Her husband, Charles A. Canfield, was a wealthy oilman who founded Chanslor-Canfield Midway Oil Co. in the 1880s. Later, he joined mining crony Edward L. Doheny and together they transformed the city by bringing in L.A.'s first gusher at the intersection of Patton and Colton streets on Crown Hill, just northwest of today's downtown, in 1892.

Canfield built a stately home not far away at 8th and Alvarado streets, where he lived with Chloe, their son and four daughters.

Chloe Canfield was a leader of the city's social and charitable activities. She was known for her great beauty, as well as for her generosity and kindness to the needy.

In January 1906, Chloe's husband and their daughter Daisy, and Daisy's oilman husband, J.M. Danziger, were away on business in Mexico--where Canfield and Doheny had made tens of millions from their oil discoveries.

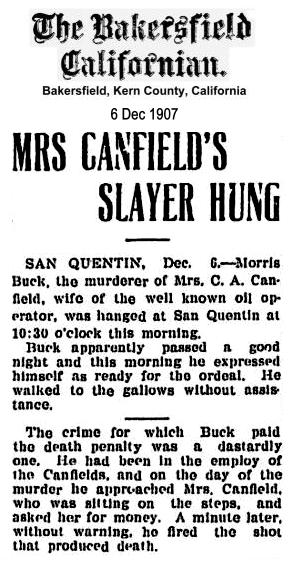

The family's wealth was very much on the mind of Morris Buck, 28, a former coachman for the Canfields, who knocked on the mansion's front door that day. Buck, who had been fired five years earlier for leaving the Canfields' horses unattended and beating them, had written Chloe to ask for a loan to start his own business. When no reply came, he arrived at the house to make his request in person.

The servants were terrified of Buck, who they believed was "a dope fiend and half crazy," and warned their employer not to see him.

Fearless, Chloe went to the door, accompanied by her small granddaughter, and invited Buck to sit down and talk on the front porch. When she refused to lend him $2,600, he stood and shot her.

Her granddaughter ran into the kitchen, screaming, "He's killing her!"

Wounded, the 46-year-old Chloe attempted to grab his gun, but he shot her again in the heart. As she fell onto the porch, he fired a third shot into her breast.

Fleeing the scene, Buck ran north on Alvarado Street before he was chased down by a bicycle cop and furious neighbors, who had watched the tragedy unfold.

The killer was captured a few blocks away, crouched behind the boathouse counter at Westlake--now MacArthur--Park.

Chloe's murder outraged thousands of Angelenos, who clamored for the lynching of her murderer.

When he returned from Mexico, the devastated Canfield told reporters that he would spend millions if necessary to ensure that Buck hanged. To that end, he persuaded the city's leading defense attorney, Rogers, to switch sides and become a "special prosecutor," assisted by his customary courtroom opponents, ex-Gov. Henry T. Gage and Dist. Atty. John D. Fredericks.

Relieved that they would not have to try the case against the defense bar's leading advocate, Gage and Fredericks both agreed that Rogers' extensive knowledge of medicine and psychology, with which he had saved so many accused killers from the gallows, would be invaluable.

"I'd feel safer with you on my side," Canfield kept telling Rogers.

Rogers, a professor of advocacy at USC's law school, also had a degree from the College of Osteopathic Physicians and Surgeons, as well as an extensive familiarity with cutting-edge scientific literature in several languages.

When it came time for the trial, a string of defense attorneys balked at being appointed to defend the accused. A.D. Warner finally drew the short straw and set out to prove that Buck was insane.

At one point, he dragged his client in front of the jury box and jerked Buck's head downward so the jurors could see for themselves the scars from multiple head injuries he had suffered over the years.

Not to be outdone, Rogers delivered a lecture on the "effects of every variety of head injury known to medical science" and urged jurors to feel Buck's head with their fingers so they could see for themselves that his scalp was perfectly healed.

When Buck fainted, Rogers called to the stand the superintendent of an insane asylum, who testified that, in his "expert opinion," the man never fainted.

Rogers prevailed, and Buck was sentenced to hang.

But victory afflicted the famous lawyer with a remorse that never healed. Only seconds after Buck was pronounced dead at San Quentin, Rogers wailed: "We're all wrong. . . . Who are we to take life? . . . I can't forgive myself."

Source: Tale of Wealth,

Murder and a Family's Decline

L.A. Then and Now August 20, 2000

Her husband, Charles A. Canfield, was a wealthy oilman who founded Chanslor-Canfield Midway Oil Co. in the 1880s. Later, he joined mining crony Edward L. Doheny and together they transformed the city by bringing in L.A.'s first gusher at the intersection of Patton and Colton streets on Crown Hill, just northwest of today's downtown, in 1892.

Canfield built a stately home not far away at 8th and Alvarado streets, where he lived with Chloe, their son and four daughters.

Chloe Canfield was a leader of the city's social and charitable activities. She was known for her great beauty, as well as for her generosity and kindness to the needy.

In January 1906, Chloe's husband and their daughter Daisy, and Daisy's oilman husband, J.M. Danziger, were away on business in Mexico--where Canfield and Doheny had made tens of millions from their oil discoveries.

The family's wealth was very much on the mind of Morris Buck, 28, a former coachman for the Canfields, who knocked on the mansion's front door that day. Buck, who had been fired five years earlier for leaving the Canfields' horses unattended and beating them, had written Chloe to ask for a loan to start his own business. When no reply came, he arrived at the house to make his request in person.

The servants were terrified of Buck, who they believed was "a dope fiend and half crazy," and warned their employer not to see him.

Fearless, Chloe went to the door, accompanied by her small granddaughter, and invited Buck to sit down and talk on the front porch. When she refused to lend him $2,600, he stood and shot her.

Her granddaughter ran into the kitchen, screaming, "He's killing her!"

Wounded, the 46-year-old Chloe attempted to grab his gun, but he shot her again in the heart. As she fell onto the porch, he fired a third shot into her breast.

Fleeing the scene, Buck ran north on Alvarado Street before he was chased down by a bicycle cop and furious neighbors, who had watched the tragedy unfold.

The killer was captured a few blocks away, crouched behind the boathouse counter at Westlake--now MacArthur--Park.

Chloe's murder outraged thousands of Angelenos, who clamored for the lynching of her murderer.

When he returned from Mexico, the devastated Canfield told reporters that he would spend millions if necessary to ensure that Buck hanged. To that end, he persuaded the city's leading defense attorney, Rogers, to switch sides and become a "special prosecutor," assisted by his customary courtroom opponents, ex-Gov. Henry T. Gage and Dist. Atty. John D. Fredericks.

Relieved that they would not have to try the case against the defense bar's leading advocate, Gage and Fredericks both agreed that Rogers' extensive knowledge of medicine and psychology, with which he had saved so many accused killers from the gallows, would be invaluable.

"I'd feel safer with you on my side," Canfield kept telling Rogers.

Rogers, a professor of advocacy at USC's law school, also had a degree from the College of Osteopathic Physicians and Surgeons, as well as an extensive familiarity with cutting-edge scientific literature in several languages.

When it came time for the trial, a string of defense attorneys balked at being appointed to defend the accused. A.D. Warner finally drew the short straw and set out to prove that Buck was insane.

At one point, he dragged his client in front of the jury box and jerked Buck's head downward so the jurors could see for themselves the scars from multiple head injuries he had suffered over the years.

Not to be outdone, Rogers delivered a lecture on the "effects of every variety of head injury known to medical science" and urged jurors to feel Buck's head with their fingers so they could see for themselves that his scalp was perfectly healed.

When Buck fainted, Rogers called to the stand the superintendent of an insane asylum, who testified that, in his "expert opinion," the man never fainted.

Rogers prevailed, and Buck was sentenced to hang.

But victory afflicted the famous lawyer with a remorse that never healed. Only seconds after Buck was pronounced dead at San Quentin, Rogers wailed: "We're all wrong. . . . Who are we to take life? . . . I can't forgive myself."

Source: Tale of Wealth,

Murder and a Family's Decline

L.A. Then and Now August 20, 2000

Sponsored by Ancestry

Advertisement

Records on Ancestry

Sponsored by Ancestry

Advertisement