Married Olive Carter Foss, 11 Feb 1857, Salt Lake City, Salt Lake, Utah

Children - Ezra Foss Woolley, Samuel Woolley, Edwin John Woolley, Samuel Woolley, Ida Foss Woolley, Eva Woolley, Effie Dean Woolley, Jedediah Foss Woolley, Franklin Benjamin Woolley

Married Artimecia Snow, 9 Apr 1868, Salt Lake City, Salt Lake, Utah

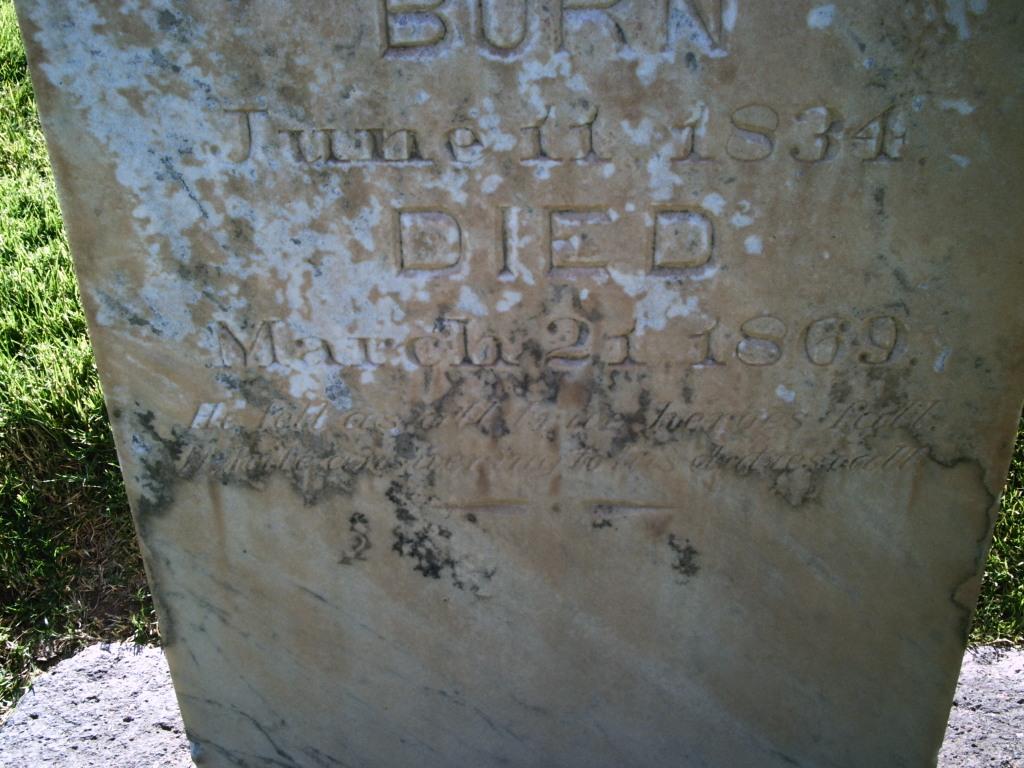

History - Franklin Benjamin Woolley was born June 11, 1834 in East Rochester, Columbiana County, Ohio, to Edwin Dilworth Woolley and Mary Wickersham. His parents, who were Quakers, joined the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints when Franklin was about five years old.

Franklin was the oldest of eight children. Three children, however, died in infancy. His parents took their family and gathered with the Saints in Quincy, Illinois, where the members sought refuge after being run out of Missouri by mobs. Franklin was a child when Nauvoo was being built. He had his share of malaria and sickness with the rest of the Saints. He recalls the poverty of those days:

“I recollect feeling very sorry for the people who were in such destitute circumstances, many families who had no shelter from the storms of winter and the rains of Spring than rails split and laid up in a square, with a few patched and ragged quilts hung up at the sides to partially break the force of the cold winds of winter.”

His father set up a merchandising establishment in Nauvoo. His father was better off than most people because he had not lost everything in Missouri like the others. Later they lived in a very fine brick home while in Nauvoo.

Franklin was ten years old when the Prophet Joseph Smith was killed by a mob at Carthage. He remembered when he went to see the dead bodies of Joseph and his brother Hyrum:

“Though I was quite young yet I felt, when I saw him extended upon his bier lifeless and cold, a desire to aid in avenging his death, upon our ruthless persecutors. Great excitement prevailed for a time, but by the judicious management of the leading men of the church it was kept in proper bounds and good resulted from all.”

Sidney Rigdon tried to take control of the church, but at a meeting where Brigham Young stood up, Brigham looked and spoke like Joseph Smith. It was a sign to the saints that control of the church should remain with the apostles. “Before another year was out there would be fifteen splinter groups going to five states. Franklin wrote, ‘The weak and wavering were overcome and departed from the faith.’ But far more than a majority remained loyal to the apostles.”

The building of the temple was hastened. Mobs began persecuting saints in outlying areas causing them to move into Nauvoo. The city began to make ready for a trek west. Wagons were built and supplies were sought. Rumors started that the government was going to move in to disarm the Mormons. The temple was finished the beginning of December and hundreds received their endowments and were sealed to their families. Franklin’s family had more than they could handle with everyone trying to get supplies from their store. Finally the first group headed out across the river, while the Woolleys stayed behind to help others get ready.

Franklin related, “the early companies commenced their toilsome journey through the storms and snow and rain at that inclement season of the year, sharing in the dangers and exposures incident to such a march with no shelter but the frail covers of their wagons, no hospitable roof to receive them at night and shield them from the drenching rain or the merciless pitting of the frozen snows. The road was marked by the graves of the sufferers.”

Franklin said, the Woolleys closed their stores in the “for part of March to get ready to move in the spring. My father took several loads of furniture, beds , etc. into the country around, and sold them at merely nominal prices, as we were forced to leave them behind us.”

“Many Saints had been obliged to go ‘without realizing one cent for their dwellings,’ but Edwin had better fortune. ‘We sold 30 acres of good farming land; well fenced and under cultivation for two yokes of cattle and an old wagon, altogether worth less than a hundred dollars.”

“At last in early June the Woolleys crossed the Mississippi. By themselves they formed a small wagon train, for they included the fifteen members of Edwin’s immediate family. They left behind a near-empty city.”

“Young Franklin did not ride in the wagons, but was kept busy ‘driving the loose cattle, which duty with some slight interruptions owing to illness I performed until we overtook the main body of the people.’”

“’We got to the eastern bank of the Missouri river at Council Bluffs the fore part of August,’ wrote John. The Woolleys had missed the departure of the Mormon Battalion volunteers by two weeks. John, Samuel, or young John would surely have been obligated to enlist had the family arrived a week or two earlier. But now the Woolley men would have to be shared with the temporary widows and orphans of the camp.”

“A thousand wagons ‘camped on three hills which had springs of water between them.’ Tents, too, were scattered over the hills, ‘and when the camp fires are lit at night it is a beautiful sight,’ wrote Mary Lightner. ‘It makes me think how the children of Israel’s camp must have looked in the days of Moses when journeying the wilderness.’”

“Brigham Young blocked out Winter Quarters, and the men helped to gather and stack grass for the cattle during the winter. Edwin was asked to go to St. Louis to purchase some more goods with the Mormon soldiers’ wages. Meanwhile Franklin helped cut logs for a family cabin.

When his father came home six weeks later they raised a medium sized cabin for the Woolley family that had a sod chimney, and a roof of oak ‘shakes’ secured with weight poles without the additional protective layer of wood shingles. He was lucky to have a loft and two six paned windows. Four-inch cracks between the wall timbers were ‘mudded up’ with clay. For a time they lived with a floor of tamped dirt kept clean by a little straw spread about. The Woolleys considered themselves fortunate compared to the dugout dwellers whose walls were cut out of the ground and whose roofs were logs covered with cloth and sod.”

“So that none would starve outright, ‘the whole went on half or quarter rations.’ The problem was not lack of bulk but of variety. They had plenty of parched cornmeal, but they lacked vegetables, except potatoes. Scurvy set in. John’s father-in-law died of it in October. The Woolleys dried apples may have saved them from it. During the winter of 1846-47 (Sept. to June), 222 persons died at or near Winter Quarters.”

“On January 17 Brigham announced a revelation (D&C 136) to a gathering at Winter Quarters. The healthy should outfit the pioneers to go in the spring while others should stay behind to plant crops and help those who follow. Edwin was one of those mentioned who were to ‘remain behind this season.’ He was to keep Winter Quarter supplied with goods by operating a store.”

“It was a gloomy for those who stayed behind. ‘When one meal was eaten, how the next was to be obtained was something of a puzzle.’ That was one of the reasons for his second trip to St. Louis.”

“A general conference was held in Council Bluffs that winter at which Brigham Young was sustained as President of the Church.”

“Another hard winter followed. Even in privation children’s education was attended to: ‘I attended one most of the Winter,’ wrote Franklin, ‘and father also had private school at his home. I attended a day school this winter but made little progress in my studies, but upon the whole we passed a pleasant winter.’”

“With spring coming, in anticipation of the ‘Great migration to the Valley’ of 1848 everyone in Winter Quarters ‘that could possibly raise means enough for an outfit, strained every nerve to accomplish the object. Brigham Young and Heber Kimball would lead the largest migration, Willard Richards would follow with a small division several weeks later, and during the summer eight more companies would cross the Great Plains.”

See Edwin Dilworth’s life story for their trek across the plains. Franklin’s main chore was driving and keeping track of the cattle. One time some Indians came when he was watching the cows. Some other kids ran back to get some of the men, but Franklin stood his ground. He did not want them to be stolen. Luckily some men came riding up on horseback, and the Indians rode off. It must have been frightening to a young boy.

When they arrived in Salt Lake Valley, Samuel (Franklin’s Uncle) had problems keeping track of his cattle. Franklin “having his father’s eye for business opportunity, shortly went to Uncle Samuel and ‘made a bargain’ to guard his cattle. For two or three cents per animal he would lead a herd to the common pasture southwest of the city, bringing in the animals each night.”

The Woolley men cut many logs up Cotton Wood Canyon to build their homes. Many tried to make adobe bricks. First attempts didn’t do too well, but they soon became professional at it and early Salt Lake City became an adobe town. The Woolley home was partly logs and partly adobe.

The Saints struggled with early frost that killed some crops. Then there were the crickets which destroyed a lot of wheat and corn. Neighbors swapped garden produce. Bartering was the major exchange. Saw mills and gristmills were established. There was plenty of work to do.

Their first winter was not very pleasant according to Franklin who remembered the three-room house as ‘very cold and uncomfortable’ during this unusually bitter winter. The first great snowstorm of the year struck December 12 and 13, after which the roof leaked muddy streamlets of water and the women cooked under umbrellas. ‘We were often obliged to cut the ice with an axe to enable us to shut the door.’”

Schools were set up, sometimes in a tent. The men had meetings to form a government. Brigham Young was elected governor. Church meetings took quite a bit of time on Sundays.

In order to combat the dreariness of life, dances were held. The partying was necessary to hold off homesickness. “Brigham Young thought the partying was wholesome; it exercised his body and cleared the mind. Mormon dancing was ‘not languid, done-up style that polite Europe affects: ‘positions’ were maintained, steps were elaborately executed, and somewhat severe muscular exercise was the result. Waltzing, with its body contact, was seldom allowed; these were country dances—‘a common movement, such as swaying or stamping, done by a group of men and women to the accompaniment of rhythm, cries and handclappings.’ Polkas were suspect, but a quadrille, Scottish reel, or minuet was quite appropriate.”

“The Woolleys celebrated Christmas with an all-night party at Samuel’s cabin. Catherine had prepared for five days. She had meat pies, roast chicken, and a Christmas goose.”

The next couple of years were very meager. The cattle didn’t have enough to eat and many died.

Finally Brigham Young had everyone report on their food supplies and established rations. Whooping cough and other illnesses set in. Priesthood blessings were used frequently. Samuel suffered from a toothache all one winter. The men began to establish irrigation and canal systems. They lacked experience in this area and had to learn as they went along. Edwin and his sons were able to get a better roof on their home.

When not in the fields, they “worked for others ‘to obtain a few pounds of butter or cheese, or shorts or whatever we could get that would assist us till the expected harvest time should arrive.’ Edwin worked at ditching for $1.50 a day. When at last the spring harvest came, crickets and grasshoppers and drought again took much of the crop. But ‘we had enough left to sustain us for another year for which we give thanks.’”

Franklin’s father was asked to make a trip back east to purchase goods. His father was gone for a year. This left a lot of burden on Franklin and his older brother, John, to help tend the family and farm. His two Uncles were also there to help. Edwin brought back Louisa’s son (she died), and married Ann Olpin who Edwin engaged to take care of the child.

Now having many goods to sell, Franklin’s family began to prosper. While his father was spent much time in the store, Franklin was expected to help a lot with the farm work.

Franklin married Olive Carter Foss on Feb. 11, 1857. As his father became more involved in the territorial legislature, Brigham Young’s business manager, and Bishop of the Thirteenth ward, Franklin was called upon more and more to help with the family store and other responsibilities that his father could not attend to.

June 8, 1861 Franklin joined three hundred families called to settle Utah’s Dixie.

In January 1867 a domestic telegraph system was completed connecting Logan to St. George. “Erection of the telegraph was complicated by Indian disturbances in the southern settlements, which were essentially a reaction to bolder and broader usurpation of Indian lands. When Frank had settled the St. George valley in 1861, the Mormons had made their own agreements with Indians on the use of lands. Not until 1865 did the federal government sign a treaty with the Indians, providing reservations for them and assuming title to territorial lands.”

“Government ownership of the lands was welcomed by most Indians, except for a band of several hundred rebels led by a young warrior, Black Hawk. For four years, 1865 through 1868, Black Hawk waged a guerrilla war against the Mormons, forcing the abandonment of twenty-five settlements and killing seventy white men. In 1866 the Nauvoo Legion was mustered to fight back. Among the Salt Lake City men called to fight were Samuel’s oldest son, Samuel Henry, and Edwin’s sons Frank, Dee (E.D., Jr.), and Dub (Gordon).”

“By 1867 the war had calmed. Franklin remained in St. George, where he became purchasing agent for the Southern Utah Co-operative Mercantile Association, formed to bring goods to Utah’s Dixie during the months that trails were not open from the East and at a cost lower than gentile freighters charged.”

“On the morning of April 12, 1869, Edwin received a letter from the commission merchant, James Linforth in San Francisco, that ‘a Mr. Woolley, who had a train laden with $20,000 worth of goods en route for Utah, was murdered by the Piute Indians’ on the Mojave River between San Bernardino and St. George.”

Franklin was an incredible support to his family during all the struggles to join this new religion, travel west, and build a life out of the wilderness. His contribution was so important to the taming of the west and the establishment of Zion. His death by Indians demonstrated the kind of hardships and opposition that the saints met on every side in building up the kingdom of God in the latter-days.

All information above is taken from From Quaker to Latter-Day Saint, Edwin Dilworth Woolley, by Leonard J. Arrington, Deseret Book Co. 1976.

Married Olive Carter Foss, 11 Feb 1857, Salt Lake City, Salt Lake, Utah

Children - Ezra Foss Woolley, Samuel Woolley, Edwin John Woolley, Samuel Woolley, Ida Foss Woolley, Eva Woolley, Effie Dean Woolley, Jedediah Foss Woolley, Franklin Benjamin Woolley

Married Artimecia Snow, 9 Apr 1868, Salt Lake City, Salt Lake, Utah

History - Franklin Benjamin Woolley was born June 11, 1834 in East Rochester, Columbiana County, Ohio, to Edwin Dilworth Woolley and Mary Wickersham. His parents, who were Quakers, joined the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints when Franklin was about five years old.

Franklin was the oldest of eight children. Three children, however, died in infancy. His parents took their family and gathered with the Saints in Quincy, Illinois, where the members sought refuge after being run out of Missouri by mobs. Franklin was a child when Nauvoo was being built. He had his share of malaria and sickness with the rest of the Saints. He recalls the poverty of those days:

“I recollect feeling very sorry for the people who were in such destitute circumstances, many families who had no shelter from the storms of winter and the rains of Spring than rails split and laid up in a square, with a few patched and ragged quilts hung up at the sides to partially break the force of the cold winds of winter.”

His father set up a merchandising establishment in Nauvoo. His father was better off than most people because he had not lost everything in Missouri like the others. Later they lived in a very fine brick home while in Nauvoo.

Franklin was ten years old when the Prophet Joseph Smith was killed by a mob at Carthage. He remembered when he went to see the dead bodies of Joseph and his brother Hyrum:

“Though I was quite young yet I felt, when I saw him extended upon his bier lifeless and cold, a desire to aid in avenging his death, upon our ruthless persecutors. Great excitement prevailed for a time, but by the judicious management of the leading men of the church it was kept in proper bounds and good resulted from all.”

Sidney Rigdon tried to take control of the church, but at a meeting where Brigham Young stood up, Brigham looked and spoke like Joseph Smith. It was a sign to the saints that control of the church should remain with the apostles. “Before another year was out there would be fifteen splinter groups going to five states. Franklin wrote, ‘The weak and wavering were overcome and departed from the faith.’ But far more than a majority remained loyal to the apostles.”

The building of the temple was hastened. Mobs began persecuting saints in outlying areas causing them to move into Nauvoo. The city began to make ready for a trek west. Wagons were built and supplies were sought. Rumors started that the government was going to move in to disarm the Mormons. The temple was finished the beginning of December and hundreds received their endowments and were sealed to their families. Franklin’s family had more than they could handle with everyone trying to get supplies from their store. Finally the first group headed out across the river, while the Woolleys stayed behind to help others get ready.

Franklin related, “the early companies commenced their toilsome journey through the storms and snow and rain at that inclement season of the year, sharing in the dangers and exposures incident to such a march with no shelter but the frail covers of their wagons, no hospitable roof to receive them at night and shield them from the drenching rain or the merciless pitting of the frozen snows. The road was marked by the graves of the sufferers.”

Franklin said, the Woolleys closed their stores in the “for part of March to get ready to move in the spring. My father took several loads of furniture, beds , etc. into the country around, and sold them at merely nominal prices, as we were forced to leave them behind us.”

“Many Saints had been obliged to go ‘without realizing one cent for their dwellings,’ but Edwin had better fortune. ‘We sold 30 acres of good farming land; well fenced and under cultivation for two yokes of cattle and an old wagon, altogether worth less than a hundred dollars.”

“At last in early June the Woolleys crossed the Mississippi. By themselves they formed a small wagon train, for they included the fifteen members of Edwin’s immediate family. They left behind a near-empty city.”

“Young Franklin did not ride in the wagons, but was kept busy ‘driving the loose cattle, which duty with some slight interruptions owing to illness I performed until we overtook the main body of the people.’”

“’We got to the eastern bank of the Missouri river at Council Bluffs the fore part of August,’ wrote John. The Woolleys had missed the departure of the Mormon Battalion volunteers by two weeks. John, Samuel, or young John would surely have been obligated to enlist had the family arrived a week or two earlier. But now the Woolley men would have to be shared with the temporary widows and orphans of the camp.”

“A thousand wagons ‘camped on three hills which had springs of water between them.’ Tents, too, were scattered over the hills, ‘and when the camp fires are lit at night it is a beautiful sight,’ wrote Mary Lightner. ‘It makes me think how the children of Israel’s camp must have looked in the days of Moses when journeying the wilderness.’”

“Brigham Young blocked out Winter Quarters, and the men helped to gather and stack grass for the cattle during the winter. Edwin was asked to go to St. Louis to purchase some more goods with the Mormon soldiers’ wages. Meanwhile Franklin helped cut logs for a family cabin.

When his father came home six weeks later they raised a medium sized cabin for the Woolley family that had a sod chimney, and a roof of oak ‘shakes’ secured with weight poles without the additional protective layer of wood shingles. He was lucky to have a loft and two six paned windows. Four-inch cracks between the wall timbers were ‘mudded up’ with clay. For a time they lived with a floor of tamped dirt kept clean by a little straw spread about. The Woolleys considered themselves fortunate compared to the dugout dwellers whose walls were cut out of the ground and whose roofs were logs covered with cloth and sod.”

“So that none would starve outright, ‘the whole went on half or quarter rations.’ The problem was not lack of bulk but of variety. They had plenty of parched cornmeal, but they lacked vegetables, except potatoes. Scurvy set in. John’s father-in-law died of it in October. The Woolleys dried apples may have saved them from it. During the winter of 1846-47 (Sept. to June), 222 persons died at or near Winter Quarters.”

“On January 17 Brigham announced a revelation (D&C 136) to a gathering at Winter Quarters. The healthy should outfit the pioneers to go in the spring while others should stay behind to plant crops and help those who follow. Edwin was one of those mentioned who were to ‘remain behind this season.’ He was to keep Winter Quarter supplied with goods by operating a store.”

“It was a gloomy for those who stayed behind. ‘When one meal was eaten, how the next was to be obtained was something of a puzzle.’ That was one of the reasons for his second trip to St. Louis.”

“A general conference was held in Council Bluffs that winter at which Brigham Young was sustained as President of the Church.”

“Another hard winter followed. Even in privation children’s education was attended to: ‘I attended one most of the Winter,’ wrote Franklin, ‘and father also had private school at his home. I attended a day school this winter but made little progress in my studies, but upon the whole we passed a pleasant winter.’”

“With spring coming, in anticipation of the ‘Great migration to the Valley’ of 1848 everyone in Winter Quarters ‘that could possibly raise means enough for an outfit, strained every nerve to accomplish the object. Brigham Young and Heber Kimball would lead the largest migration, Willard Richards would follow with a small division several weeks later, and during the summer eight more companies would cross the Great Plains.”

See Edwin Dilworth’s life story for their trek across the plains. Franklin’s main chore was driving and keeping track of the cattle. One time some Indians came when he was watching the cows. Some other kids ran back to get some of the men, but Franklin stood his ground. He did not want them to be stolen. Luckily some men came riding up on horseback, and the Indians rode off. It must have been frightening to a young boy.

When they arrived in Salt Lake Valley, Samuel (Franklin’s Uncle) had problems keeping track of his cattle. Franklin “having his father’s eye for business opportunity, shortly went to Uncle Samuel and ‘made a bargain’ to guard his cattle. For two or three cents per animal he would lead a herd to the common pasture southwest of the city, bringing in the animals each night.”

The Woolley men cut many logs up Cotton Wood Canyon to build their homes. Many tried to make adobe bricks. First attempts didn’t do too well, but they soon became professional at it and early Salt Lake City became an adobe town. The Woolley home was partly logs and partly adobe.

The Saints struggled with early frost that killed some crops. Then there were the crickets which destroyed a lot of wheat and corn. Neighbors swapped garden produce. Bartering was the major exchange. Saw mills and gristmills were established. There was plenty of work to do.

Their first winter was not very pleasant according to Franklin who remembered the three-room house as ‘very cold and uncomfortable’ during this unusually bitter winter. The first great snowstorm of the year struck December 12 and 13, after which the roof leaked muddy streamlets of water and the women cooked under umbrellas. ‘We were often obliged to cut the ice with an axe to enable us to shut the door.’”

Schools were set up, sometimes in a tent. The men had meetings to form a government. Brigham Young was elected governor. Church meetings took quite a bit of time on Sundays.

In order to combat the dreariness of life, dances were held. The partying was necessary to hold off homesickness. “Brigham Young thought the partying was wholesome; it exercised his body and cleared the mind. Mormon dancing was ‘not languid, done-up style that polite Europe affects: ‘positions’ were maintained, steps were elaborately executed, and somewhat severe muscular exercise was the result. Waltzing, with its body contact, was seldom allowed; these were country dances—‘a common movement, such as swaying or stamping, done by a group of men and women to the accompaniment of rhythm, cries and handclappings.’ Polkas were suspect, but a quadrille, Scottish reel, or minuet was quite appropriate.”

“The Woolleys celebrated Christmas with an all-night party at Samuel’s cabin. Catherine had prepared for five days. She had meat pies, roast chicken, and a Christmas goose.”

The next couple of years were very meager. The cattle didn’t have enough to eat and many died.

Finally Brigham Young had everyone report on their food supplies and established rations. Whooping cough and other illnesses set in. Priesthood blessings were used frequently. Samuel suffered from a toothache all one winter. The men began to establish irrigation and canal systems. They lacked experience in this area and had to learn as they went along. Edwin and his sons were able to get a better roof on their home.

When not in the fields, they “worked for others ‘to obtain a few pounds of butter or cheese, or shorts or whatever we could get that would assist us till the expected harvest time should arrive.’ Edwin worked at ditching for $1.50 a day. When at last the spring harvest came, crickets and grasshoppers and drought again took much of the crop. But ‘we had enough left to sustain us for another year for which we give thanks.’”

Franklin’s father was asked to make a trip back east to purchase goods. His father was gone for a year. This left a lot of burden on Franklin and his older brother, John, to help tend the family and farm. His two Uncles were also there to help. Edwin brought back Louisa’s son (she died), and married Ann Olpin who Edwin engaged to take care of the child.

Now having many goods to sell, Franklin’s family began to prosper. While his father was spent much time in the store, Franklin was expected to help a lot with the farm work.

Franklin married Olive Carter Foss on Feb. 11, 1857. As his father became more involved in the territorial legislature, Brigham Young’s business manager, and Bishop of the Thirteenth ward, Franklin was called upon more and more to help with the family store and other responsibilities that his father could not attend to.

June 8, 1861 Franklin joined three hundred families called to settle Utah’s Dixie.

In January 1867 a domestic telegraph system was completed connecting Logan to St. George. “Erection of the telegraph was complicated by Indian disturbances in the southern settlements, which were essentially a reaction to bolder and broader usurpation of Indian lands. When Frank had settled the St. George valley in 1861, the Mormons had made their own agreements with Indians on the use of lands. Not until 1865 did the federal government sign a treaty with the Indians, providing reservations for them and assuming title to territorial lands.”

“Government ownership of the lands was welcomed by most Indians, except for a band of several hundred rebels led by a young warrior, Black Hawk. For four years, 1865 through 1868, Black Hawk waged a guerrilla war against the Mormons, forcing the abandonment of twenty-five settlements and killing seventy white men. In 1866 the Nauvoo Legion was mustered to fight back. Among the Salt Lake City men called to fight were Samuel’s oldest son, Samuel Henry, and Edwin’s sons Frank, Dee (E.D., Jr.), and Dub (Gordon).”

“By 1867 the war had calmed. Franklin remained in St. George, where he became purchasing agent for the Southern Utah Co-operative Mercantile Association, formed to bring goods to Utah’s Dixie during the months that trails were not open from the East and at a cost lower than gentile freighters charged.”

“On the morning of April 12, 1869, Edwin received a letter from the commission merchant, James Linforth in San Francisco, that ‘a Mr. Woolley, who had a train laden with $20,000 worth of goods en route for Utah, was murdered by the Piute Indians’ on the Mojave River between San Bernardino and St. George.”

Franklin was an incredible support to his family during all the struggles to join this new religion, travel west, and build a life out of the wilderness. His contribution was so important to the taming of the west and the establishment of Zion. His death by Indians demonstrated the kind of hardships and opposition that the saints met on every side in building up the kingdom of God in the latter-days.

All information above is taken from From Quaker to Latter-Day Saint, Edwin Dilworth Woolley, by Leonard J. Arrington, Deseret Book Co. 1976.

Family Members

-

![]()

John Wickersham Woolley

1831–1928

-

![]()

Rachel Emma Woolley Simmons

1836–1926

-

![]()

Samuel Wickersham Woolley

1840–1908

-

![]()

Henrietta Woolley Simmons

1843–1911

-

![]()

Edwin Dilworth Woolley Jr

1845–1920

-

![]()

Mary Louisa Woolley Clark

1848–1938

-

![]()

Marcellus Simmons Woolley

1854–1921

-

![]()

Edwin Gordon Woolley Sr

1845–1930

-

![]()

Sarah Woolley Sutton

1847–1902

-

Joseph Wilding Woolley

1850–1877

-

![]()

Henry Alberto Woolley

1851–1894

-

![]()

Hyrum Smith Woolley

1852–1936

-

![]()

Orson Alpin Woolley

1853–1941

-

![]()

Edwin Thomas Woolley

1854–1924

-

![]()

Amelia Woolley Wardrop

1855–1936

-

![]()

Mary Ellen Woolley Smith

1855–1902

-

![]()

Ruth Woolley Hatch

1857–1934

-

![]()

Sarah Ann Woolley

1859–1859

-

![]()

Olive Woolley Kimball

1860–1906

-

![]()

William Edgar Woolley

1862–1862

-

![]()

Fannie Woolley Parkinson

1864–1946

-

![]()

George Edwin Woolley

1866–1938

-

![]()

Carlos Alfred Woolley

1868–1873

-

![]()

Clarence Herbert Woolley

1871–1877

Advertisement

Records on Ancestry

-

Geneanet Community Trees Index

-

Sons of the American Revolution Membership Applications, 1889-1970

-

Utah, U.S., Death and Military Death Certificates, 1904-1961

-

Membership of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 1830-1848

-

Salt Lake County, Utah, U.S., Death Records, 1908-1949

Sponsored by Ancestry

Advertisement