Here is a mention of her in Edwin Coppoc's biography

Description:

Edwin Coppoc (he dropped the "k" from his family name) was the 24-year-old Quaker martyr to the anti-slavery cause who followed John Brown to Harpers Ferry, Va. (W. Va.) and participated in the raid, was captured, tried for treason, condemned to die, and hanged on Dec. 16, 1859 at Charles Town, Va. (now W. Va.).

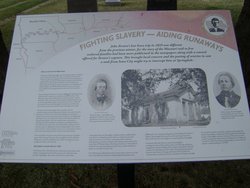

He was born of Quaker parents in the small village of Winona in 1835. His father died early in 1842, leaving a wife and six children ranging in age from one to ten years. Edwin was soon sent to live with John Butler, a Quaker abolitionist who lived on the Garfield Road. He stayed there for eight years, helping Butler transport slaves from one Underground Railroad station to another in the nearby towns of Salem, New Garden, Hanover and New Lisbon. The tactics used by slave-hunters made a deep impression on Coppoc.

At the age of 15, Edwin moved to Springdale, Iowa where his mother lived, married to a man named Raley. In the latter part of December 1857, John Brown and his party arrived in Springdale on their way from Kansas to Canada, in preparation for the attack on Harpers Ferry. Unable to raise enough money to proceed, Brown decided to remain in Springdale for the winter. Edwin and his brother Barclay, in sympathy with Brown's cause, enlisted under his leadership.

Brown left Iowa but the Coppoc brothers remained a while longer and then traveled to Winona, Ohio to visit old friends. It was not until late in August of 1859 that they arrived in Harpers Ferry.

The raid there took place on Oct. 16, 17 and 18, 1859. Edwin was captured on the morning of Oct. 18. He was held in the armory guard room until noon the following day and then taken to the jail in Charles Town, the county seat. Put on trial for treason, all five defendants received the same sentence – death by hanging; Brown on Dec. 2, and Coppoc and three others on Dec. 16. Abolitionists viewed them as martyrs.

Brown chose Harpers Ferry as his prime target because there was a federal arsenal there containing some 90,000 guns; arms that he desperately needed for his guerrilla army and for the slaves being liberated. Harpers Ferry is where the first mass-produced breech-loading rifles with interchangeable parts were manufactured.

Brown's little army consisted of 21 men (16 whites and five blacks). Eighteen of them went on the raid. As a form of disguise, Brown had changed his name to Isaac Smith and shortened his beard to about an inch. On the night of Oct 16, 1859, he led his party, armed with guns, pikes, a sledge hammer and crowbar, across the covered wooden railroad and wagon bridge into Harpers Ferry. They carried their rifles under gray woolen shawls.

Very quickly Brown seized the armory, arsenal and fire engine house. He and most of his men barricaded themselves in the engine house. Mayor Beckham, a kindly old man, was distressed at what was happening to his town and kept venturing out to see what was going on. Inside the engine house, Coppoc drew a bead on Beckham from the doorway and fired. He missed and fired again. Beckham, one of the best white friends blacks ever had, slumped to the ground. In his "Will Book" the mayor had provided upon his death for the liberation of Negro Isaac Gilbert, his slave wife and three children. Coppoc's shot had freed them all.

On Oct. 18 a detachment of U. S. Marines arrived, commanded by Colonel Robert E. Lee, and soon began battering down the oak doors of the engine house. Thirty-six hours after it had begun, Brown's raid for slave liberation ended in dismal failure. No uprisings took place. The raid cost a total of 17 lives. Two slaves, three townsmen, a slave-holder, and one Marine had been killed, and nine men wounded. Ten of Brown's raiders, including two of his sons, were killed or fatally injured. Five were captured and the rest escaped, including Barclay Coppoc.

At 11 a.m. on the day John Brown was to be executed (Dec. 2), he visited his fellow prisoners to bid them farewell. He talked with Coppoc, handed him a quarter and shook hands with him. Coppoc and another prisoner had a plan for escaping but it failed.

At 12:30 p.m. on Dec. 16, 1859, a wagon and two coffins stood at the door of the jail. Coppoc and John Cook were helped into the wagon to be seated atop their coffins. The procession slowly moved to the field of death. There was a large crowd in attendance. At 13 minutes before one, the wagon reached the scaffold and the two men ascended the scaffold.

After the rope had been adjusted about his neck, Coppoc exclaimed, "Be as quick as possible." These were his last words. A brief prayer was offered by a clergyman, the ropes adjusted, and both men were launched into eternity just seven minutes after they ascended the gallows.

After hanging for about 30 minutes the bodies were taken down and placed in poplar coffins. From Charles Town, Coppoc's remains were brought by Joshua Coppock (his uncle) and Thomas Winn to Joshua's home in Winona. Here the funeral took place on Sunday afternoon, Dec. 18, and was attended by nearly 2,000 people. Rachael Whinnery, a neighbor, read an address accusing the state of Virginia (a slave state) of murdering Coppoc, who was only acting in freedom's cause. The face of the corpse was much discolored and swollen, causing the appearance to be quite unnatural.

First interred in Winona, his body was moved to Salem on Dec. 30, 1859. In Winona there were guards armed with rifles watching over his grave because of rumors that pro-slavery sympathizers planned to steal the coffin. For several reasons it was thought best to remove Coppoc's remains to Salem. A document of explanation was signed by four leading citizens of Salem, with 24 other names appearing at the bottom. Coppoc's body was exhumed and brought to Salem on Dec. 30. Placed in a new metallic coffin, it lay in state at the town hall for several hours. At least 6,000 people viewed the body. Close relatives were at the front of the procession with the hearse, followed by pall bearers, blacks, citizens on foot, strangers and vehicles.

Coppoc's grave at Hope Cemetery is eight feet deep. The heavy metallic coffin was lowered into a box of two-inch planks on which a two-inch top piece was spiked and secured with irons. Six inches of clay were thrown onto the box, and five boulders, weighing from four to six-hundred pounds, were lowered into the grave. Dirt was thrown in, mixed with rye straw to prevent it from being shoveled out. All this was done to protect the grave from being robbed.

One of the most historic cemetery markers in the Salem area is the Edwin Coppoc stone at Hope Cemetery. The tall pointed shaft (an obelisk) of blackened sandstone was put in place on May 20, 1876 by Daniel Howell Hise and John Gordon. William Hichcliffe cut the stone and letters on the shield. This grave had been left unmarked for 16 years; from 1859 to 1876.

Many years later, William Hole raised funds for a bronze memorial tablet, and it was unveiled on May 30, 1935 in memory of Coppoc's 100th birthday. In 2003, the Coppoc grave marker and site was restored using funds donated by over a dozen Salemites. The stone was straightened, its base reinforced, and the bronze tablet restored. A special plaque now hangs in the Shaffer-Bradley Memorial Chapel listing the names of those who gave $100 or more.

Coppoc's original wooden coffin remained in Salem for many years. Then in 1921, Mrs. S. B. (Gertrude Whinnery) Richards turned it over to the Ohio State Archaeological and Historical Museum. She was the daughter of Dr. J. C. Whinnery, who recognized the historic value of the crude box, and preserved it in the attic of the building where the doctor's dental office was located (southwest corner of E. State St. and S. Broadway Ave.).

The coffin played a role in Salem's celebration when Lee surrendered. Citizens gathered downtown and soon formed a procession. Several young men knew where the coffin was being stored. They promptly secured possession of it, and bearing it upon their shoulders, formed the head of the procession. As they moved through the streets, they were followed by many others, and all joined in singing "Mine Eyes Have Seen the Glory of the Coming of the Lord," which was, indeed, the battle hymn of the republic.

In January of 1896, when Dr. S. L. Cope of Winona was passing through the museum of the state capitol in Indianapolis, he was attracted to war relics, among which was a gun with the following writing on it: "This musket was used by one of John Brown's men in the arsenal at Harpers Ferry in 1859. It was picked up by the Honorable D. W. Voohees, identified as the gun of Edwin Coppoc, and presented to Governor Willard, who deposited it in the library the following month." Edwin Coppoc was a cousin of Dr. Cope's wife.

Here is a mention of her in Edwin Coppoc's biography

Description:

Edwin Coppoc (he dropped the "k" from his family name) was the 24-year-old Quaker martyr to the anti-slavery cause who followed John Brown to Harpers Ferry, Va. (W. Va.) and participated in the raid, was captured, tried for treason, condemned to die, and hanged on Dec. 16, 1859 at Charles Town, Va. (now W. Va.).

He was born of Quaker parents in the small village of Winona in 1835. His father died early in 1842, leaving a wife and six children ranging in age from one to ten years. Edwin was soon sent to live with John Butler, a Quaker abolitionist who lived on the Garfield Road. He stayed there for eight years, helping Butler transport slaves from one Underground Railroad station to another in the nearby towns of Salem, New Garden, Hanover and New Lisbon. The tactics used by slave-hunters made a deep impression on Coppoc.

At the age of 15, Edwin moved to Springdale, Iowa where his mother lived, married to a man named Raley. In the latter part of December 1857, John Brown and his party arrived in Springdale on their way from Kansas to Canada, in preparation for the attack on Harpers Ferry. Unable to raise enough money to proceed, Brown decided to remain in Springdale for the winter. Edwin and his brother Barclay, in sympathy with Brown's cause, enlisted under his leadership.

Brown left Iowa but the Coppoc brothers remained a while longer and then traveled to Winona, Ohio to visit old friends. It was not until late in August of 1859 that they arrived in Harpers Ferry.

The raid there took place on Oct. 16, 17 and 18, 1859. Edwin was captured on the morning of Oct. 18. He was held in the armory guard room until noon the following day and then taken to the jail in Charles Town, the county seat. Put on trial for treason, all five defendants received the same sentence – death by hanging; Brown on Dec. 2, and Coppoc and three others on Dec. 16. Abolitionists viewed them as martyrs.

Brown chose Harpers Ferry as his prime target because there was a federal arsenal there containing some 90,000 guns; arms that he desperately needed for his guerrilla army and for the slaves being liberated. Harpers Ferry is where the first mass-produced breech-loading rifles with interchangeable parts were manufactured.

Brown's little army consisted of 21 men (16 whites and five blacks). Eighteen of them went on the raid. As a form of disguise, Brown had changed his name to Isaac Smith and shortened his beard to about an inch. On the night of Oct 16, 1859, he led his party, armed with guns, pikes, a sledge hammer and crowbar, across the covered wooden railroad and wagon bridge into Harpers Ferry. They carried their rifles under gray woolen shawls.

Very quickly Brown seized the armory, arsenal and fire engine house. He and most of his men barricaded themselves in the engine house. Mayor Beckham, a kindly old man, was distressed at what was happening to his town and kept venturing out to see what was going on. Inside the engine house, Coppoc drew a bead on Beckham from the doorway and fired. He missed and fired again. Beckham, one of the best white friends blacks ever had, slumped to the ground. In his "Will Book" the mayor had provided upon his death for the liberation of Negro Isaac Gilbert, his slave wife and three children. Coppoc's shot had freed them all.

On Oct. 18 a detachment of U. S. Marines arrived, commanded by Colonel Robert E. Lee, and soon began battering down the oak doors of the engine house. Thirty-six hours after it had begun, Brown's raid for slave liberation ended in dismal failure. No uprisings took place. The raid cost a total of 17 lives. Two slaves, three townsmen, a slave-holder, and one Marine had been killed, and nine men wounded. Ten of Brown's raiders, including two of his sons, were killed or fatally injured. Five were captured and the rest escaped, including Barclay Coppoc.

At 11 a.m. on the day John Brown was to be executed (Dec. 2), he visited his fellow prisoners to bid them farewell. He talked with Coppoc, handed him a quarter and shook hands with him. Coppoc and another prisoner had a plan for escaping but it failed.

At 12:30 p.m. on Dec. 16, 1859, a wagon and two coffins stood at the door of the jail. Coppoc and John Cook were helped into the wagon to be seated atop their coffins. The procession slowly moved to the field of death. There was a large crowd in attendance. At 13 minutes before one, the wagon reached the scaffold and the two men ascended the scaffold.

After the rope had been adjusted about his neck, Coppoc exclaimed, "Be as quick as possible." These were his last words. A brief prayer was offered by a clergyman, the ropes adjusted, and both men were launched into eternity just seven minutes after they ascended the gallows.

After hanging for about 30 minutes the bodies were taken down and placed in poplar coffins. From Charles Town, Coppoc's remains were brought by Joshua Coppock (his uncle) and Thomas Winn to Joshua's home in Winona. Here the funeral took place on Sunday afternoon, Dec. 18, and was attended by nearly 2,000 people. Rachael Whinnery, a neighbor, read an address accusing the state of Virginia (a slave state) of murdering Coppoc, who was only acting in freedom's cause. The face of the corpse was much discolored and swollen, causing the appearance to be quite unnatural.

First interred in Winona, his body was moved to Salem on Dec. 30, 1859. In Winona there were guards armed with rifles watching over his grave because of rumors that pro-slavery sympathizers planned to steal the coffin. For several reasons it was thought best to remove Coppoc's remains to Salem. A document of explanation was signed by four leading citizens of Salem, with 24 other names appearing at the bottom. Coppoc's body was exhumed and brought to Salem on Dec. 30. Placed in a new metallic coffin, it lay in state at the town hall for several hours. At least 6,000 people viewed the body. Close relatives were at the front of the procession with the hearse, followed by pall bearers, blacks, citizens on foot, strangers and vehicles.

Coppoc's grave at Hope Cemetery is eight feet deep. The heavy metallic coffin was lowered into a box of two-inch planks on which a two-inch top piece was spiked and secured with irons. Six inches of clay were thrown onto the box, and five boulders, weighing from four to six-hundred pounds, were lowered into the grave. Dirt was thrown in, mixed with rye straw to prevent it from being shoveled out. All this was done to protect the grave from being robbed.

One of the most historic cemetery markers in the Salem area is the Edwin Coppoc stone at Hope Cemetery. The tall pointed shaft (an obelisk) of blackened sandstone was put in place on May 20, 1876 by Daniel Howell Hise and John Gordon. William Hichcliffe cut the stone and letters on the shield. This grave had been left unmarked for 16 years; from 1859 to 1876.

Many years later, William Hole raised funds for a bronze memorial tablet, and it was unveiled on May 30, 1935 in memory of Coppoc's 100th birthday. In 2003, the Coppoc grave marker and site was restored using funds donated by over a dozen Salemites. The stone was straightened, its base reinforced, and the bronze tablet restored. A special plaque now hangs in the Shaffer-Bradley Memorial Chapel listing the names of those who gave $100 or more.

Coppoc's original wooden coffin remained in Salem for many years. Then in 1921, Mrs. S. B. (Gertrude Whinnery) Richards turned it over to the Ohio State Archaeological and Historical Museum. She was the daughter of Dr. J. C. Whinnery, who recognized the historic value of the crude box, and preserved it in the attic of the building where the doctor's dental office was located (southwest corner of E. State St. and S. Broadway Ave.).

The coffin played a role in Salem's celebration when Lee surrendered. Citizens gathered downtown and soon formed a procession. Several young men knew where the coffin was being stored. They promptly secured possession of it, and bearing it upon their shoulders, formed the head of the procession. As they moved through the streets, they were followed by many others, and all joined in singing "Mine Eyes Have Seen the Glory of the Coming of the Lord," which was, indeed, the battle hymn of the republic.

In January of 1896, when Dr. S. L. Cope of Winona was passing through the museum of the state capitol in Indianapolis, he was attracted to war relics, among which was a gun with the following writing on it: "This musket was used by one of John Brown's men in the arsenal at Harpers Ferry in 1859. It was picked up by the Honorable D. W. Voohees, identified as the gun of Edwin Coppoc, and presented to Governor Willard, who deposited it in the library the following month." Edwin Coppoc was a cousin of Dr. Cope's wife.

Family Members

Advertisement

See more Coppoc Raley or Lynch memorials in:

- Springdale Cemetery Coppoc Raley or Lynch

- Springdale Coppoc Raley or Lynch

- Cedar County Coppoc Raley or Lynch

- Iowa Coppoc Raley or Lynch

- USA Coppoc Raley or Lynch

- Find a Grave Coppoc Raley or Lynch

Explore more

Sponsored by Ancestry

Advertisement