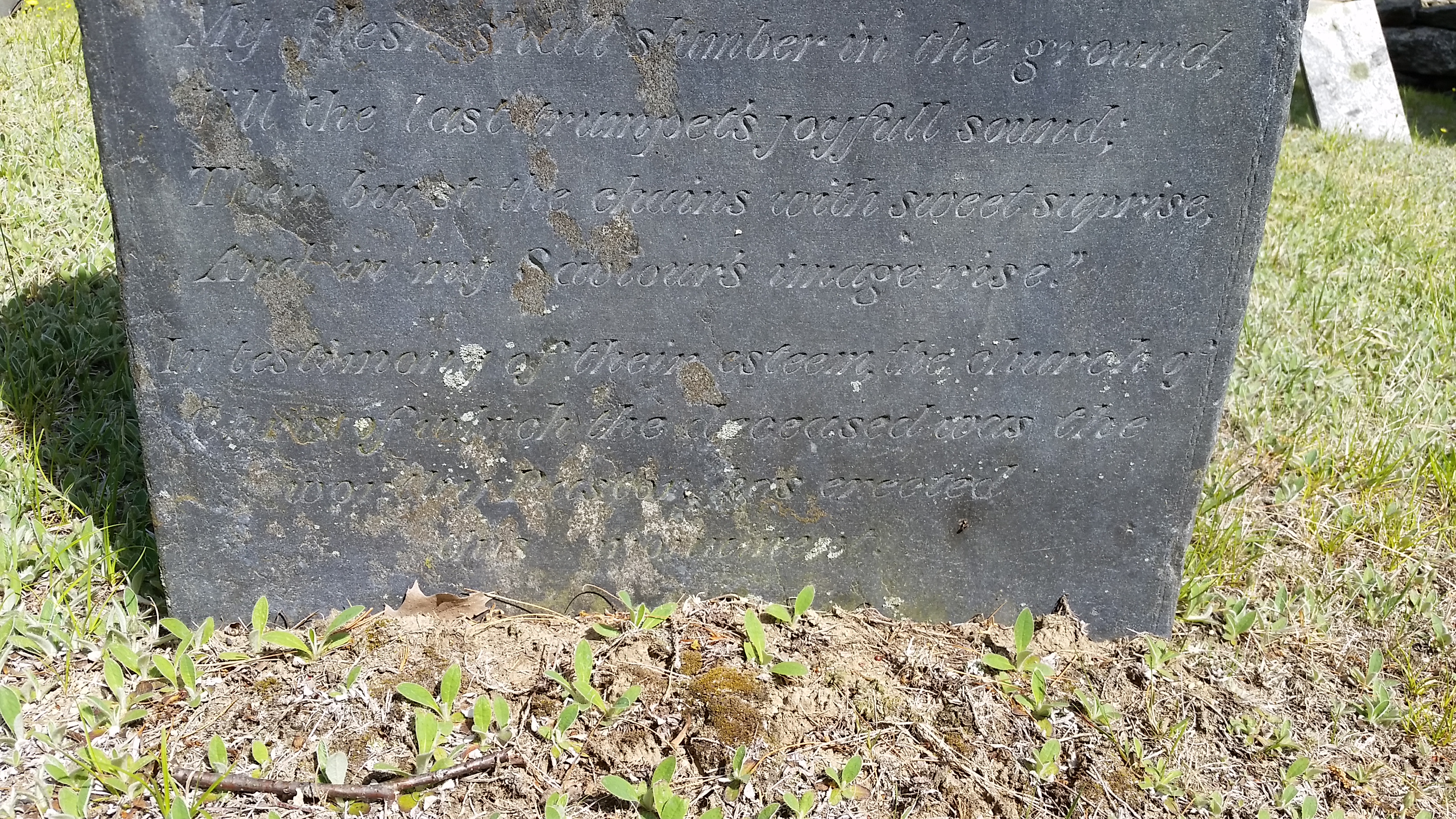

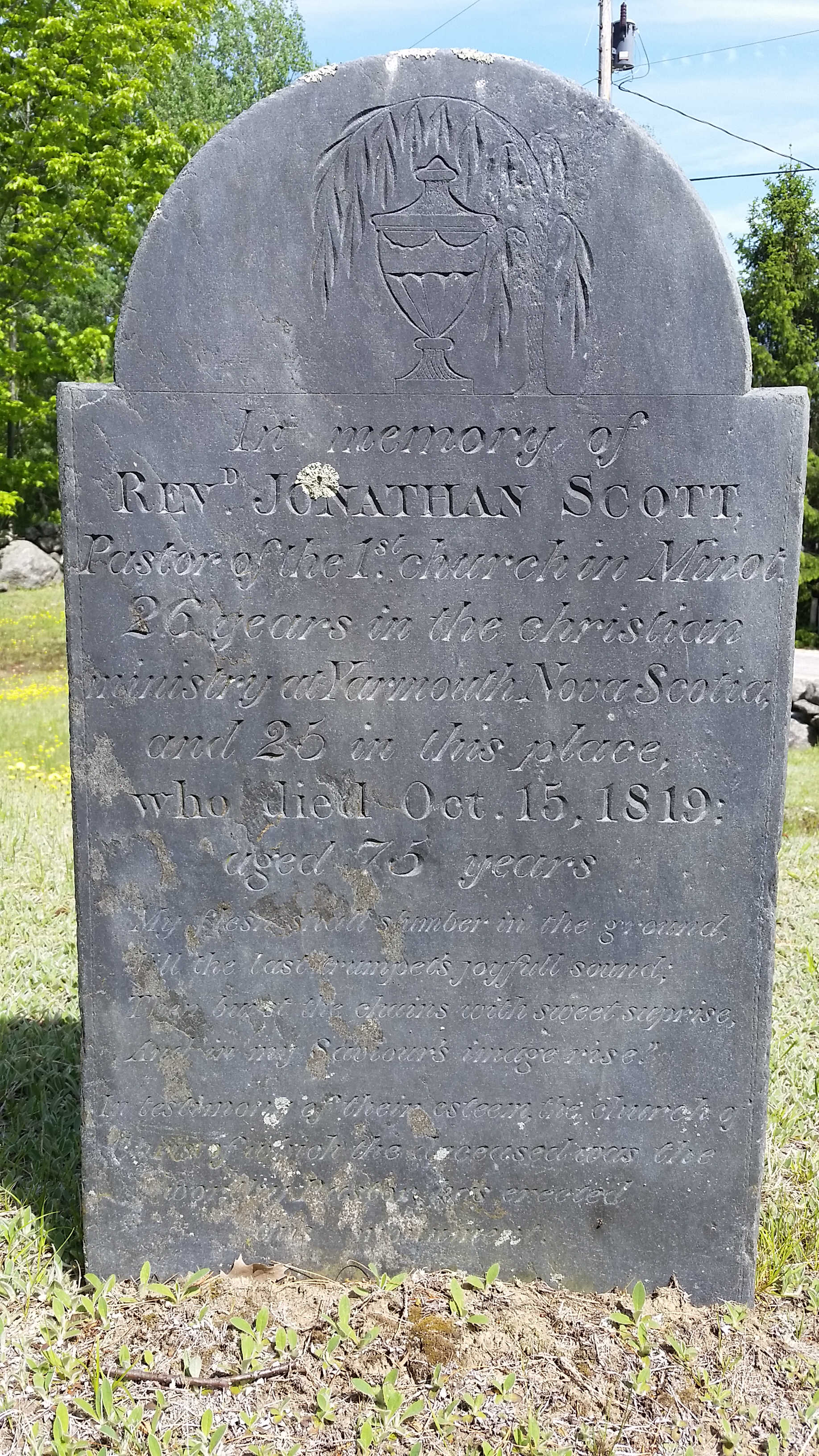

Scott, Jonathan, lay preacher, Congregational minister, and author; b. 12 Oct. 1744 in Lunenburg, Mass., seventh child of John Scott and Lydia Thwing; d. 15 Oct. 1819 in Minot (Maine).

Jonathan Scott's parents, dedicated members of the Congregational Church, taught him to read at an early age and make sure he received a strict religious upbringing based on family prayer and daily readings from the Bible. In spite of this early parental guidance, Scott did not lead a particularly pious life during his adolescent years, largely because from the age of 14 onwards he lived away from home. In 1758, two years after his father's death, Scott was apprenticed to William Goddard, a shoemaker, in Roxbury (Boston), Mass. For the next six years he was confused and unhappy "by reason of being poor, fatherless, and despised, under Servitude, and from being away from my Mother 50 miles distance." The transition was particularly disturbing because Goddard, according to Scott, "was a man of no religion; he did not pray in his house nor ask a blessing at his table; nor did he bridle his tongue from profaneness." Scott himself later confessed that while living in Roxbury he "learned to provoke God, and corrupt and dishonour man by profane and unclean language."

In April 1764, his apprenticeship completed, Scott took passage from Boston to Yarmouth, N.S., where an elder brother, Moses, had settled in the previous year. This first visit to Yarmouth was disappointing for Scott, since most of his time and hard-earned savings were spent looking after the affairs of his sick brother. Returning to Roxbury in the autumn of the same year, he went to work in the shoemaking business of his old master, Goddard. Because of personal differences, however, he soon left Goddard's employ and tried to establish his own trade. Unsuccessful in this venture, he returned to Yarmouth in April 1765. There he was able to earn a small amount of money as a fisherman, and with his savings he began putting down roots in the community. He built a log house in December 1765, and on 14 March 1768 he married Lucy Ring, the daughter of a local trader and fisherman, in a ceremony conducted by the Reverend Ebenezer Moulton*, an itinerant Baptist preacher. Later in the year the couple moved into a frame-house which Scott had built.

The year 1768 was significant in other ways for Scott. Since his childhood days he had retained a deep interest in religious matters, and in the autumn of 1768 he "began to lead in Public Worship at the desire of the people." When in 1770 he was invited to become minister he refused because of divisions within the church based on pro- and anti- evangelical positions. But after a visit by two Congregational ministers from Massachusetts, Solomon Reed and Sylvanus Conant of Middleboro, enough unity was established to encourage Scott to accept the call when it was renewed in January 1772. In March, Scott and a committee from the church traveled to Middleboro, where a council of Congregational ministers organized by Reed and Conant was to examine Scott's qualifications and suitability for the ministry. After a rigorous examination stretching over a two-week period, during which he had to preach and answer doctrinal questions put to him by the other minister, Scott was formally ordained on 28 April 1772. This was a dramatic moment in Scott's life, for here was he, a struggling farmer from a remote settlement, being approved for the ministry by a committee of well-known New England pastors, all holding degrees from Harvard or Yale. Scott was proud of this distinction and from this time on he took seriously the duty of defending the Congregational establishment against evangelical attacks. He returned to Yarmouth in May as the community's first regularly ordained Congregational minister and remained at that post until 1795, when he left to become the minister at Bakerstown (Minot, Maine).

The most interesting aspect of Scott's life during the period from 1772 to 1795 was his role in the great religious revival which swept through Nova Scotia in the 1770s, 1780s, and 1790s but which was particularly intense during the last years of the American Revolutionary War. At the height of the revival in the early 1780s Scott became the leading spokesman for those opposed to the work of Henry Alline*, the itinerant evangelical preacher. Besides visiting and corresponding with other communities throughout the colony in an effort to stem the tide of revivalism, Scott found time to write lengthy and cogent theological tracts designed to refute Alline's often peculiar religious ideas. His major work, A brief view of the religious tenets and sentiments, lately published and spread in the province of Nova Scotia, was a careful and detailed critique of Alline based on the writings of Jonathan Edwards, the famous Massachusetts minister and theologian, whose "new diversity" reconciled the evangelical position with a respect for the existing Congregational establishment. Yet in spite of such efforts, impressive for a man with no formal theological training, Scott was not successful in solidifying the anti-revivalist cause. His weighty theological critiques made scant impression on the farmers and fisherman who responded more easily to the simplistic and emotional preaching of Alline. Even in Yarmouth itself Scott lost most of his people to the revival and became in the early 1780s an embittered and isolated figure. Although he remained as the Congregational minister, his sense of failure in these years contributed to his decision to leave Yarmouth for Bakerstown in 1794.

Jonathan Scott did have his share of human frailties: he had a tendency to be short-tempered in a crisis, and the forthright manner in which he demanded increases in his salary did little to enhance his popularity during the years of the revival. On the whole, however, his failure to obtain support had less to do with his own shortcomings than with the conditions in the colony and the effectiveness of Alline's preaching. Scott was much better informed theologically than Alline, particularly in his knowledge of Jonathan Edwards's writings. He was more temperate than Alline, more reasonable, more tolerant, and more cautious in making pronouncements on complicated moral and doctrinal issues. He was also more humane in the sense that he accepted man's limitations when it came to comprehending the mysteries of God's universe. Unsure at times of his own religious condition, he was modest enough to believe that he had not found final solutions to contemporary problems. For this reason, he became somewhat out of place in the 1770s and 1780s, when simplistic preaching, emotional uplift, and a sense of certainty were the order of the day.

Gordon Stewart.

In a 1773 census of Nova Scotia, the Jonathan Scott family was recorded as 1 man, 3 boys, 1 woman, and 1 girl.

In 1793, the Rev. Jonathan Scott came to Bakerstown from Yarmouth, N.S., in response to an invitationwhich has been six months in reaching him."

Scott, Jonathan, lay preacher, Congregational minister, and author; b. 12 Oct. 1744 in Lunenburg, Mass., seventh child of John Scott and Lydia Thwing; d. 15 Oct. 1819 in Minot (Maine).

Jonathan Scott's parents, dedicated members of the Congregational Church, taught him to read at an early age and make sure he received a strict religious upbringing based on family prayer and daily readings from the Bible. In spite of this early parental guidance, Scott did not lead a particularly pious life during his adolescent years, largely because from the age of 14 onwards he lived away from home. In 1758, two years after his father's death, Scott was apprenticed to William Goddard, a shoemaker, in Roxbury (Boston), Mass. For the next six years he was confused and unhappy "by reason of being poor, fatherless, and despised, under Servitude, and from being away from my Mother 50 miles distance." The transition was particularly disturbing because Goddard, according to Scott, "was a man of no religion; he did not pray in his house nor ask a blessing at his table; nor did he bridle his tongue from profaneness." Scott himself later confessed that while living in Roxbury he "learned to provoke God, and corrupt and dishonour man by profane and unclean language."

In April 1764, his apprenticeship completed, Scott took passage from Boston to Yarmouth, N.S., where an elder brother, Moses, had settled in the previous year. This first visit to Yarmouth was disappointing for Scott, since most of his time and hard-earned savings were spent looking after the affairs of his sick brother. Returning to Roxbury in the autumn of the same year, he went to work in the shoemaking business of his old master, Goddard. Because of personal differences, however, he soon left Goddard's employ and tried to establish his own trade. Unsuccessful in this venture, he returned to Yarmouth in April 1765. There he was able to earn a small amount of money as a fisherman, and with his savings he began putting down roots in the community. He built a log house in December 1765, and on 14 March 1768 he married Lucy Ring, the daughter of a local trader and fisherman, in a ceremony conducted by the Reverend Ebenezer Moulton*, an itinerant Baptist preacher. Later in the year the couple moved into a frame-house which Scott had built.

The year 1768 was significant in other ways for Scott. Since his childhood days he had retained a deep interest in religious matters, and in the autumn of 1768 he "began to lead in Public Worship at the desire of the people." When in 1770 he was invited to become minister he refused because of divisions within the church based on pro- and anti- evangelical positions. But after a visit by two Congregational ministers from Massachusetts, Solomon Reed and Sylvanus Conant of Middleboro, enough unity was established to encourage Scott to accept the call when it was renewed in January 1772. In March, Scott and a committee from the church traveled to Middleboro, where a council of Congregational ministers organized by Reed and Conant was to examine Scott's qualifications and suitability for the ministry. After a rigorous examination stretching over a two-week period, during which he had to preach and answer doctrinal questions put to him by the other minister, Scott was formally ordained on 28 April 1772. This was a dramatic moment in Scott's life, for here was he, a struggling farmer from a remote settlement, being approved for the ministry by a committee of well-known New England pastors, all holding degrees from Harvard or Yale. Scott was proud of this distinction and from this time on he took seriously the duty of defending the Congregational establishment against evangelical attacks. He returned to Yarmouth in May as the community's first regularly ordained Congregational minister and remained at that post until 1795, when he left to become the minister at Bakerstown (Minot, Maine).

The most interesting aspect of Scott's life during the period from 1772 to 1795 was his role in the great religious revival which swept through Nova Scotia in the 1770s, 1780s, and 1790s but which was particularly intense during the last years of the American Revolutionary War. At the height of the revival in the early 1780s Scott became the leading spokesman for those opposed to the work of Henry Alline*, the itinerant evangelical preacher. Besides visiting and corresponding with other communities throughout the colony in an effort to stem the tide of revivalism, Scott found time to write lengthy and cogent theological tracts designed to refute Alline's often peculiar religious ideas. His major work, A brief view of the religious tenets and sentiments, lately published and spread in the province of Nova Scotia, was a careful and detailed critique of Alline based on the writings of Jonathan Edwards, the famous Massachusetts minister and theologian, whose "new diversity" reconciled the evangelical position with a respect for the existing Congregational establishment. Yet in spite of such efforts, impressive for a man with no formal theological training, Scott was not successful in solidifying the anti-revivalist cause. His weighty theological critiques made scant impression on the farmers and fisherman who responded more easily to the simplistic and emotional preaching of Alline. Even in Yarmouth itself Scott lost most of his people to the revival and became in the early 1780s an embittered and isolated figure. Although he remained as the Congregational minister, his sense of failure in these years contributed to his decision to leave Yarmouth for Bakerstown in 1794.

Jonathan Scott did have his share of human frailties: he had a tendency to be short-tempered in a crisis, and the forthright manner in which he demanded increases in his salary did little to enhance his popularity during the years of the revival. On the whole, however, his failure to obtain support had less to do with his own shortcomings than with the conditions in the colony and the effectiveness of Alline's preaching. Scott was much better informed theologically than Alline, particularly in his knowledge of Jonathan Edwards's writings. He was more temperate than Alline, more reasonable, more tolerant, and more cautious in making pronouncements on complicated moral and doctrinal issues. He was also more humane in the sense that he accepted man's limitations when it came to comprehending the mysteries of God's universe. Unsure at times of his own religious condition, he was modest enough to believe that he had not found final solutions to contemporary problems. For this reason, he became somewhat out of place in the 1770s and 1780s, when simplistic preaching, emotional uplift, and a sense of certainty were the order of the day.

Gordon Stewart.

Family Members

-

![]()

Deacon John Scott

1768–1855

-

![]()

Lydia Scott Verrill

1770–1816

-

![]()

Samuel Scott

1772–1854

-

![]()

Jonathan Edwards Scott

1773–1822

-

Lucretia Scott Redding

1774–1822

-

![]()

Olive Scott Tedford

1775–1860

-

![]()

Joseph Scott

1785–1800

-

![]()

Elizabeth Scott

1786–1869

-

![]()

Lucy Scott

1788–1793

-

Benjamin Scott

1789–1870

-

Capt George Scott

1791–1825

-

![]()

Mary Scott Scales

1793–1827

-

![]()

Sylvanus Scott

1795–1807

Advertisement

Explore more

Sponsored by Ancestry

Advertisement