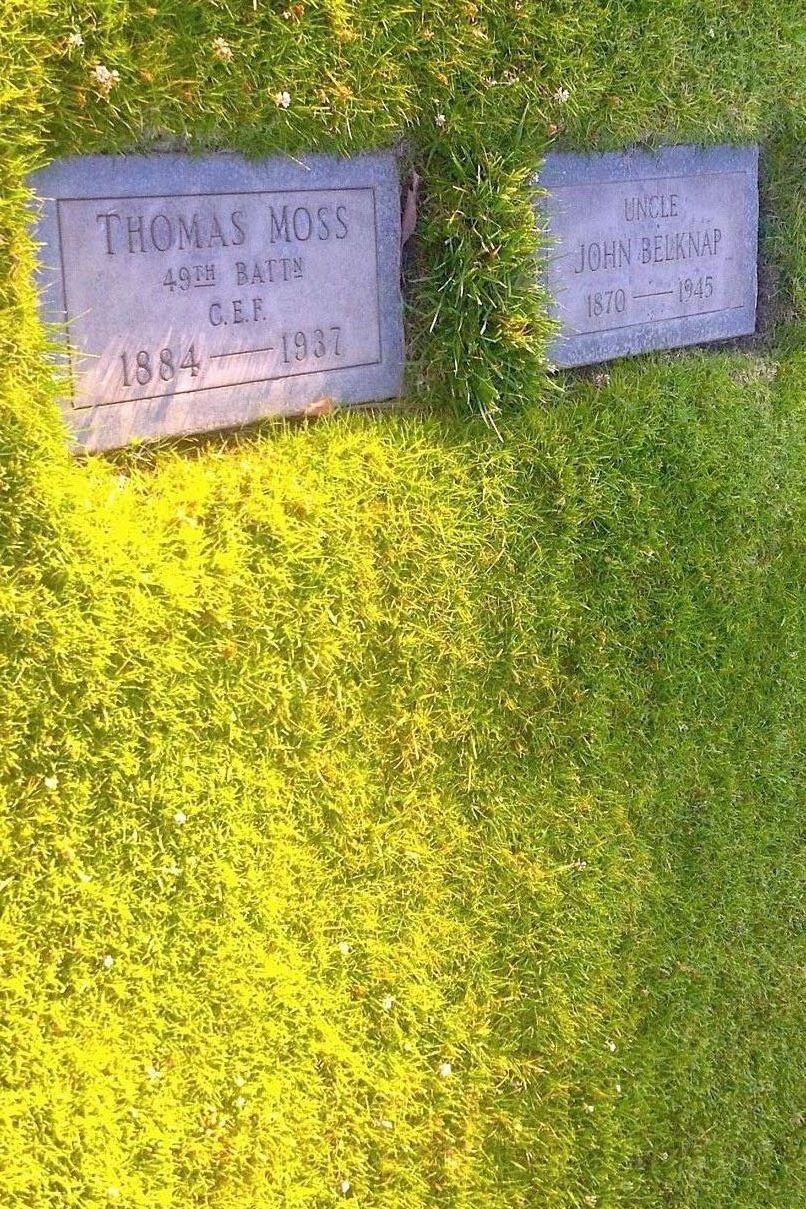

Editors note: Lucy's life was difficult to track after her divorce from James Douglas Hunter in Kalamazoo, MI. The breakthrough came from obtaining microfilm of the newspaper obituary of her mother, Myrta, which said she died at her farm home northwest of Paw Paw. That led me to research other living family members - namely Myrta's brother, John Smith Belknap. Sure enough, John showed up in the 1940 census living with his niece, Lucy Moss, in Santa Monica. That explains the significance of the second grave marker shown in the photo.

Lucy's patriotic fervor in the lead-up to America's entry into World War I was demonstrated by the play she produced with her students in the rural areas of St. Louis County, Minnesota. She followed through on that fervor by serving with the Red Cross in France during the war, where she met and married James Douglas Hunter. Later in 1936, she and her second husband, John Thomas Moss, traveled to Europe, likely drawn back to try to reconcile the traumatic events of her youth. Following is a transcription of the sketch that Lucy wrote, aimed at inspiring the poor immigrant families common in her school district to assist in the Red Cross effort.

SUNDAY MORNING – The Duluth News Tribune –DECEMBER 16, 1917

WAR SKETCH TELLS OF RURAL

AND COUNTRY RED CROSS WORK

Secretary at Headquarters Writes Play on Red Cross Organization and Influence.

The following stirring war sketch written by Miss Lucy Theodate Holmes, secretary at Red Cross Headquarters, was presented by her to the superintendent of schools and will be presented in every school in the county Dec 22. The sketch deals with the work of the Red Cross in the rural districts and especially touches upon the organization of the Junior Red Cross workers. It is here given in full:

“Cementing Home Ties”

By Lucy Theodate Holmes

(Mr. Buckland, a St. Louis county farmer; Mrs. Buckland, his wife; John Buckland, Helmi Buckland, Alvin Buckland and Andrew Buckland; their four children in order of age; Mrs. Toipoli, a neighbor and organizer for the Red Cross; and desired number of women, neighbors and friends of the Bucklands, who are Red Cross workers; (R.C.W., 1, 2, 3, 4, etc.).

SCENE I: Interior of rual homes, St Louis County, Minn. April, 1917. Mr. Buckland, a St. Louis county farmer, sits by the stove reading war news from a Finnish newspaper. His wife is setting the dinner table, while their three children, Helmi, Alvin and little Andrew play in one corcner at being soldiers.

Helmi—“I ought to be captain because I’m, the oldest. You give me that flag, Alvin.”

Alvin—“You? A girl be captain? No sir! And Andrew—you get the guns, Andrew—you’re Company B. Now get in line there, my fine fellows. Attention: Salute: No, you Helmi! Not with your left hand—that’s cause you’re a girl—who ever heard of a left-handed salute? Now, my men: Left—right—left—right forward march! Column right--column left,” (Drilling goes forward. Make this scene as amusing as possible: let children’s imagination play about kindling wood guns and make-believe lines of soldiers.)

Mrs. Buckland—(Looking up suddenly—angrily, from the bread she is cutting.) “Stop that noise, children—I don’t want you to play war—do you understand? We’ve got enough trouble already without playing at----”(Interrupted by rap at outside door.)

Mrs. Buckland—“Come in—Oh—it’s Mrs. Toipoli. Come in, neighbor.” (Mr. Buckland hands her his chair and stands, his back to the stove, with hands behind him.)

Mrs. Toipoli—“I came on an errand. Mrs. Buckland: you know so many of our boys around here have enlisted?”

Mrs. Buckland—(Bitterly—with emphasis) “Yes, I know.”

Mr. Buckland—(Uncertainly)—“Well, maybe they should, maybe they should, but my boy shall never go.”

Mrs. Toipoli—“Yes. I think they should my friends. I think they are fine fellows, doing their duty and I wish I had a son to lend to Uncle Sam. But I can work for my country and I will. I’m going to start a Red Cross society here in our community and I want you to help me.”

Alvin—(Very much interested, coming up to Mrs. Toipoli)—“Red Cross, Mrs. Toipoli? What’s that?”

Mrs. Toipoli—“That’s a wonderful organization of men and women, Alvin—for those who can’t really fight, you know—they think out ways to help here at home, and on the battlefield: nursing the wounded over there in France, making bandages and hospital clothes and warm, knitted things for the soldiers. We ought to get together and do that work here in our neighborhood. (Appealing to Mr. and Mrs. Buckland) Don’t you think so, good neighbors?”

Mrs. Buckland—(Suddenly, but with decision, while Mr. Buckland shakes his head in deep gloom)—“We have no money for such things, Mrs. Toipoli. We don’t believe in this war—it is making us very poor. Prices are going up. We can scarcely get enough to eat and to wear. We can save nothing. We cannot spend our money on your Red Cross society. Let the rich people do that.”

Mr. Buckland—“That’s right, that’s right, mother, times are hard—we don’t believe in this war. Our President promised to keep us out, and” (interrupted by hurried entrance of John, the oldest son. Children run happily to greet him.)

Andrew—“Did you get us candy in town, Johnny?”

Mrs. Buckland—Tut, these are hard times. Andy—don’t think of candy and such foolishness, my child.”

John—(Puts the children aside absently with his eyes on his mother.) “Mother! Father! I have enlisted!” (There is an electric second of silence before all start toward him with surprise and startled exclamations.)

Mrs. Buckland—“What? What? I forbid it! John, I forbid it! You shall not enter this turmoil of murder and waste!”

John—(Sadly, quietly)—“I am sorry, father and mother, but I think it is right to go. Do we not owe allegiance to this, our adopted country?”

Mrs. Buckland—(Angrily)—“Give our lives? Our children’s lives? No! We work for all we get in this country—we work hard--we give much in exchange for what we receive—“

John—“Yes, but you worked harder in Finland, and the Russians came with outrage and oppression and seized all that you earned. I’ve heard you tell it over and over, father. Here in this great, new country is freedom, opportunity—does the memory of freedom mean nothing to you now? Can you not be glad to have me go with the others to defend that freedom?”

Mrs. Buckland—(mutters)—“Tis a rich man’s war—let the men who are getting rich from munitions and graft and war-spoil send their sons to the murder.”

John—“Rich men’s sons? Hundreds of them! I have come, just now, from the recruiting station, father. They are there now—the sons of great wealth—enlisting—the army, the navy, both receive them every day.”

Mrs. Toipoli—(Coming over to lay a kind hand on John’s shoulder—whispers to him)—“Stand by it boy! You’re right! You’re right! I’m sorry for them (nodding sadly toward the stricken mother and father standing together in their anger and grief) but you must follow your own heart, John, and it tells you what is true.”

(Andrew, Alvin and Helmi have been moving toward their brother with large, anxious, fascinated eyes.)

Helmi—(Tenderly)—“I’ll knit for you, John—a sweater and socks and wristlets and a helmet and a scarf and a blanket----“

Alvin—(Breaking in)—“And here’s my knife, John—I’ll give it to you, to—to stab Germans” (Breathlessly).

(Little Andrew, seizing the flag that they had played with at soldier, comes toward John, with military bearing and short, soldierly steps. Saluting, he presents it to the big brother.)

John—“That’s right, little brother—that’s the best, the finest gift in all the world to a—to a soldier. It stands for the biggest thing just now—freedom! Democracy! (Bends over his little brother, with great tenderness. Then standing erect holds the flag at his right side. The father goes out with a loud angry banging of the door and two groups form themselves thus for the close of the scene):

Andrew facing John with hand up in salute; Helmi and Alvin on either side of them with their kindling wood guns at their sides, standing at attention; Mrs. Buckland drops into chair at table, burying her face in her hands, while Mrs. Tripoli stoops to comfort her. Suddenly John lifts the flag high in the air and all the children in the room, rising, sing “The Star Spangled Banner.”

SCENE II: The Buckland home a year later, April, 1918. Mrs. Buckland in Red Cross worker’s uniform, bends over table, cutting strips for wound pads. A group of neighbor women, also in Red Cross flowing caps and aprons, work about her, some knitting, some rolling head bandages, others cutting at a small table.

Mrs. Buckland—(With great sadness in her voice_--“It is nearly time for Neighbor Toipoli to return. Three months she has been away on the business of the Red Cross.”

First R.C.W.—“Yes, she will be home today; she will come here during the afternoon. How surprised she will be to find Red Cross headquarters at the Buckland house!”

Mrs. Buckland—“There are many surprises now-a-days. Yes, she will be surprised” (sadly).

Second R.C.W.—“Surprised and glad! This is a fine big place for us to meet, Mrs. Buckland. How many sets of dressings, now, Mrs. Kaminen?”

Mrs. Kaminen—(Pointing to a heap of wound pads on the table)—“This finishes 4,000 sets since December. I guess they will be useful in our hospitals.”

(Mr. Buckland enters bringing a large box.)

Mrs. Buckland—“From our neighbors at Riverboro—things for the Fench relief.”

(All the workers crowd around exclaiming in interest, as someone unpacks and holds up the things, little baby coats, warm little boys’ suits and baby dresses. 1. Little baby coats; 2. Warm little boys’ suits; 3. Such cunning baby dresses; 5. Scrap books for French orphans, and puzzle games for sick soldiers. Holds them up. The Buckland children have come into the room and are much interested in this array of articles. They seize the books and puzzles with great eagerness.)

Helmi—“Mother, we could make scrap books! Why can’t we help, too?”

Mrs. Buckland—(Thoughtfully) “You children? Well----”

Second R.C.W.—“Why that’s the very thing! They have organized the Junior Red Cross societies in the city schools. Why not have one here? Miss Pratt, the teacher, will help us.”

Fourth R.C.W.—“How many things they can make—my girls can sew—and –(a rap and Mrs. Toipoli enters and is greeted by everyone, pressing about her to shake her hand and ask rapid questions: 1. How is the work going? 2. Where have you succeeded? 3. When did you get back? She goes at once to Mrs. Buckland. “You have had great trouble, I hear, good friend. I am sorry. No news of your John since March?”

Mrs. Buckland—(Wipes her eyes and draws a letter from inside her dress)—“I keep it there—near my heart that is broken—it is the last time he wrote us. Three times his name has been published—missing.” (She turns away in an outburst of weeping.)

Mr. Buckland—(His hand on her arm to comfort her)—“We wish we had done more for him—for the cause—we can never, never forgive ourselves, Mrs. Toipoli.”

Mrs. Toipoli—(Comfortingly)—“But you are doing it now, dear friend, for some other brave boys—for your son John, perhaps—missing is not dead—you know.”

Mr. Buckland—“And you, Mrs. Toipoli? Have you had success on your journey?”

Mrs. Toipoli—“Five organizations have I started, my friends. One has only to tell these brave, new Americans the need and they fall to work. (Turning back to Mrs. Buckland) Let me see John’s letter, Mrs. Buckland. May I read it? Reads to herself, then aloud, while the workers, bent over their labors, gradually lift their heads to listen) Ah! Here he tells of the Red Cross in France. Christmas in the trenches! “We could hardly believe that Christmas Day had come. The Germans not 10 rods away have been bombarding us for nearly 20 hours. We dared not lift our heads above the sand bags until daylight came and the shots from our enemies ceased. Then, in a queer, dazed way we began crawling back to the dugouts and saying, “Merry Christmas” to each other, and trying to feel that it was Christmas. Your box hadn’t come then, Mother, and there was many another fellow wouldn’t have had a Christmas either if it hadn’t been for the Red Cross! God bless their workers! About 9 o’clock Sergeant Williams came cautiously crawling along to our dugout holding out two jolly looking packages to Bunkie and me—“Merry Christmas form the Red Cross.” There was a mighty useful khaki bag, Mother, with the little stars and stripes sewed tight to the front and it was stuffed with good things. Mother—you can’t think how we needed them all—a towel, soap—when had we seen any soap?—and socks! Goodness, how we needed a change. A game, a pipe and tobacco, candy and a Christmas card with greeting from the old United States. Mother, I wept, and I’m suspicious of Bunkie, too—behind that big, clean, new khaki handkerchief—well, the day wasn’t horrible any more—the dread of it was gone and we could talk about home and what you were all doing—and all the other Christmases as far, far back as we could remember. (Mrs. Toipoli translates the letter in Finnish as she goes along for those among the workers who do not speak English.) Oh, Mother, God bless the Red Cross and I hope you have one at home. I have seen the little starving, shivering orphans and I know their needs. God bless them, indeed.”

Mrs. Buckland—“Yes, God bless them—they helped our dear boy when we had done nothing to help. Now—it may be too late! Missing! Missing!” (Just then there is a shout, the door is flung open and John, the missing, rushes into the room—in khaki, brown and tattered and with the left sleeve hanging empty.) (Here the actors can invent their own exclamations and out-cries. Make scene as spontaneous with sensible, eager questions and exclamations as possible.) (Mrs. Buckland, overcome with joy and thankfulness hides her face in her hands. Her husband, with proud eyes on John, stands behind her. A silence falls on the exclaiming workers grouped about them and on the delighted children hugging his knees, as John begins to speak.)

John—“Yes ‘twas the Red Cross did it, Mother—it was a grim battle on the west front—in April, you know, you have read it all in the papers and somehow I got a bullet in the arm—there—(touching his sleeve) and my head knocked up. The last I can remember was crawling towards a stump with the idea of hiding from the Huns when they came back to look for the dead and wounded. I must have fallen right into the thing for one of the Red Cross scout dogs found me there—that was two days later—but it was weeks and weeks before I knew-knew where I was or anything. They operated, you know. Mother—there—(touches his head, laughing) and I guess I’m better than ever, and Oh, the tender care that brought me back to you, Mother! Yes, I owe them life and all—all that is left of me.”

Mrs. Buckland—(Dazedly)—They saved your life, John? They gave you back to us, John? The Red Cross?”

John—“Yes, Mother, and Oh, I’m proud to see you working like this—for them, and for the cause. There’s one good, strong, willing arm left, good neighbors (raises it high). I’ll use it as long as they need it; I’ll help you to work for them—the American Red Cross! God bless them forever!” (He seizes the flag that figured in the first scene and now rests behinds his picture and waves it high over his head, while actors, children and audience join, standing, in “America” as finale).

Editors note: Lucy's life was difficult to track after her divorce from James Douglas Hunter in Kalamazoo, MI. The breakthrough came from obtaining microfilm of the newspaper obituary of her mother, Myrta, which said she died at her farm home northwest of Paw Paw. That led me to research other living family members - namely Myrta's brother, John Smith Belknap. Sure enough, John showed up in the 1940 census living with his niece, Lucy Moss, in Santa Monica. That explains the significance of the second grave marker shown in the photo.

Lucy's patriotic fervor in the lead-up to America's entry into World War I was demonstrated by the play she produced with her students in the rural areas of St. Louis County, Minnesota. She followed through on that fervor by serving with the Red Cross in France during the war, where she met and married James Douglas Hunter. Later in 1936, she and her second husband, John Thomas Moss, traveled to Europe, likely drawn back to try to reconcile the traumatic events of her youth. Following is a transcription of the sketch that Lucy wrote, aimed at inspiring the poor immigrant families common in her school district to assist in the Red Cross effort.

SUNDAY MORNING – The Duluth News Tribune –DECEMBER 16, 1917

WAR SKETCH TELLS OF RURAL

AND COUNTRY RED CROSS WORK

Secretary at Headquarters Writes Play on Red Cross Organization and Influence.

The following stirring war sketch written by Miss Lucy Theodate Holmes, secretary at Red Cross Headquarters, was presented by her to the superintendent of schools and will be presented in every school in the county Dec 22. The sketch deals with the work of the Red Cross in the rural districts and especially touches upon the organization of the Junior Red Cross workers. It is here given in full:

“Cementing Home Ties”

By Lucy Theodate Holmes

(Mr. Buckland, a St. Louis county farmer; Mrs. Buckland, his wife; John Buckland, Helmi Buckland, Alvin Buckland and Andrew Buckland; their four children in order of age; Mrs. Toipoli, a neighbor and organizer for the Red Cross; and desired number of women, neighbors and friends of the Bucklands, who are Red Cross workers; (R.C.W., 1, 2, 3, 4, etc.).

SCENE I: Interior of rual homes, St Louis County, Minn. April, 1917. Mr. Buckland, a St. Louis county farmer, sits by the stove reading war news from a Finnish newspaper. His wife is setting the dinner table, while their three children, Helmi, Alvin and little Andrew play in one corcner at being soldiers.

Helmi—“I ought to be captain because I’m, the oldest. You give me that flag, Alvin.”

Alvin—“You? A girl be captain? No sir! And Andrew—you get the guns, Andrew—you’re Company B. Now get in line there, my fine fellows. Attention: Salute: No, you Helmi! Not with your left hand—that’s cause you’re a girl—who ever heard of a left-handed salute? Now, my men: Left—right—left—right forward march! Column right--column left,” (Drilling goes forward. Make this scene as amusing as possible: let children’s imagination play about kindling wood guns and make-believe lines of soldiers.)

Mrs. Buckland—(Looking up suddenly—angrily, from the bread she is cutting.) “Stop that noise, children—I don’t want you to play war—do you understand? We’ve got enough trouble already without playing at----”(Interrupted by rap at outside door.)

Mrs. Buckland—“Come in—Oh—it’s Mrs. Toipoli. Come in, neighbor.” (Mr. Buckland hands her his chair and stands, his back to the stove, with hands behind him.)

Mrs. Toipoli—“I came on an errand. Mrs. Buckland: you know so many of our boys around here have enlisted?”

Mrs. Buckland—(Bitterly—with emphasis) “Yes, I know.”

Mr. Buckland—(Uncertainly)—“Well, maybe they should, maybe they should, but my boy shall never go.”

Mrs. Toipoli—“Yes. I think they should my friends. I think they are fine fellows, doing their duty and I wish I had a son to lend to Uncle Sam. But I can work for my country and I will. I’m going to start a Red Cross society here in our community and I want you to help me.”

Alvin—(Very much interested, coming up to Mrs. Toipoli)—“Red Cross, Mrs. Toipoli? What’s that?”

Mrs. Toipoli—“That’s a wonderful organization of men and women, Alvin—for those who can’t really fight, you know—they think out ways to help here at home, and on the battlefield: nursing the wounded over there in France, making bandages and hospital clothes and warm, knitted things for the soldiers. We ought to get together and do that work here in our neighborhood. (Appealing to Mr. and Mrs. Buckland) Don’t you think so, good neighbors?”

Mrs. Buckland—(Suddenly, but with decision, while Mr. Buckland shakes his head in deep gloom)—“We have no money for such things, Mrs. Toipoli. We don’t believe in this war—it is making us very poor. Prices are going up. We can scarcely get enough to eat and to wear. We can save nothing. We cannot spend our money on your Red Cross society. Let the rich people do that.”

Mr. Buckland—“That’s right, that’s right, mother, times are hard—we don’t believe in this war. Our President promised to keep us out, and” (interrupted by hurried entrance of John, the oldest son. Children run happily to greet him.)

Andrew—“Did you get us candy in town, Johnny?”

Mrs. Buckland—Tut, these are hard times. Andy—don’t think of candy and such foolishness, my child.”

John—(Puts the children aside absently with his eyes on his mother.) “Mother! Father! I have enlisted!” (There is an electric second of silence before all start toward him with surprise and startled exclamations.)

Mrs. Buckland—“What? What? I forbid it! John, I forbid it! You shall not enter this turmoil of murder and waste!”

John—(Sadly, quietly)—“I am sorry, father and mother, but I think it is right to go. Do we not owe allegiance to this, our adopted country?”

Mrs. Buckland—(Angrily)—“Give our lives? Our children’s lives? No! We work for all we get in this country—we work hard--we give much in exchange for what we receive—“

John—“Yes, but you worked harder in Finland, and the Russians came with outrage and oppression and seized all that you earned. I’ve heard you tell it over and over, father. Here in this great, new country is freedom, opportunity—does the memory of freedom mean nothing to you now? Can you not be glad to have me go with the others to defend that freedom?”

Mrs. Buckland—(mutters)—“Tis a rich man’s war—let the men who are getting rich from munitions and graft and war-spoil send their sons to the murder.”

John—“Rich men’s sons? Hundreds of them! I have come, just now, from the recruiting station, father. They are there now—the sons of great wealth—enlisting—the army, the navy, both receive them every day.”

Mrs. Toipoli—(Coming over to lay a kind hand on John’s shoulder—whispers to him)—“Stand by it boy! You’re right! You’re right! I’m sorry for them (nodding sadly toward the stricken mother and father standing together in their anger and grief) but you must follow your own heart, John, and it tells you what is true.”

(Andrew, Alvin and Helmi have been moving toward their brother with large, anxious, fascinated eyes.)

Helmi—(Tenderly)—“I’ll knit for you, John—a sweater and socks and wristlets and a helmet and a scarf and a blanket----“

Alvin—(Breaking in)—“And here’s my knife, John—I’ll give it to you, to—to stab Germans” (Breathlessly).

(Little Andrew, seizing the flag that they had played with at soldier, comes toward John, with military bearing and short, soldierly steps. Saluting, he presents it to the big brother.)

John—“That’s right, little brother—that’s the best, the finest gift in all the world to a—to a soldier. It stands for the biggest thing just now—freedom! Democracy! (Bends over his little brother, with great tenderness. Then standing erect holds the flag at his right side. The father goes out with a loud angry banging of the door and two groups form themselves thus for the close of the scene):

Andrew facing John with hand up in salute; Helmi and Alvin on either side of them with their kindling wood guns at their sides, standing at attention; Mrs. Buckland drops into chair at table, burying her face in her hands, while Mrs. Tripoli stoops to comfort her. Suddenly John lifts the flag high in the air and all the children in the room, rising, sing “The Star Spangled Banner.”

SCENE II: The Buckland home a year later, April, 1918. Mrs. Buckland in Red Cross worker’s uniform, bends over table, cutting strips for wound pads. A group of neighbor women, also in Red Cross flowing caps and aprons, work about her, some knitting, some rolling head bandages, others cutting at a small table.

Mrs. Buckland—(With great sadness in her voice_--“It is nearly time for Neighbor Toipoli to return. Three months she has been away on the business of the Red Cross.”

First R.C.W.—“Yes, she will be home today; she will come here during the afternoon. How surprised she will be to find Red Cross headquarters at the Buckland house!”

Mrs. Buckland—“There are many surprises now-a-days. Yes, she will be surprised” (sadly).

Second R.C.W.—“Surprised and glad! This is a fine big place for us to meet, Mrs. Buckland. How many sets of dressings, now, Mrs. Kaminen?”

Mrs. Kaminen—(Pointing to a heap of wound pads on the table)—“This finishes 4,000 sets since December. I guess they will be useful in our hospitals.”

(Mr. Buckland enters bringing a large box.)

Mrs. Buckland—“From our neighbors at Riverboro—things for the Fench relief.”

(All the workers crowd around exclaiming in interest, as someone unpacks and holds up the things, little baby coats, warm little boys’ suits and baby dresses. 1. Little baby coats; 2. Warm little boys’ suits; 3. Such cunning baby dresses; 5. Scrap books for French orphans, and puzzle games for sick soldiers. Holds them up. The Buckland children have come into the room and are much interested in this array of articles. They seize the books and puzzles with great eagerness.)

Helmi—“Mother, we could make scrap books! Why can’t we help, too?”

Mrs. Buckland—(Thoughtfully) “You children? Well----”

Second R.C.W.—“Why that’s the very thing! They have organized the Junior Red Cross societies in the city schools. Why not have one here? Miss Pratt, the teacher, will help us.”

Fourth R.C.W.—“How many things they can make—my girls can sew—and –(a rap and Mrs. Toipoli enters and is greeted by everyone, pressing about her to shake her hand and ask rapid questions: 1. How is the work going? 2. Where have you succeeded? 3. When did you get back? She goes at once to Mrs. Buckland. “You have had great trouble, I hear, good friend. I am sorry. No news of your John since March?”

Mrs. Buckland—(Wipes her eyes and draws a letter from inside her dress)—“I keep it there—near my heart that is broken—it is the last time he wrote us. Three times his name has been published—missing.” (She turns away in an outburst of weeping.)

Mr. Buckland—(His hand on her arm to comfort her)—“We wish we had done more for him—for the cause—we can never, never forgive ourselves, Mrs. Toipoli.”

Mrs. Toipoli—(Comfortingly)—“But you are doing it now, dear friend, for some other brave boys—for your son John, perhaps—missing is not dead—you know.”

Mr. Buckland—“And you, Mrs. Toipoli? Have you had success on your journey?”

Mrs. Toipoli—“Five organizations have I started, my friends. One has only to tell these brave, new Americans the need and they fall to work. (Turning back to Mrs. Buckland) Let me see John’s letter, Mrs. Buckland. May I read it? Reads to herself, then aloud, while the workers, bent over their labors, gradually lift their heads to listen) Ah! Here he tells of the Red Cross in France. Christmas in the trenches! “We could hardly believe that Christmas Day had come. The Germans not 10 rods away have been bombarding us for nearly 20 hours. We dared not lift our heads above the sand bags until daylight came and the shots from our enemies ceased. Then, in a queer, dazed way we began crawling back to the dugouts and saying, “Merry Christmas” to each other, and trying to feel that it was Christmas. Your box hadn’t come then, Mother, and there was many another fellow wouldn’t have had a Christmas either if it hadn’t been for the Red Cross! God bless their workers! About 9 o’clock Sergeant Williams came cautiously crawling along to our dugout holding out two jolly looking packages to Bunkie and me—“Merry Christmas form the Red Cross.” There was a mighty useful khaki bag, Mother, with the little stars and stripes sewed tight to the front and it was stuffed with good things. Mother—you can’t think how we needed them all—a towel, soap—when had we seen any soap?—and socks! Goodness, how we needed a change. A game, a pipe and tobacco, candy and a Christmas card with greeting from the old United States. Mother, I wept, and I’m suspicious of Bunkie, too—behind that big, clean, new khaki handkerchief—well, the day wasn’t horrible any more—the dread of it was gone and we could talk about home and what you were all doing—and all the other Christmases as far, far back as we could remember. (Mrs. Toipoli translates the letter in Finnish as she goes along for those among the workers who do not speak English.) Oh, Mother, God bless the Red Cross and I hope you have one at home. I have seen the little starving, shivering orphans and I know their needs. God bless them, indeed.”

Mrs. Buckland—“Yes, God bless them—they helped our dear boy when we had done nothing to help. Now—it may be too late! Missing! Missing!” (Just then there is a shout, the door is flung open and John, the missing, rushes into the room—in khaki, brown and tattered and with the left sleeve hanging empty.) (Here the actors can invent their own exclamations and out-cries. Make scene as spontaneous with sensible, eager questions and exclamations as possible.) (Mrs. Buckland, overcome with joy and thankfulness hides her face in her hands. Her husband, with proud eyes on John, stands behind her. A silence falls on the exclaiming workers grouped about them and on the delighted children hugging his knees, as John begins to speak.)

John—“Yes ‘twas the Red Cross did it, Mother—it was a grim battle on the west front—in April, you know, you have read it all in the papers and somehow I got a bullet in the arm—there—(touching his sleeve) and my head knocked up. The last I can remember was crawling towards a stump with the idea of hiding from the Huns when they came back to look for the dead and wounded. I must have fallen right into the thing for one of the Red Cross scout dogs found me there—that was two days later—but it was weeks and weeks before I knew-knew where I was or anything. They operated, you know. Mother—there—(touches his head, laughing) and I guess I’m better than ever, and Oh, the tender care that brought me back to you, Mother! Yes, I owe them life and all—all that is left of me.”

Mrs. Buckland—(Dazedly)—They saved your life, John? They gave you back to us, John? The Red Cross?”

John—“Yes, Mother, and Oh, I’m proud to see you working like this—for them, and for the cause. There’s one good, strong, willing arm left, good neighbors (raises it high). I’ll use it as long as they need it; I’ll help you to work for them—the American Red Cross! God bless them forever!” (He seizes the flag that figured in the first scene and now rests behinds his picture and waves it high over his head, while actors, children and audience join, standing, in “America” as finale).

Gravesite Details

Lucy has no grave marker

Family Members

Sponsored by Ancestry

Advertisement

Records on Ancestry

Sponsored by Ancestry

Advertisement