Wheeler, who joined the Army in 1995, was assigned to Headquarters, U.S. Army Special Operations Command at Fort Bragg, North Carolina.

====

ARMY TIMES

U.S. reports first death in combat with Islamic State

He is the first American service member killed in action by enemy fire while fighting Islamic State militants.

Wheeler, who was from Roland, Oklahoma, joined the Army as an infantryman. He served in the 75th Ranger Regiment, deploying three times to support combat operations in Iraq and Afghanistan, before being assigned to USASOC headquarters. He deployed 11 times after that to Iraq and Afghanistan, according to information released by USASOC.

Wheeler died from enemy gunfire near Hawijah, Iraq.

He was part of a team of dozens of U.S. special operations troops who joined Kurdish peshmerga fighters in a predawn raid of a detention facility run by the Islamic State group.

The U.S. and Kurdish forces killed several Islamic State militants and detained five others, defense officials have said.

In addition to Wheeler, four peshmerga soldiers were wounded.

The raid freed about 70 hostages whose lives officials said were in imminent danger.

=======

Joshua Wheeler: Cherokee Warrior, First US Casualty Fighting ISIS

Joshua L. Wheeler, 39-year-old Cherokee warrior, is the latest American lost in the fog of the second Iraq war, which is supposed to have ended. President George W. Bush announced the end of "major combat operations" in Iraq on May 1, 2003. President Barack Obama announced the end of "combat operations" in Iraq on August 31, 2010. President Bush, in the parlance of our times, "walked back" his claim later, and the video of President Obama's claim has been discreetly cleansed from the Whitehouse.gov website.

Master Sergeant Wheeler holds the distinction of being the first known U.S. casualty in the fight against ISIS. Since U.S. special operators are on the ground in several nations with which the U.S. is not at war working against ISIS, it is not clear that we the public would be told if one were killed in action. Because of the many people his life touched, Joshua Wheeler's loss is not one that could go unnoticed.

Sergeant Wheeler was career Army, assigned to the elite and secretive Delta Force. He joined the Army in 1995, the Rangers in 1997, and special ops in 2004. Because of the nature of his work, his family knew little, and we don't know as much as we otherwise might about his death. He was deployed 14 times that we know of and he received 11 Bronze Stars that we know of. In the special ops business, sometimes even honors are secret.

The details of the fight that took Sgt. Wheeler's life are not knowable with certainty through the fog, but the morality of the particular battle is.

Wheeler died fighting ISIS, the radical Islamist lunatics known for all the creative ways they kill hostages on video. Helpless prisoners who cannot resist have been beheaded, thrown off tall buildings, burned alive, drowned, and blown up by explosives. Video of these crimes comes from ISIS propaganda, not U.S. propaganda. Several battles have ended with videos of POWs being marched into waiting mass graves and executed by gunfire.

Yes, these are war crimes. This would be why they hide their faces more often than not. That's the morality of it. War crimes stand above any particular nation's interest and the duty to prevent them is clear in international law.

Wheeler died in a Delta Force raid on a facility holding ISIS prisoners near Hawijah in Northern Iraq. Human intelligence had predicted the prisoners were to be executed the next day and aerial reconnaissance showed a mass grave already dug.

The facility was thought to hold prisoners from the Kurdish peshmerga militia and we are told that the peshmerga had the lead in the operation. The Army's elite 160th Special Operations Aviation Regiment, known in the military as "Night Stalkers," airlifted Kurdish and U.S. soldiers to the ISIS prison near the witching hour. Special Forces say they "own the night."

One version of the encounter said the peshmerga were unable to breach the wall protecting the ISIS prison. Another version said the peshmerga came under fire that stalled their advance. Both could be true.

A U.S. military official gave Foreign Policy—which has in the past had very good sources—a simple explanation how the 30 or so special operators on the scene of a mission where their only role was "advise and support" got in a firefight.

"Support" was supposed to mean to protect the Night Stalkers, who were everybody's ride home. When the attack bogged down, the source went on, "in the heat of combat they saw their friends taking some casualties" so they "made a decision to go in and assist."

U.S. "advisors" entered the battle and turned it in favor of the Kurds. Approximately 70 prisoners were freed; reports varied on the exact number. Reports differ on how many of the freed prisoners were peshmerga. Foreign Policy reported that there were about 20 Iraqi soldiers, a few ISIS fighters thought to be traitors, and most of the rest Arab villagers from Hawijah who the ISIS fighters thought deserved killing.

This is the first operation we know of where ISIS fighters have been taken POW by U.S. forces. Army Times reported that "several" ISIS fighters were killed and five were "detained." When the Night Stalkers were in the air with the former prisoners and all allied soldiers accounted for, U.S. F-15s leveled the entire prison compound.

Allied losses were four peshmerga fighters wounded and Joshua Wheeler killed in action. By one account, the wall around the prison was breached with explosives and the U.S. troops were the first through the breach. It was at this point Wheeler fell.

He died in the fog of war, but his loss is clear in the Cherokee Nation. He leaves a wife, four sons, and an extended family including grandparents. Wheeler's sister, Rachel Quackenbush, told The New York Times about his return home after boot camp. Finding his siblings without food, he went out and shot a deer.

Most recently, Wheeler had been assigned to Army Special Operations Command at Ft. Bragg, North Carolina—the Cherokee historical homelands. He divided his down time between North Carolina and Oklahoma.

Cherokee Principal Chief Bill John Baker, in his role as mourner-in-chief, released a statement reading in part:

Our hearts go out to the Wheeler family for their tragic loss. Master Sergeant Joshua Wheeler was a highly decorated member of the Delta Force unit whose mission in Iraq was freeing hostages held by ISIS. Like so many of our Cherokee warriors, Joshua died serving our great country and we are forever indebted to him for his bravery and willingness to accept the most dangerous missions… Joshua is a true American hero and we will always honor his life and sacrifices at the Cherokee Nation.

Steve Russell10/26/15

=======

U.S. Soldier's Life, Recreated in Army, Ends in Combat

In a thinly populated, economically struggling patch of eastern Oklahoma, Joshua L. Wheeler had a difficult childhood and few options. The Army offered an escape, but it turned into much more. He made a career in uniform, becoming a highly decorated combat veteran in the elite and secretive Delta Force.

"In that area, if you didn't go to college, you basically had a choice of the oil fields or the military," said his uncle, Jack Shamblin. "The Army really suited him; he always had such robust energy and he always wanted to help people, and he felt he was doing that."

That protective instinct was evident from grade school when, as the oldest child in a dysfunctional home, he was often the one who made sure his siblings were clothed and fed. And it was on display on Thursday, when Master Sergeant Wheeler, 39, a father of four who was thinking of retiring from the Army, became the first American in four years to die in combat in Iraq.

That protective instinct was evident from grade school when, as the oldest child in a dysfunctional home, he was often the one who made sure his siblings were clothed and fed. And it was on display on Thursday, when Master Sergeant Wheeler, 39, a father of four who was thinking of retiring from the Army, became the first American in four years to die in combat in Iraq.

When Kurdish commandos went on a helicopter raid to rescue about 70 hostages who were about to be executed by Islamic State militants, the plan called for the Americans who accompanied them to offer support, not join in the action, Defense Secretary Ashton B. Carter said on Friday. But then the Kurdish attack on the prison where the hostages were held stalled, and Sergeant Wheeler responded.

"He ran to the sound of the guns," Mr. Carter said. "Obviously, we're very saddened that he lost his life," he said, adding, "I'm immensely proud of this young man."

A former Delta Force officer who had commanded Sergeant Wheeler in Iraq and had been briefed on the mission said that the Kurdish fighters, known as pesh merga, tried to blast a hole in the compound's outer wall, but could not. Sergeant Wheeler and another American, part of a team of 10 to 20 Delta Force operators who were present, ran up to the wall, breached it with explosives, and were the first ones through the hole.

"When you blow a hole in a compound wall, all the enemy fire gets directed toward that hole, and that is where he was," said the former officer, who spoke on condition of anonymity because he was not authorized to discuss the operation. The military does not officially acknowledge the existence of the Delta Force, the Army counterpart to Navy SEAL teams.

Aerial reconnaissance had shown a newly dug mass grave at the prison, and the hostages were to be killed on the morning of the raid, Mr. Carter said. "That location was planned to be an execution center."

The mission was a success, and the hostages were freed. A few of the pesh merga fighters were injured.

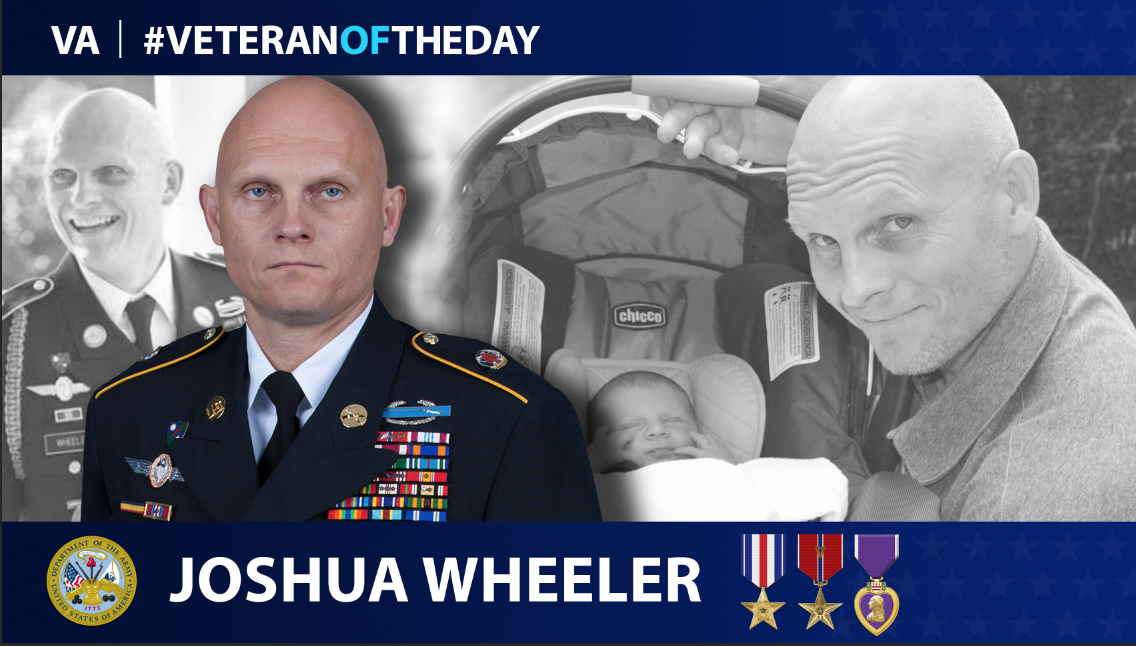

The only rescuer who died was Sergeant Wheeler, a veteran of 14 deployments to Iraq and Afghanistan, with a chest full of medals. His honors included four Bronze Stars with the letter V, awarded for valor in combat; and seven Bronze Stars, awarded for heroic or meritorious service in a combat zone. His body will be returned to the United States on Saturday.

He died far from his roots in Sequoyah County, Okla., just across the state border from Fort Smith, Ark.

His mother, Diane, had two marriages to troubled and abusive men, both ending in divorce, said Mr. Shamblin, her brother. She had two sons with her first husband and three daughters with her second, and outlived both men. She died last year at age 60.

One of Sergeant Wheeler's sisters, Rachel Quackenbush, said her parents were "mentally gone." Family members said that they often got by on some form of government assistance. Later in life, their mother, who was part Cherokee, like many people in the region, received help from the Cherokee nation.

It was her brother who held them together, making sure the younger children ate breakfast, got dressed and made it to school — even changing dirty diapers. On his own initiative, Mr. Shamblin said, he held a variety of jobs, including roofing and work on a blueberry farm, to bring in a few extra dollars.

Sergeant Wheeler's grandparents, now in their 80s, often took care of the children. "They were the only really stable influence," Mr. Shamblin said.

Ms. Quackenbush, 30, recalled one of her brother's first visits home from the military, when she was still a child. He noticed that the pantries were bare, retrieved a gun and left. "He went out and he shot a deer," she said. "He made us deer meat and cooked us dinner."

But at Muldrow High School, where he graduated in 1994, people saw no sign of the turmoil at home.

"He was always funny, even mischievous, but always the guy who seemed like he had your back," said April Isa, a classmate who now teaches English at the high school. "Most of our class was cliques, but he wasn't with just one group. He was friends with everyone."

Ron Flanagan, the Muldrow schools superintendent, was the assistant principal at the high school when Sergeant Wheeler attended classes there. "The thing I remember most clearly is that he was extremely respectful to everybody, classmates and teachers," he said. "He was a good kid who didn't get in any trouble."

Mr. Wheeler enlisted in 1995, and in 1997 he joined the Rangers, a specially trained group within the Army.

From 2004, he was assigned to Army Special Operations Command, based at Fort Bragg, N.C., which includes Delta Force, the extremely selective unit that carries out some of the military's riskiest operations. He completed specialized training in several fields, including parachute jumping, mountaineering, leading infantry units, explosives and urban combat.

"He was very focused, knew his job in and out," said the former officer who had commanded Sergeant Wheeler. "It is hard to describe these guys. They are taciturn, very introspective, but extremely competent. They are Jason Bournes, they really are."

He had three sons by his first marriage, which ended in divorce. He remarried in 2013, and he and his wife, Ashley, have an infant boy.

"He could never say much about where he went or what he did, but it was clear he loved it," Mr. Shamblin said. "And even after all that time in combat, there was such a kindness, a sweetness about him."

On visits home, either to Oklahoma or North Carolina, he focused on his boys and his extended family. Ms. Quackenbush said that when he would have to leave on another deployment, he would claim it was just for training, which she understood was untrue.

"He was exactly what was right about this world," she said. "He came from nothing and he really made something out of himself."

By RICHARD PÉREZ-PEÑA, KATIE ROGERS and DAVE PHILIPPS

Helene Cooper contributed reporting.

=======

http://www.soc.mil/Memorial%20Wall/Bios/wheeler_joshua.pdf

========

Wheeler, who joined the Army in 1995, was assigned to Headquarters, U.S. Army Special Operations Command at Fort Bragg, North Carolina.

====

ARMY TIMES

U.S. reports first death in combat with Islamic State

He is the first American service member killed in action by enemy fire while fighting Islamic State militants.

Wheeler, who was from Roland, Oklahoma, joined the Army as an infantryman. He served in the 75th Ranger Regiment, deploying three times to support combat operations in Iraq and Afghanistan, before being assigned to USASOC headquarters. He deployed 11 times after that to Iraq and Afghanistan, according to information released by USASOC.

Wheeler died from enemy gunfire near Hawijah, Iraq.

He was part of a team of dozens of U.S. special operations troops who joined Kurdish peshmerga fighters in a predawn raid of a detention facility run by the Islamic State group.

The U.S. and Kurdish forces killed several Islamic State militants and detained five others, defense officials have said.

In addition to Wheeler, four peshmerga soldiers were wounded.

The raid freed about 70 hostages whose lives officials said were in imminent danger.

=======

Joshua Wheeler: Cherokee Warrior, First US Casualty Fighting ISIS

Joshua L. Wheeler, 39-year-old Cherokee warrior, is the latest American lost in the fog of the second Iraq war, which is supposed to have ended. President George W. Bush announced the end of "major combat operations" in Iraq on May 1, 2003. President Barack Obama announced the end of "combat operations" in Iraq on August 31, 2010. President Bush, in the parlance of our times, "walked back" his claim later, and the video of President Obama's claim has been discreetly cleansed from the Whitehouse.gov website.

Master Sergeant Wheeler holds the distinction of being the first known U.S. casualty in the fight against ISIS. Since U.S. special operators are on the ground in several nations with which the U.S. is not at war working against ISIS, it is not clear that we the public would be told if one were killed in action. Because of the many people his life touched, Joshua Wheeler's loss is not one that could go unnoticed.

Sergeant Wheeler was career Army, assigned to the elite and secretive Delta Force. He joined the Army in 1995, the Rangers in 1997, and special ops in 2004. Because of the nature of his work, his family knew little, and we don't know as much as we otherwise might about his death. He was deployed 14 times that we know of and he received 11 Bronze Stars that we know of. In the special ops business, sometimes even honors are secret.

The details of the fight that took Sgt. Wheeler's life are not knowable with certainty through the fog, but the morality of the particular battle is.

Wheeler died fighting ISIS, the radical Islamist lunatics known for all the creative ways they kill hostages on video. Helpless prisoners who cannot resist have been beheaded, thrown off tall buildings, burned alive, drowned, and blown up by explosives. Video of these crimes comes from ISIS propaganda, not U.S. propaganda. Several battles have ended with videos of POWs being marched into waiting mass graves and executed by gunfire.

Yes, these are war crimes. This would be why they hide their faces more often than not. That's the morality of it. War crimes stand above any particular nation's interest and the duty to prevent them is clear in international law.

Wheeler died in a Delta Force raid on a facility holding ISIS prisoners near Hawijah in Northern Iraq. Human intelligence had predicted the prisoners were to be executed the next day and aerial reconnaissance showed a mass grave already dug.

The facility was thought to hold prisoners from the Kurdish peshmerga militia and we are told that the peshmerga had the lead in the operation. The Army's elite 160th Special Operations Aviation Regiment, known in the military as "Night Stalkers," airlifted Kurdish and U.S. soldiers to the ISIS prison near the witching hour. Special Forces say they "own the night."

One version of the encounter said the peshmerga were unable to breach the wall protecting the ISIS prison. Another version said the peshmerga came under fire that stalled their advance. Both could be true.

A U.S. military official gave Foreign Policy—which has in the past had very good sources—a simple explanation how the 30 or so special operators on the scene of a mission where their only role was "advise and support" got in a firefight.

"Support" was supposed to mean to protect the Night Stalkers, who were everybody's ride home. When the attack bogged down, the source went on, "in the heat of combat they saw their friends taking some casualties" so they "made a decision to go in and assist."

U.S. "advisors" entered the battle and turned it in favor of the Kurds. Approximately 70 prisoners were freed; reports varied on the exact number. Reports differ on how many of the freed prisoners were peshmerga. Foreign Policy reported that there were about 20 Iraqi soldiers, a few ISIS fighters thought to be traitors, and most of the rest Arab villagers from Hawijah who the ISIS fighters thought deserved killing.

This is the first operation we know of where ISIS fighters have been taken POW by U.S. forces. Army Times reported that "several" ISIS fighters were killed and five were "detained." When the Night Stalkers were in the air with the former prisoners and all allied soldiers accounted for, U.S. F-15s leveled the entire prison compound.

Allied losses were four peshmerga fighters wounded and Joshua Wheeler killed in action. By one account, the wall around the prison was breached with explosives and the U.S. troops were the first through the breach. It was at this point Wheeler fell.

He died in the fog of war, but his loss is clear in the Cherokee Nation. He leaves a wife, four sons, and an extended family including grandparents. Wheeler's sister, Rachel Quackenbush, told The New York Times about his return home after boot camp. Finding his siblings without food, he went out and shot a deer.

Most recently, Wheeler had been assigned to Army Special Operations Command at Ft. Bragg, North Carolina—the Cherokee historical homelands. He divided his down time between North Carolina and Oklahoma.

Cherokee Principal Chief Bill John Baker, in his role as mourner-in-chief, released a statement reading in part:

Our hearts go out to the Wheeler family for their tragic loss. Master Sergeant Joshua Wheeler was a highly decorated member of the Delta Force unit whose mission in Iraq was freeing hostages held by ISIS. Like so many of our Cherokee warriors, Joshua died serving our great country and we are forever indebted to him for his bravery and willingness to accept the most dangerous missions… Joshua is a true American hero and we will always honor his life and sacrifices at the Cherokee Nation.

Steve Russell10/26/15

=======

U.S. Soldier's Life, Recreated in Army, Ends in Combat

In a thinly populated, economically struggling patch of eastern Oklahoma, Joshua L. Wheeler had a difficult childhood and few options. The Army offered an escape, but it turned into much more. He made a career in uniform, becoming a highly decorated combat veteran in the elite and secretive Delta Force.

"In that area, if you didn't go to college, you basically had a choice of the oil fields or the military," said his uncle, Jack Shamblin. "The Army really suited him; he always had such robust energy and he always wanted to help people, and he felt he was doing that."

That protective instinct was evident from grade school when, as the oldest child in a dysfunctional home, he was often the one who made sure his siblings were clothed and fed. And it was on display on Thursday, when Master Sergeant Wheeler, 39, a father of four who was thinking of retiring from the Army, became the first American in four years to die in combat in Iraq.

That protective instinct was evident from grade school when, as the oldest child in a dysfunctional home, he was often the one who made sure his siblings were clothed and fed. And it was on display on Thursday, when Master Sergeant Wheeler, 39, a father of four who was thinking of retiring from the Army, became the first American in four years to die in combat in Iraq.

When Kurdish commandos went on a helicopter raid to rescue about 70 hostages who were about to be executed by Islamic State militants, the plan called for the Americans who accompanied them to offer support, not join in the action, Defense Secretary Ashton B. Carter said on Friday. But then the Kurdish attack on the prison where the hostages were held stalled, and Sergeant Wheeler responded.

"He ran to the sound of the guns," Mr. Carter said. "Obviously, we're very saddened that he lost his life," he said, adding, "I'm immensely proud of this young man."

A former Delta Force officer who had commanded Sergeant Wheeler in Iraq and had been briefed on the mission said that the Kurdish fighters, known as pesh merga, tried to blast a hole in the compound's outer wall, but could not. Sergeant Wheeler and another American, part of a team of 10 to 20 Delta Force operators who were present, ran up to the wall, breached it with explosives, and were the first ones through the hole.

"When you blow a hole in a compound wall, all the enemy fire gets directed toward that hole, and that is where he was," said the former officer, who spoke on condition of anonymity because he was not authorized to discuss the operation. The military does not officially acknowledge the existence of the Delta Force, the Army counterpart to Navy SEAL teams.

Aerial reconnaissance had shown a newly dug mass grave at the prison, and the hostages were to be killed on the morning of the raid, Mr. Carter said. "That location was planned to be an execution center."

The mission was a success, and the hostages were freed. A few of the pesh merga fighters were injured.

The only rescuer who died was Sergeant Wheeler, a veteran of 14 deployments to Iraq and Afghanistan, with a chest full of medals. His honors included four Bronze Stars with the letter V, awarded for valor in combat; and seven Bronze Stars, awarded for heroic or meritorious service in a combat zone. His body will be returned to the United States on Saturday.

He died far from his roots in Sequoyah County, Okla., just across the state border from Fort Smith, Ark.

His mother, Diane, had two marriages to troubled and abusive men, both ending in divorce, said Mr. Shamblin, her brother. She had two sons with her first husband and three daughters with her second, and outlived both men. She died last year at age 60.

One of Sergeant Wheeler's sisters, Rachel Quackenbush, said her parents were "mentally gone." Family members said that they often got by on some form of government assistance. Later in life, their mother, who was part Cherokee, like many people in the region, received help from the Cherokee nation.

It was her brother who held them together, making sure the younger children ate breakfast, got dressed and made it to school — even changing dirty diapers. On his own initiative, Mr. Shamblin said, he held a variety of jobs, including roofing and work on a blueberry farm, to bring in a few extra dollars.

Sergeant Wheeler's grandparents, now in their 80s, often took care of the children. "They were the only really stable influence," Mr. Shamblin said.

Ms. Quackenbush, 30, recalled one of her brother's first visits home from the military, when she was still a child. He noticed that the pantries were bare, retrieved a gun and left. "He went out and he shot a deer," she said. "He made us deer meat and cooked us dinner."

But at Muldrow High School, where he graduated in 1994, people saw no sign of the turmoil at home.

"He was always funny, even mischievous, but always the guy who seemed like he had your back," said April Isa, a classmate who now teaches English at the high school. "Most of our class was cliques, but he wasn't with just one group. He was friends with everyone."

Ron Flanagan, the Muldrow schools superintendent, was the assistant principal at the high school when Sergeant Wheeler attended classes there. "The thing I remember most clearly is that he was extremely respectful to everybody, classmates and teachers," he said. "He was a good kid who didn't get in any trouble."

Mr. Wheeler enlisted in 1995, and in 1997 he joined the Rangers, a specially trained group within the Army.

From 2004, he was assigned to Army Special Operations Command, based at Fort Bragg, N.C., which includes Delta Force, the extremely selective unit that carries out some of the military's riskiest operations. He completed specialized training in several fields, including parachute jumping, mountaineering, leading infantry units, explosives and urban combat.

"He was very focused, knew his job in and out," said the former officer who had commanded Sergeant Wheeler. "It is hard to describe these guys. They are taciturn, very introspective, but extremely competent. They are Jason Bournes, they really are."

He had three sons by his first marriage, which ended in divorce. He remarried in 2013, and he and his wife, Ashley, have an infant boy.

"He could never say much about where he went or what he did, but it was clear he loved it," Mr. Shamblin said. "And even after all that time in combat, there was such a kindness, a sweetness about him."

On visits home, either to Oklahoma or North Carolina, he focused on his boys and his extended family. Ms. Quackenbush said that when he would have to leave on another deployment, he would claim it was just for training, which she understood was untrue.

"He was exactly what was right about this world," she said. "He came from nothing and he really made something out of himself."

By RICHARD PÉREZ-PEÑA, KATIE ROGERS and DAVE PHILIPPS

Helene Cooper contributed reporting.

=======

http://www.soc.mil/Memorial%20Wall/Bios/wheeler_joshua.pdf

========

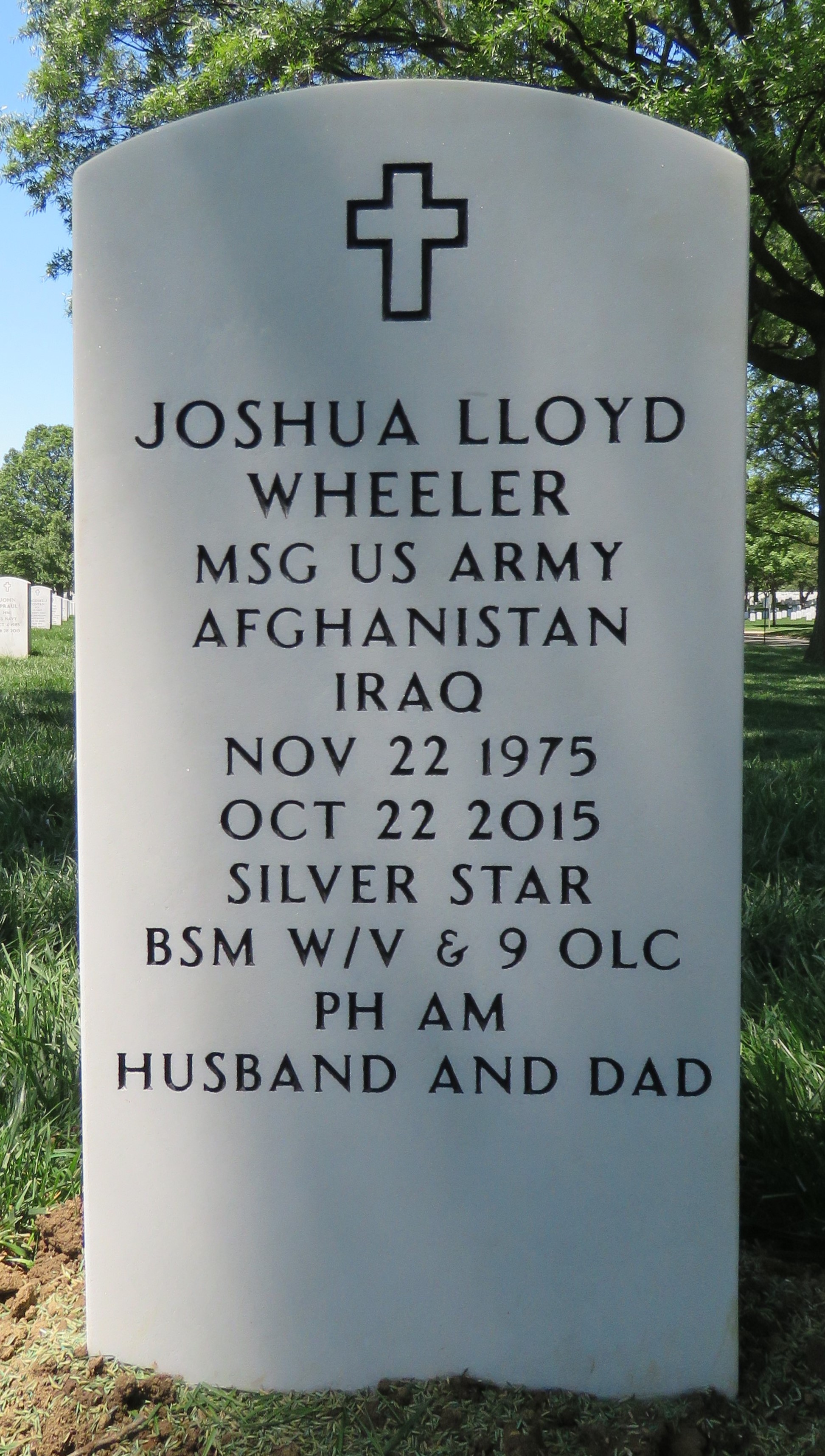

Inscription

MSG

US ARMY AFGHANISTAN ~ IRAQ

SILVER STAR

BSM W/V & 9 OLC

PH ~ AM

HUSBAND AND DAD