E.E. and his wife, plus two of his sisters, are instead with his wife's sisters at Elmwood, placed across the street from Barre's First Congregational Church. Mourners could walk with the coffin, from the church service, to the burial at Elmwood.

Of the two cemeteries, Elmwood's entries seem less completely listed. it's as if more survivors had moved away, so lost track of family graves left behind.

THEIR GIFT TO US.

E.E. and his Angelia were pro-education. "Academies" were a newish invention, their success allowing the introduction of public high schools and "normal schools" for training teachers, ideas carried outside Vermont into the states stretched westward along the Great Lakes. Even though he and wife Angelia were without children of their own, he became a strong supporter of the Barre Academy. His wife did the same for the Montpelier Academy in her will, letting far more attend the academies than if their large financial contributions had not been made.

OCCUPATIONS. Forced to give up farming due to illness, he learned the law and became a business lawyer. (That was easily done then, in less time than true now.)

He was good at both law and business, sometimes working with his brothers-in-law in their merchandizing chain, with one, for example, long-established in Evanston, Ill. E.E.'s other activities included promoting a local bank for Barre and in raising bond monies to attract a railroad branch and depot station, with similar monies raised for surrounding towns, not just for Barre.

FAMILY. His parents were Samuel French and Lydia Sampson, Methodists who believed in pursuing the social good. They were said to have moved to Barre, Vermont, around 1842, where he would meet, love, and marry a woman named Angelia French, their ceremony in 1845. Two of his siblings' markers at Wilson give earlier death dates than 1842, with his sister Lydia having died in Jan. of 1841, her Vermont death record giving Barre as the location. Samuel French the younger died two decades earlier, his marker dates set to 1817-1822. Is his marker a "cenotaph", a bodiless memorial to a child who died elsewhere? Or, had the family been sufficiently near Barre to use its cemetery in 1822, but did not move inside Barre boundaries until later? A record for his parents' marriage says they married in next-door Orange County in 1807, in Corinth, their vows in front of a JP.

RELATED? PROVEN NOT, IN 2014.

The two sets of Frenches who parented E.E. and wife Angelia were not related to each other. This was proven recently, circa 2014, by modern DNA tests on males from their two different family hearthplaces in the Mass. Bay Colony. These were Salisbury for him, Braintree for her, at opposite ends of old Boston. As of 2020, these were put into DNA sets labelled Group 3 and Group 25, inside a study of surname French at the FamilyTreeDNA website.

(ORIGIN COMMENTS. Male DNA studies for surname French are supervised by volunteers with the FFA, FrenchFamilyAssoc.com, with E.E.s tree plotted as Chart 4, Edward French of Salisbury, and wife Angelia's as John French of Quincy, Braintree, and Dorchester, the different places related to boundary changes, causing church re-assignments, not moves.

The first immigrants of both places came from Great Britain in Puritan days. His father's birthplace of Salisbury was up by future Maine. His immigrant ancestor, Edward, who d.1674, settled in Salisbury, after entering the colonies at Ipswich, both places today in Essex County. The early economy depended on lumber sent down the Merrimac River to build ships for use at the coast.

Most Methodists there did not arrive as Methodist, but would have attended the subsidized "King's chapels", not turning Methodist until the Revolution cut ties to the King and thus the King's Church. Overall, the Salisbury area was sparsely settled compared to areas farther south. Out-migration to Vermont in his father's day typically followed the Merrimac upstream into what became New Hampshire, before crossing over the Green Mountains into Vermont, with a mountain pass making that easier.

In contrast, Angelia's first immigrants came into old Braintree, Mass, with shipbuilding next door in old Weymouth. Their general area's early economy had more than shipbuilding to attract a population. Some of her Frenches were connected to the old mills. Some had harvestable salt marches. More unusual, "bog iron" apparently was available, until it was used up, accounting for talk of the old forge at Braintree. Modern Braintree's Elm Street was put alongside an "old forge road" seen on some old maps. John Winthrop governed the associated haymaking and milling and forging in Boston's southern outskirts as corporate businesses. He did so from a very tiny old Boston. Still a peninsula, the corporate and government officials were housed in the peninsula's interior, deemed easier to defend against attack due to being surrounded by water on three sides.

The so-called Dorchester neck gave the main access to Boston by land, to what was otherwise still surrounded by water. Carts could travel into the southside of old Boston on the neck. Other sides of Boston, north and west, were to be approached by boats and ferries.

Old Braintree was southeasterly and just outside the neck. It went from one to three churches, not just with population growth, but also with the unhappiness of Angelia's ancestor Frenches and others, in having to cross swamps and then go uphill, to get to the first church built, with some deaths in bad weather and reduced attendance then.

The first church of old Braintree was not located centrally for the convenience of the average church member, but off-center, a commercial advantage to businesses wanting to locate near the church. All were on a high point visible to incomers from the sea, sharing the location advantage of the old Merry Mount trading post, earlier destroyed by religiously more extreme "separatists" coming north to do business, from the old Plymouth colony south of Weymouth. The main business route north out of old Plymouth, though Braintree, became Commercial Street, which ran close to the old immigrants' homestead. Her immigrant ancestors, John and Grace French, receiving their "starter land" in 1640 as a "freedman"grant, had their farmstead just northeast of the intersection of modern Elm and modern Commercial street, "on the way" from the Plymouth colony to the neck. Braintree's second church was located on what became Elm Street, which like the old forge road, whose path followed the Monatiquot River on the river's north side. Their son Dependence would assume their homestead, according to materials kept by the FFA. His branch would be long in old Braintree, his son John said to be early to mill on the Cochato, a north-south tributary to, so upstream of the east-west Monatiquot. That John's family was active in beginning the third church, that church's third precinct now more or less modern Randolph.

In contrast, Angelia's two families, not descended of Dependence, left Braintree before the third church formed. For over a century, the church to attend was assigned by location of land owned. Thus, no denomination was declared, until the precinct with the oldest church building, distant from the Frenches' homestead separated, pre-Revolution, by declaring themselves the town of Quincy and their previously subsidized church Unitarian. The other two churches, closer to the Frenches, supported "by subscription", rather than subsidized by the larger town, waited until post-Revolution to declare themselves First Congregational of two newly formed Boston suburbs, Braintree and Randolph, respectively.

Out-migrations from a mother church at old Dorchester were occurring before the 1640 declaration of "free men" created the first church of old Braintree. One set, excluding Angelia's Frenches, found better farmland at what became the Windsor colony in Connecticut. By going up the Connecticut River from Windsor, they found themselves back in Massachusetts, but at its western end, key places being Springfield and Northampton. Travel further up the Conn. River took migrants into future Vermont, which did not declare as a state until 1790.

The other pathways to Vermont were inland, used by Angelia's Frenches, who descended of younger sons of John and Grace, the younger brothers to Dependence and younger cousins to John of Cochato. Angelia's parents were distant cousins from two sets who left Braintree early, after the second church had its first burials at its Elm Street cemetery.

The easier-to-track set went up to frontier towns that were essentially military posts at the north edge of the colony, especially Athol, in what became Worcester County. Adult children who married at Athol then moved northward with Dodge in-laws to find better land, later, in Vermont.

The harder-to-track set left old Braintree not by choice, but as the parents died a year apart, becoming some of the first burials at Elm Street. The dying mother arranged things in a way that left her eldest children well-established in Braintree, but some young children were "farmed out", with one or two "sent somehow" to and through NH. Mendon and Milton in Worcester County and North Bridgewater in Plymouth County were in-between places for parents before those out-migrations to Vermont and/or New Hampshire completed.

NOT BLOOD-RELATIVES, BUT TOLD THEY WERE.

Pre-DNA, with Angela's Frenches not on one clear migration path and knowing her parents were distant cousins, Ephraim and Angelia apparently found two things believable:

(1) Not only were they related, but also

(2) All people surnamed French descended from one family back in Scotland.

How did that mis-information about themselves change their lives? They had no children of their own, with nothing further said as to how and why. Without their own, they doted on some nieces and nephews.

SHARED INTERESTS. His own relatives favored the Methodists and their charitable doings, while his in-laws tended to be Congregationalists, who believed in public discussions before making key decisions. Their differences were not great, however, as he and his wife Angelia showed similar values, his interest in the Barre Academy matched by her supporting the Montpelier Academy, and then a hospital for Barre.

His place of death could be left blank to avoid confusion for people relying on different written records while trying to find his grave. The grave is in Vermont, the death place was in Illinois, near Chicago.

Yet, the death record is found in Vermont. Handwritten, citing pneumonia, it was signed by a clerk located in Barre, in Washington County, and does not mention Illinois.

His death place was in a biography written for him in a local Vermont book called a "gazetteer", apparently in the year after his death. The date makes it likely to be highly accurate, given the widow would have been asked to submit the material when all was fresh in her mind.

The gazetteer story said he had been on his way home from California. (Angelia's relatives there had included descendants of Dependence, a Mary Eliza French, widowed while young by a first husband who had started a weekly paper in Salinas before his death, and her sister, the Climena French who had married fellow teacher Samuel Shearer. Samuel was also widowed by his first wife. Samuel still lived south of the San Fran Bay, after becoming a Supt. of Schools and taking over the Salinas weekly paper.)

E. E. sickened by the time they had reached Denver, Colorado, then was taken to "his brother's house in Evanston, Illinois". There, he died.

Evanston points to the house of his wife Angelia's brother, Orvis, with Evanston, at Chicago's north edge. The location of Orvis was well-documented, as his large brick mansion was able to take in many refugees of Chicago's infamous Great Fire, as brick did not burn. Orvis' thriving merchant location, however, was destroyed. He "went with the flow", changing his business to hotel keeper, adapting his mansion longer-term to hotel use.

Stopping at Evanston would have been in Cook County, Illinois. No obvious records have been found there. His record in Vermont was may be done for shipping purposes. (His body being shippable back to Vermont was made possible by family business knowledge of rail connections and maybe a new type of coffin and early rail refrigeration?)

Both old sources agreed as to his death date and his parents' names.

VERMONT DEATH RECORD:

FamilySearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:S3HY-DTSS-S3X

HIS BIOGRAPHY, pages 92-96:

"Gazetteer of Washington County, Vt., 1783-1889", edited by William Adams

(WARNING: The biography's leading line about a distant genealogy involving a place called Thorndic in Scotland is in error. There was such a place, though spelled differently. Photos of the Scottish settlement on the web show a ranch-like set-up with pastures and barns, both sheep and cattle in the area, its "castle" more like a small and short garrison, than a large and tall fairy-tale structure.

The area was indeed run by a family surnamed French, one with a long, well-documented lineage. That was before its young heir died long ago and inheritance apparently skipped to cousins who could not afford the place, so sold it. The selling cousins who stayed local would need descendants to submit male DNA tests to the FFA to test their connections to any others named French, as the paper trail apparently stopped back there, none of the sellers was here in the States.

Those truths are about ONE line of Frenches. Bigger parts claim, wrongly, subtly, that all people surnamed French descended from that very small set in Scotland, that, in particular, the Thorndic descendant coming to America and father to all Frenches here was John French of Braintree. Again, (1) no man named French and recently of Thondic has taken a DNA test and found it to match those taken by descendants of the Braintree John French and (2) the FFA DNA study had detected at least 12 different make DNA lines by 2014 or so, clealry without the same ancestor.

SIDE NOTES. The name Ephraim is Old Testament. Ephraim French was a surprisingly common name in his own era. Many in certain parts of New England sharing both his first and last names. Many of those were from families that, like his and also Angelia's, arrived in old Massachusetts in the early Puritan era.

Most Ephraim Frenches, however, were unrelated to him. More were instead of still another DNA, a third male DNA. These were the Puritan Frenches that went to Ipswich, which is nearish Salisbury, but not the same as Salisbury, confusing some. A subset went later to Rehoboth, down near Rhode Island, with some of their territory re-assigned in the 1800s to East Providence, RI. The re-assignment affected the grave of husbandsman John Kingsley, whose will chastised "taylor John French" for taking Kingsley's daughter where she could not wait on Kingsley in his dotage.

The John French of Braintree, in contrast, with his sons and grandsons, had zero tailors in their mix. There were tanners, yes, millers, yes, blacksmiths, yes, bricklayers, yes, farmers and orchardists and pasture keepers in droves. They were not in tailoring with its very different set of skills, taught parents- to-sons in the Frenches first to Ipswich. Two of the Ipswich John French's sons, his eldest son John and a younger son Thomas, names too common to track well, ultimately went to Rehoboth to be near their Kingsley grandfather and uncles, one early, the other later, his family largely destroyed after trying to settle in the infamous Deerfield further north too early, before its native occupants, supported by the French military, were ready to give up their seasonal use of the area for summertime gardens and annual corn crops.

MORE ON ANGELIA'S BRAINTREE SIDE. Even without DNA, it should have been clearfrom many other differences that the multiple John Frenches immigrating were not the same man.

, with John's two eldest sons, the "Christmas day twins", to take the last sliver of land just outside Randolph, once called Stoughton Corner and largely matching modern Avon. Their next younger brother Abiathar/Abiather could stay if he had no ambitions past bricklayer. Wanting to farm, however, he and his teen son and some in-laws went together to the west end of the Bay Colony. They would be part of a new church formed at Westhampton as the Revolution began, with Angelia's most easily tracked relatives instead to their northeast, at the north-central end of the colony, at Athol. Later, a serious religious division of some sort arose at Athol. Her more trackable end of the family split apart in reaction, her end's majority to go with Dodge in-laws to Vermont, with more success, as Dodges and Frenches acted as a support system for each other, the religious minority to try war-destroyed NY instead, with less success, hurt by bringing too few relatives as a support system. This writer's spouse seems to have descended of the Abiathers, who with certain in-laws, left a trail of women named Climena, as they moved from Westhampton to northeastern Ohio, preWar of 1812, a handy thing as good birth records disappeared once churches split apart into too many denominations. Governments could have made-up for this with public records. Outside Vermont and eastern Mass., counties and states and territories were too slow in starting public birth records, causing multiple "silent decades" where connections of parents to children have neither birth nor baptismal records as back up, but must rely on extreme proximity, moving to new places together, exchanging land in deeds and wills that give maiden names, sharing in-laws as two sisters married two brothers, and naming children oddly. (in those connected to the Abiathers, Climena became popular among teacher-types but for only a generation or two, did so around the time of the Greek Revival in fancier architecture. Using Alvord instead of Alfred as a boy's name began when Alvords were picked-up as in-laws in the Westhampton area, with Abiathar the junior marrying Beriah Alvord before multiple sons went into northeast Ohio, with a grandson called Alvord French hiding that oddity , calling himself A. French once in California, a great-grandson in Michigan revealed on a Census as Alvord French by his mother, then hiding that oddity by going by A.O. French as an adult.) If there is only one such things, there's easily no connection. If there are ten such things, a connection turns very likely ("convergent validity") Having two John French with two sons John and Thomas in different places means nothing by itself, as the combination was too common. Having the two Johns instead in the same place with a sharing of odd names including in-laws may make a DNA check worthwhile

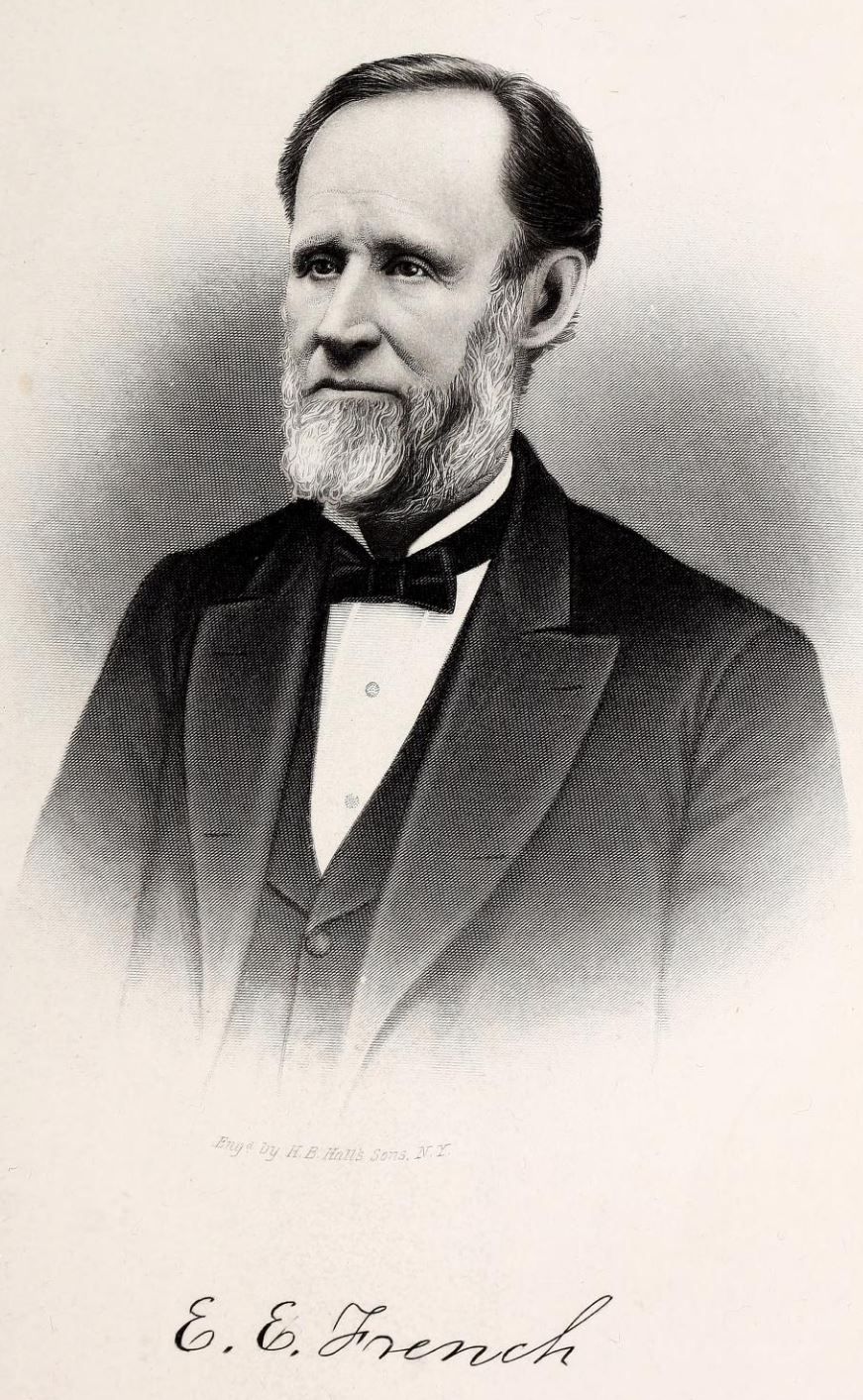

HIS UNIQUENESS. He was the only Ephraim with the surname Eddy as his middle name, the only one born in Washington Twp. in what had become Orange County, Vermont. He was the only Ephraim in Barre, Vermont, whose parent Frenches originated from Salisbury, Mass. He was the only one married to a woman whose name reminds one of angel's wings.

His siblings are listed in the gazzeteer source.

E.E. and his wife, plus two of his sisters, are instead with his wife's sisters at Elmwood, placed across the street from Barre's First Congregational Church. Mourners could walk with the coffin, from the church service, to the burial at Elmwood.

Of the two cemeteries, Elmwood's entries seem less completely listed. it's as if more survivors had moved away, so lost track of family graves left behind.

THEIR GIFT TO US.

E.E. and his Angelia were pro-education. "Academies" were a newish invention, their success allowing the introduction of public high schools and "normal schools" for training teachers, ideas carried outside Vermont into the states stretched westward along the Great Lakes. Even though he and wife Angelia were without children of their own, he became a strong supporter of the Barre Academy. His wife did the same for the Montpelier Academy in her will, letting far more attend the academies than if their large financial contributions had not been made.

OCCUPATIONS. Forced to give up farming due to illness, he learned the law and became a business lawyer. (That was easily done then, in less time than true now.)

He was good at both law and business, sometimes working with his brothers-in-law in their merchandizing chain, with one, for example, long-established in Evanston, Ill. E.E.'s other activities included promoting a local bank for Barre and in raising bond monies to attract a railroad branch and depot station, with similar monies raised for surrounding towns, not just for Barre.

FAMILY. His parents were Samuel French and Lydia Sampson, Methodists who believed in pursuing the social good. They were said to have moved to Barre, Vermont, around 1842, where he would meet, love, and marry a woman named Angelia French, their ceremony in 1845. Two of his siblings' markers at Wilson give earlier death dates than 1842, with his sister Lydia having died in Jan. of 1841, her Vermont death record giving Barre as the location. Samuel French the younger died two decades earlier, his marker dates set to 1817-1822. Is his marker a "cenotaph", a bodiless memorial to a child who died elsewhere? Or, had the family been sufficiently near Barre to use its cemetery in 1822, but did not move inside Barre boundaries until later? A record for his parents' marriage says they married in next-door Orange County in 1807, in Corinth, their vows in front of a JP.

RELATED? PROVEN NOT, IN 2014.

The two sets of Frenches who parented E.E. and wife Angelia were not related to each other. This was proven recently, circa 2014, by modern DNA tests on males from their two different family hearthplaces in the Mass. Bay Colony. These were Salisbury for him, Braintree for her, at opposite ends of old Boston. As of 2020, these were put into DNA sets labelled Group 3 and Group 25, inside a study of surname French at the FamilyTreeDNA website.

(ORIGIN COMMENTS. Male DNA studies for surname French are supervised by volunteers with the FFA, FrenchFamilyAssoc.com, with E.E.s tree plotted as Chart 4, Edward French of Salisbury, and wife Angelia's as John French of Quincy, Braintree, and Dorchester, the different places related to boundary changes, causing church re-assignments, not moves.

The first immigrants of both places came from Great Britain in Puritan days. His father's birthplace of Salisbury was up by future Maine. His immigrant ancestor, Edward, who d.1674, settled in Salisbury, after entering the colonies at Ipswich, both places today in Essex County. The early economy depended on lumber sent down the Merrimac River to build ships for use at the coast.

Most Methodists there did not arrive as Methodist, but would have attended the subsidized "King's chapels", not turning Methodist until the Revolution cut ties to the King and thus the King's Church. Overall, the Salisbury area was sparsely settled compared to areas farther south. Out-migration to Vermont in his father's day typically followed the Merrimac upstream into what became New Hampshire, before crossing over the Green Mountains into Vermont, with a mountain pass making that easier.

In contrast, Angelia's first immigrants came into old Braintree, Mass, with shipbuilding next door in old Weymouth. Their general area's early economy had more than shipbuilding to attract a population. Some of her Frenches were connected to the old mills. Some had harvestable salt marches. More unusual, "bog iron" apparently was available, until it was used up, accounting for talk of the old forge at Braintree. Modern Braintree's Elm Street was put alongside an "old forge road" seen on some old maps. John Winthrop governed the associated haymaking and milling and forging in Boston's southern outskirts as corporate businesses. He did so from a very tiny old Boston. Still a peninsula, the corporate and government officials were housed in the peninsula's interior, deemed easier to defend against attack due to being surrounded by water on three sides.

The so-called Dorchester neck gave the main access to Boston by land, to what was otherwise still surrounded by water. Carts could travel into the southside of old Boston on the neck. Other sides of Boston, north and west, were to be approached by boats and ferries.

Old Braintree was southeasterly and just outside the neck. It went from one to three churches, not just with population growth, but also with the unhappiness of Angelia's ancestor Frenches and others, in having to cross swamps and then go uphill, to get to the first church built, with some deaths in bad weather and reduced attendance then.

The first church of old Braintree was not located centrally for the convenience of the average church member, but off-center, a commercial advantage to businesses wanting to locate near the church. All were on a high point visible to incomers from the sea, sharing the location advantage of the old Merry Mount trading post, earlier destroyed by religiously more extreme "separatists" coming north to do business, from the old Plymouth colony south of Weymouth. The main business route north out of old Plymouth, though Braintree, became Commercial Street, which ran close to the old immigrants' homestead. Her immigrant ancestors, John and Grace French, receiving their "starter land" in 1640 as a "freedman"grant, had their farmstead just northeast of the intersection of modern Elm and modern Commercial street, "on the way" from the Plymouth colony to the neck. Braintree's second church was located on what became Elm Street, which like the old forge road, whose path followed the Monatiquot River on the river's north side. Their son Dependence would assume their homestead, according to materials kept by the FFA. His branch would be long in old Braintree, his son John said to be early to mill on the Cochato, a north-south tributary to, so upstream of the east-west Monatiquot. That John's family was active in beginning the third church, that church's third precinct now more or less modern Randolph.

In contrast, Angelia's two families, not descended of Dependence, left Braintree before the third church formed. For over a century, the church to attend was assigned by location of land owned. Thus, no denomination was declared, until the precinct with the oldest church building, distant from the Frenches' homestead separated, pre-Revolution, by declaring themselves the town of Quincy and their previously subsidized church Unitarian. The other two churches, closer to the Frenches, supported "by subscription", rather than subsidized by the larger town, waited until post-Revolution to declare themselves First Congregational of two newly formed Boston suburbs, Braintree and Randolph, respectively.

Out-migrations from a mother church at old Dorchester were occurring before the 1640 declaration of "free men" created the first church of old Braintree. One set, excluding Angelia's Frenches, found better farmland at what became the Windsor colony in Connecticut. By going up the Connecticut River from Windsor, they found themselves back in Massachusetts, but at its western end, key places being Springfield and Northampton. Travel further up the Conn. River took migrants into future Vermont, which did not declare as a state until 1790.

The other pathways to Vermont were inland, used by Angelia's Frenches, who descended of younger sons of John and Grace, the younger brothers to Dependence and younger cousins to John of Cochato. Angelia's parents were distant cousins from two sets who left Braintree early, after the second church had its first burials at its Elm Street cemetery.

The easier-to-track set went up to frontier towns that were essentially military posts at the north edge of the colony, especially Athol, in what became Worcester County. Adult children who married at Athol then moved northward with Dodge in-laws to find better land, later, in Vermont.

The harder-to-track set left old Braintree not by choice, but as the parents died a year apart, becoming some of the first burials at Elm Street. The dying mother arranged things in a way that left her eldest children well-established in Braintree, but some young children were "farmed out", with one or two "sent somehow" to and through NH. Mendon and Milton in Worcester County and North Bridgewater in Plymouth County were in-between places for parents before those out-migrations to Vermont and/or New Hampshire completed.

NOT BLOOD-RELATIVES, BUT TOLD THEY WERE.

Pre-DNA, with Angela's Frenches not on one clear migration path and knowing her parents were distant cousins, Ephraim and Angelia apparently found two things believable:

(1) Not only were they related, but also

(2) All people surnamed French descended from one family back in Scotland.

How did that mis-information about themselves change their lives? They had no children of their own, with nothing further said as to how and why. Without their own, they doted on some nieces and nephews.

SHARED INTERESTS. His own relatives favored the Methodists and their charitable doings, while his in-laws tended to be Congregationalists, who believed in public discussions before making key decisions. Their differences were not great, however, as he and his wife Angelia showed similar values, his interest in the Barre Academy matched by her supporting the Montpelier Academy, and then a hospital for Barre.

His place of death could be left blank to avoid confusion for people relying on different written records while trying to find his grave. The grave is in Vermont, the death place was in Illinois, near Chicago.

Yet, the death record is found in Vermont. Handwritten, citing pneumonia, it was signed by a clerk located in Barre, in Washington County, and does not mention Illinois.

His death place was in a biography written for him in a local Vermont book called a "gazetteer", apparently in the year after his death. The date makes it likely to be highly accurate, given the widow would have been asked to submit the material when all was fresh in her mind.

The gazetteer story said he had been on his way home from California. (Angelia's relatives there had included descendants of Dependence, a Mary Eliza French, widowed while young by a first husband who had started a weekly paper in Salinas before his death, and her sister, the Climena French who had married fellow teacher Samuel Shearer. Samuel was also widowed by his first wife. Samuel still lived south of the San Fran Bay, after becoming a Supt. of Schools and taking over the Salinas weekly paper.)

E. E. sickened by the time they had reached Denver, Colorado, then was taken to "his brother's house in Evanston, Illinois". There, he died.

Evanston points to the house of his wife Angelia's brother, Orvis, with Evanston, at Chicago's north edge. The location of Orvis was well-documented, as his large brick mansion was able to take in many refugees of Chicago's infamous Great Fire, as brick did not burn. Orvis' thriving merchant location, however, was destroyed. He "went with the flow", changing his business to hotel keeper, adapting his mansion longer-term to hotel use.

Stopping at Evanston would have been in Cook County, Illinois. No obvious records have been found there. His record in Vermont was may be done for shipping purposes. (His body being shippable back to Vermont was made possible by family business knowledge of rail connections and maybe a new type of coffin and early rail refrigeration?)

Both old sources agreed as to his death date and his parents' names.

VERMONT DEATH RECORD:

FamilySearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:S3HY-DTSS-S3X

HIS BIOGRAPHY, pages 92-96:

"Gazetteer of Washington County, Vt., 1783-1889", edited by William Adams

(WARNING: The biography's leading line about a distant genealogy involving a place called Thorndic in Scotland is in error. There was such a place, though spelled differently. Photos of the Scottish settlement on the web show a ranch-like set-up with pastures and barns, both sheep and cattle in the area, its "castle" more like a small and short garrison, than a large and tall fairy-tale structure.

The area was indeed run by a family surnamed French, one with a long, well-documented lineage. That was before its young heir died long ago and inheritance apparently skipped to cousins who could not afford the place, so sold it. The selling cousins who stayed local would need descendants to submit male DNA tests to the FFA to test their connections to any others named French, as the paper trail apparently stopped back there, none of the sellers was here in the States.

Those truths are about ONE line of Frenches. Bigger parts claim, wrongly, subtly, that all people surnamed French descended from that very small set in Scotland, that, in particular, the Thorndic descendant coming to America and father to all Frenches here was John French of Braintree. Again, (1) no man named French and recently of Thondic has taken a DNA test and found it to match those taken by descendants of the Braintree John French and (2) the FFA DNA study had detected at least 12 different make DNA lines by 2014 or so, clealry without the same ancestor.

SIDE NOTES. The name Ephraim is Old Testament. Ephraim French was a surprisingly common name in his own era. Many in certain parts of New England sharing both his first and last names. Many of those were from families that, like his and also Angelia's, arrived in old Massachusetts in the early Puritan era.

Most Ephraim Frenches, however, were unrelated to him. More were instead of still another DNA, a third male DNA. These were the Puritan Frenches that went to Ipswich, which is nearish Salisbury, but not the same as Salisbury, confusing some. A subset went later to Rehoboth, down near Rhode Island, with some of their territory re-assigned in the 1800s to East Providence, RI. The re-assignment affected the grave of husbandsman John Kingsley, whose will chastised "taylor John French" for taking Kingsley's daughter where she could not wait on Kingsley in his dotage.

The John French of Braintree, in contrast, with his sons and grandsons, had zero tailors in their mix. There were tanners, yes, millers, yes, blacksmiths, yes, bricklayers, yes, farmers and orchardists and pasture keepers in droves. They were not in tailoring with its very different set of skills, taught parents- to-sons in the Frenches first to Ipswich. Two of the Ipswich John French's sons, his eldest son John and a younger son Thomas, names too common to track well, ultimately went to Rehoboth to be near their Kingsley grandfather and uncles, one early, the other later, his family largely destroyed after trying to settle in the infamous Deerfield further north too early, before its native occupants, supported by the French military, were ready to give up their seasonal use of the area for summertime gardens and annual corn crops.

MORE ON ANGELIA'S BRAINTREE SIDE. Even without DNA, it should have been clearfrom many other differences that the multiple John Frenches immigrating were not the same man.

, with John's two eldest sons, the "Christmas day twins", to take the last sliver of land just outside Randolph, once called Stoughton Corner and largely matching modern Avon. Their next younger brother Abiathar/Abiather could stay if he had no ambitions past bricklayer. Wanting to farm, however, he and his teen son and some in-laws went together to the west end of the Bay Colony. They would be part of a new church formed at Westhampton as the Revolution began, with Angelia's most easily tracked relatives instead to their northeast, at the north-central end of the colony, at Athol. Later, a serious religious division of some sort arose at Athol. Her more trackable end of the family split apart in reaction, her end's majority to go with Dodge in-laws to Vermont, with more success, as Dodges and Frenches acted as a support system for each other, the religious minority to try war-destroyed NY instead, with less success, hurt by bringing too few relatives as a support system. This writer's spouse seems to have descended of the Abiathers, who with certain in-laws, left a trail of women named Climena, as they moved from Westhampton to northeastern Ohio, preWar of 1812, a handy thing as good birth records disappeared once churches split apart into too many denominations. Governments could have made-up for this with public records. Outside Vermont and eastern Mass., counties and states and territories were too slow in starting public birth records, causing multiple "silent decades" where connections of parents to children have neither birth nor baptismal records as back up, but must rely on extreme proximity, moving to new places together, exchanging land in deeds and wills that give maiden names, sharing in-laws as two sisters married two brothers, and naming children oddly. (in those connected to the Abiathers, Climena became popular among teacher-types but for only a generation or two, did so around the time of the Greek Revival in fancier architecture. Using Alvord instead of Alfred as a boy's name began when Alvords were picked-up as in-laws in the Westhampton area, with Abiathar the junior marrying Beriah Alvord before multiple sons went into northeast Ohio, with a grandson called Alvord French hiding that oddity , calling himself A. French once in California, a great-grandson in Michigan revealed on a Census as Alvord French by his mother, then hiding that oddity by going by A.O. French as an adult.) If there is only one such things, there's easily no connection. If there are ten such things, a connection turns very likely ("convergent validity") Having two John French with two sons John and Thomas in different places means nothing by itself, as the combination was too common. Having the two Johns instead in the same place with a sharing of odd names including in-laws may make a DNA check worthwhile

HIS UNIQUENESS. He was the only Ephraim with the surname Eddy as his middle name, the only one born in Washington Twp. in what had become Orange County, Vermont. He was the only Ephraim in Barre, Vermont, whose parent Frenches originated from Salisbury, Mass. He was the only one married to a woman whose name reminds one of angel's wings.

His siblings are listed in the gazzeteer source.

Gravesite Details

EPHRAIM E. FRENCH// ANGELIA FRENCH, HIS WIFE

Family Members

Advertisement

Advertisement