~

Young, handsome and intellectual, full of enterprise, keen-sighted, suave in manner, faultless in dress, an associate of the first statesmen, soldiers and patriots of the land, and still holding himself to be only one of the plain people, is the briefly sketched character of John Kirby Allen, one of the founders of the city of Houston, and a man to whom the people of this city perhaps owe as much, and about whom they probably know as little, as they do of any man who ever figured in its history.

In view of Houston's present position as the railway center of Texas, with all the multifarious interests dependent thereon, it will be no exaggeration to say that John K. Allen showed a knowledge far beyond his day and generation, when, standing fifty-seven years ago on the banks of Buffalo Bayou, he pointed to the street along which the Houston & Texas Central Railroad now runs, and predicted that along that street in time would run one of the great trunk lines of Texas, and that Houston, by reason of its geographical position and many natural advantages, would one day be the railway metropolis of the great Southwest. Marvelous, prophetic words there were for a young man of twenty-seven to utter, but they were in keeping with his keen insight and his natural grasp of mind.

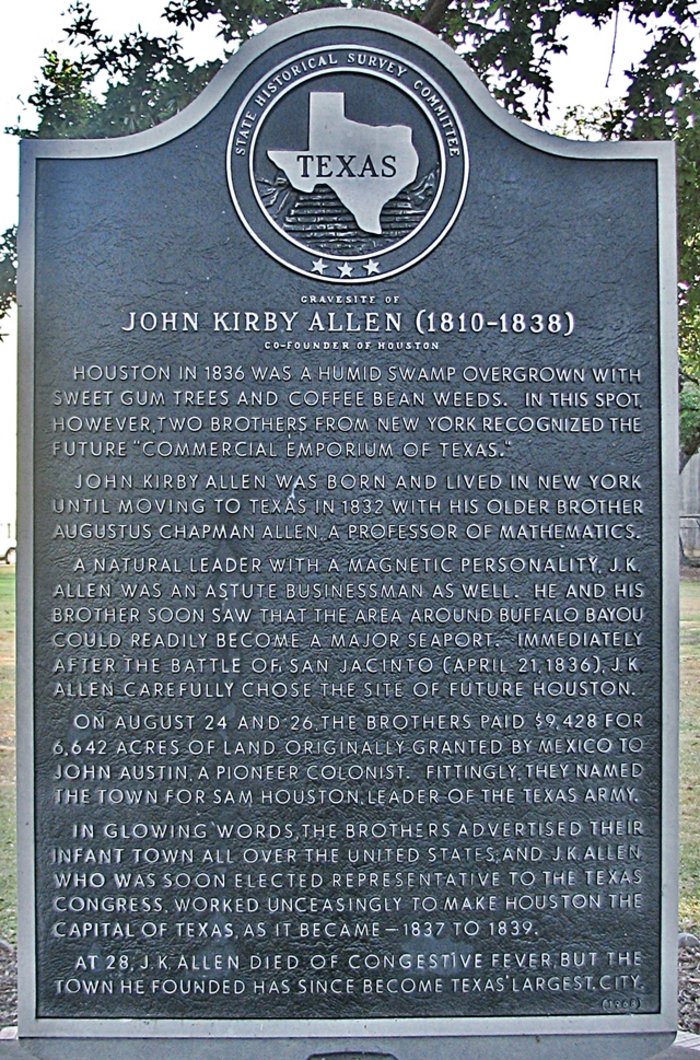

John Kirby Allen, third son of Roland and Sarah Allen (see memoir of Allen family elsewhere in this work), was born in Orrville, four miles from the present city of Syracuse, New York, in the year 1810. He was a precocious child, and a bright and interesting boy. Being one of the older members of a family of seven children, he did not enjoy the best educational advantages, but it is doubtful whether he would have taken a college course, as did two of his brothers, even if the opportunity had been offered. His was one of those natures that sought the quickening impulse to thought and the occasion for action by contact with men. He was born for action rather than reflection, and his naturally acute powers of intuition made up for all deficiency of book knowledge.

The bent of his mind was displayed even in childhood, and he began at a time when most children are the objects of parental care to show his cagerness to get out and do for himself. At the age of seven he obtained the consent of his parents to apply for a position as call boy in a hotel in Orrville, and in this capacity being the struggle for existence, a struggle, however, which was more a pleasure than a pain to him. His constant attention to his duties, his polite manners and courteous treatment of the guests were the subject of general remark, and soon won him favor, not only with his employer, but with all with whom he came in contact.

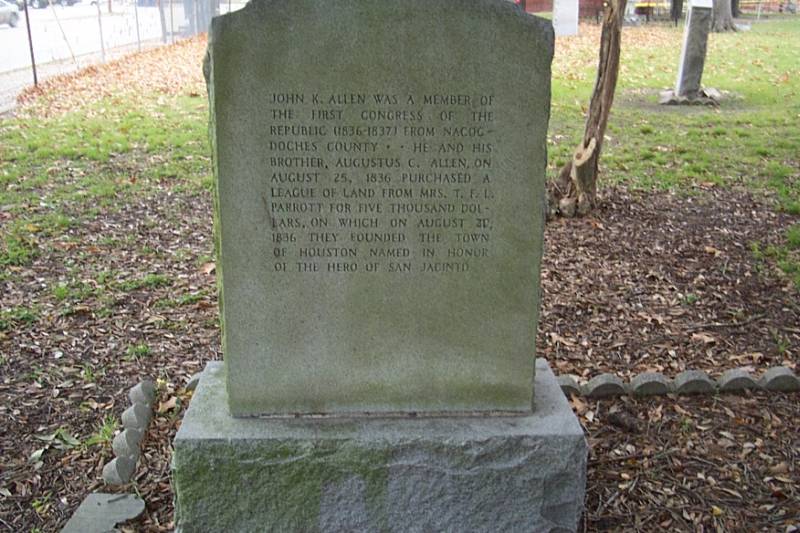

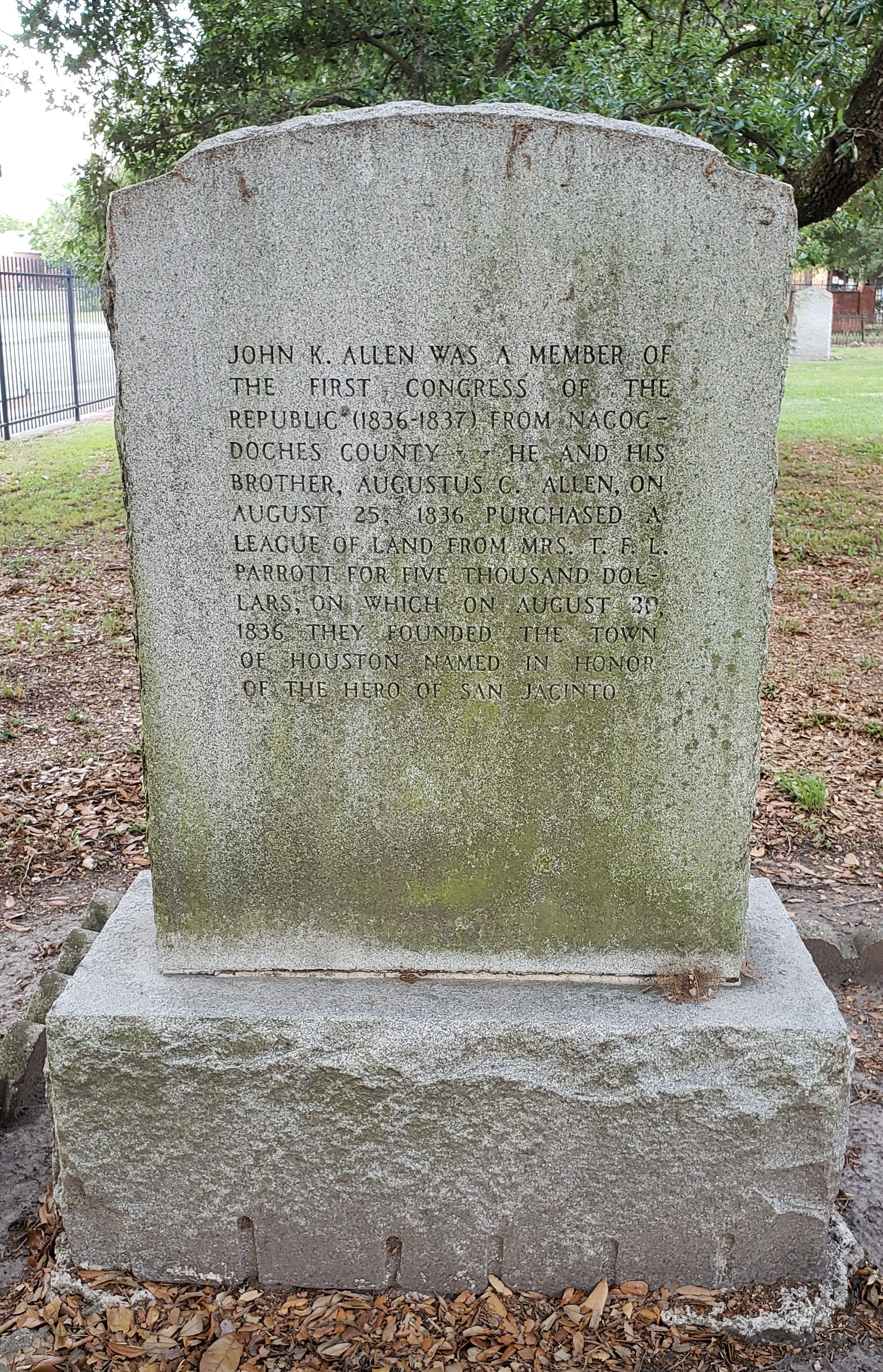

After quitting the hotel at Orrville he clerked for a while in a store, at the age of sixteen formed a partnership with a young man named Kittridge and began business for himself, opening a hat store in Chittenango, New York. The hat store was subsequently merged into a general dry-goods store and conducted successfully for two or three years, when he parted with his interests in it and went to New York city, where he joined his brother, Augustus C., then in the mercantile house of H. & H. Canfield, of that place. On the failure of this house in 1832 the Allen brothers came to Texas, and, locating at Nacogdoches, began that series of operations by which they subsequently became known throughout Texas, and in fact the entire Southwest. They bought, located and sold and traded land certificates, at which they made considerable money, being so engaged mostly in east Texas until after the battle of San Jacinto. Neither served in the field before that battle, although both were warm supporters of the cause of the colonists, were in active correspondence with many of the leading patriots, and Augustus C. soon after the battle entered the army, while John K. went as commissioner to New Orleans to solicit aid in behalf of the struggling settlers. Later John K. was a member of the Congress of the Republic, served also with the rank of Major on General Houston's staff, and in all things looking to a speedy termination of hostilities between Texas and Mexico, and the establishment of a permanent peace, he was one of the foremost both in counsel and in action.

During this time he was also busy with enterprises of a private nature, and in connection with his brother laid the foundation for what, but for his untimely death, would unquestionably have proved one of the most colossal fortunes in Texas. As time and chance have determined, the city of Houston was the most important of these enterprises, but it was only one of the many. The Allen brothers, at the time they projected the town of Houston, owned a controlling interest in the town site of Galveston, an interest in a town site to be made the county seat of Fort Bend county, and certificates to more than a hundred leagues of Texas land. They were stockholders in the Texas Railway, Navigation and Banking Company, chartered by the Congress of the Republic, December 16, 1836; and John K. was a partner in interest with J. Pinckney Henderson in a shipping business to be established between Texas and England. A mass of correspondence left by him and still preserved by one of his relatives, shows how many and varied were the enterprises in which he had an interest, and the measures which he had on foot in the early years of the Republic. The following document, taken from this source, will be of interest to the citizens of Houston of this date, and will give some idea of the practical views, and the clear-cut business methods of the subject of this sketch.

"To the members of the Senate the House of Representatives of the Congress of the Republic of Texas: As it is proposed to locate temporarily the seat of government of the Republic of Texas, I have the honor to propose for your consideration the town of Houston on Buffalo Bayou, conscientiously believing that it is decidedly the most eligible place for the seat of government, under the existing state of things.

"Texas is now in the midst of a revolution contending for national existence, and, although we have thus far successfully and gloriously maintained the contest, still we should recollect the fearful struggle in which we are engaged and remember that we have once been driven to the field of San Jacinto; that the Brazos country has once been in possession of the enemy and may be possibility be so again. We should remember that during the last campaign almost everything of a movable character was lost, and even the proceedings of the convention were saved with great difficulty. The great probability is that a new invasion of the country will take place, and if so it will be with a force that will require our whole united energies to resist; and although I have no doubt that we will manfully drive the invader back, still I at the same time consider that we should legislate as though danger and misfortune might come on us, and that we should, in locating the seat of government, have an eye to the comparative safety of the archives of the government. I consider that although the seat of government in times of peace ought to be on the west side of the Brazos, still that in so long as the revolution continues it ought to be to the east of it.

"I consider that the seat of government ought to be on the coast, because it combines the advantage of a safe and speedy communication with the United States and the interior of the country at the same time; because we will have more speedy and certain information of the operations of the enemy on the sea, and because the government will posses so many more facilities of communicating with the army and furnishing it with the necessary supplies.

"What place, I would inquire, possesses more advantages in this respect than the town of Houston? I boldly assert, None. It is one of the most healthy places in the lower country, as the experience of those who have lived for years in the neighborhood proves. It is a most beautiful site for a town, with most excellent spring water, and the most inexhaustible quantity of pine timber for building. The bayou is navigable at all times for boats drawing six feet of water, and is within ten hours' sail of Galveston Island, and there is no place in Texas that can be more easily supplies with everything desired from the United States. Fish, oysters and fowl can be had there in any abundance; and the country around is capable of supplying the town with all the substantial necessaries of life.

"This town is situated at the head of navigation-in the very heart of a rich country. It was selected as town which must become a great interior commercial emporium of Texas. The trade of upper Brazos, and Colorado, of Trinity and San Jacinto rivers, of Spring and Lake creek settlements, must find its way into Galveston bay through the town of Houston.

"Capitalists are interested in this town, and are determined to push it ahead by the investment of considerable capital, and at this moment contracts exist for the sending of 700,000 feet of lumber there; and I can assure the members that several stores of much capital will very soon be established there. A steamboat for the place has already been ordered out, and Colonel Benjamin F. Smith is now engaged in getting cut the lumber for a large house of public entertainment, and within four months from this time I can safely say that comfortable houses for all necessary purposes will there be erected.

"Should the Congress see proper to locate the seat of government at Houston I offer to give all the lots necessary for the purposes of the government. I also offer to build a State house and the necessary offices for the various departments of the government, and to rent them to the government on a credit until such time as it may be convenient to make payment. Or, if the government sees proper to erect the buildings, I propose when the seat of government is removed to purchase the said buildings at such price as they may be appraised at.

"In conclusion I assure the members that houses and comfortable accommodations will be furnished at Houston in a very short time, and if the seat of government is there located no pains will be spared to render the various officers of the government as comfortable as they could expect to be in any other place in Texas.

"John K. Allen, for A. C. & J. K. Allen."

It was the logic of this document that made Houston the temporary seat of government, which it became in May, 1837. With this temporary advantage and what he believed to be its many permanent advantages, Mr. Allen entered, heart and soul, as was his wont, into the task of building up the place, and making it a great interior commercial emporium of Texas. To demonstrate that the bayou was navigable for large vessels he and his brother chartered the Constitution, one of the largest steamers plying on the gulf, and ran it up to Houston, whence by the way originated the name Constitution Bend, this name being given to the wide place in the bayou some four miles south of the town, where the steamer was backed to before it could be turned around on its way out to Galveston. Liberal donations in the way of lots for schools, churches and public buildings were made, and the town soon entered on an era of great prosperity. Hither flocked numbers of settlers, speculators and adventurers, representatives of many nationalities and men of the most diversified tastes, interests and pursuits. As spokesman of the Houston Town Company and the one to whom all outside interests were entrusted, John K. Allen moved among this miscellaneous population with the ease and grace of a born leader and diplomat. A familiar picture of him, as some of the old settlers were accustomed in former years to draw it, was that of a man of youthful appearance, slight build, dressed with the most scrupulous care, of cordial but confident air, wending his way from place to place about the town, ever ready to dilate on the rising glories of the "great commercial emporium" and producing from the green bag which he always carried well filled with titles, papers, deed to lots, which he would present to any actual settler on condition that he make the necessary improvements. The faith of such a man in the future of the town inspired faith in others, and the interest he created was contagious. He was personally popular, and he made popular whatever measure he undertook to champion. He was on terms of intimate friendship with most of the distinguished men of those times, many letters being now found in his correspondence from such men as General Houston, Thomas J. Rusk, J. Pinckney Henderson, Samuel M. Williams, James Collingsworth and others.

Pity, one can not help but say, that a man with such gifts of mind and graces of person, such associations as he enjoyed, and such opportunities as he had by his own industry helped to make, was not permitted to live to finish the work so auspiciously begun. But it was not ordered by fate that he should, nor did any one ever fully realize the hopes by which he was inspired. In the closing days of the sultry month of July, 1838, he returned from the old cemetery, whither he had walked as one of the pall-bearers of his friend, Collingsworth, and complaining of a heavy head and a feeling of exhaustion, remarked that he would never make that trip to the cemetery again until he was taken there. Seized with a fever the same day, he died three days later, and was buried beside the lamented Collingsworth. He died at the early age of twenty-eight. His bones have long since mingled with the dust of mother earth, and, so far as the writer knows, his name cannot be found on the map of his adopted State or county, but that he was a man who if he had lived would have left the imprint of his genius upon the history of the country which he was proud to call his own, and that, too, in characters which would have been known and read of all men, there can be but little doubt. He was never married.

. (Source: History of Texas Biographical History of the cities of Houston & Galveston (1895)

~

Young, handsome and intellectual, full of enterprise, keen-sighted, suave in manner, faultless in dress, an associate of the first statesmen, soldiers and patriots of the land, and still holding himself to be only one of the plain people, is the briefly sketched character of John Kirby Allen, one of the founders of the city of Houston, and a man to whom the people of this city perhaps owe as much, and about whom they probably know as little, as they do of any man who ever figured in its history.

In view of Houston's present position as the railway center of Texas, with all the multifarious interests dependent thereon, it will be no exaggeration to say that John K. Allen showed a knowledge far beyond his day and generation, when, standing fifty-seven years ago on the banks of Buffalo Bayou, he pointed to the street along which the Houston & Texas Central Railroad now runs, and predicted that along that street in time would run one of the great trunk lines of Texas, and that Houston, by reason of its geographical position and many natural advantages, would one day be the railway metropolis of the great Southwest. Marvelous, prophetic words there were for a young man of twenty-seven to utter, but they were in keeping with his keen insight and his natural grasp of mind.

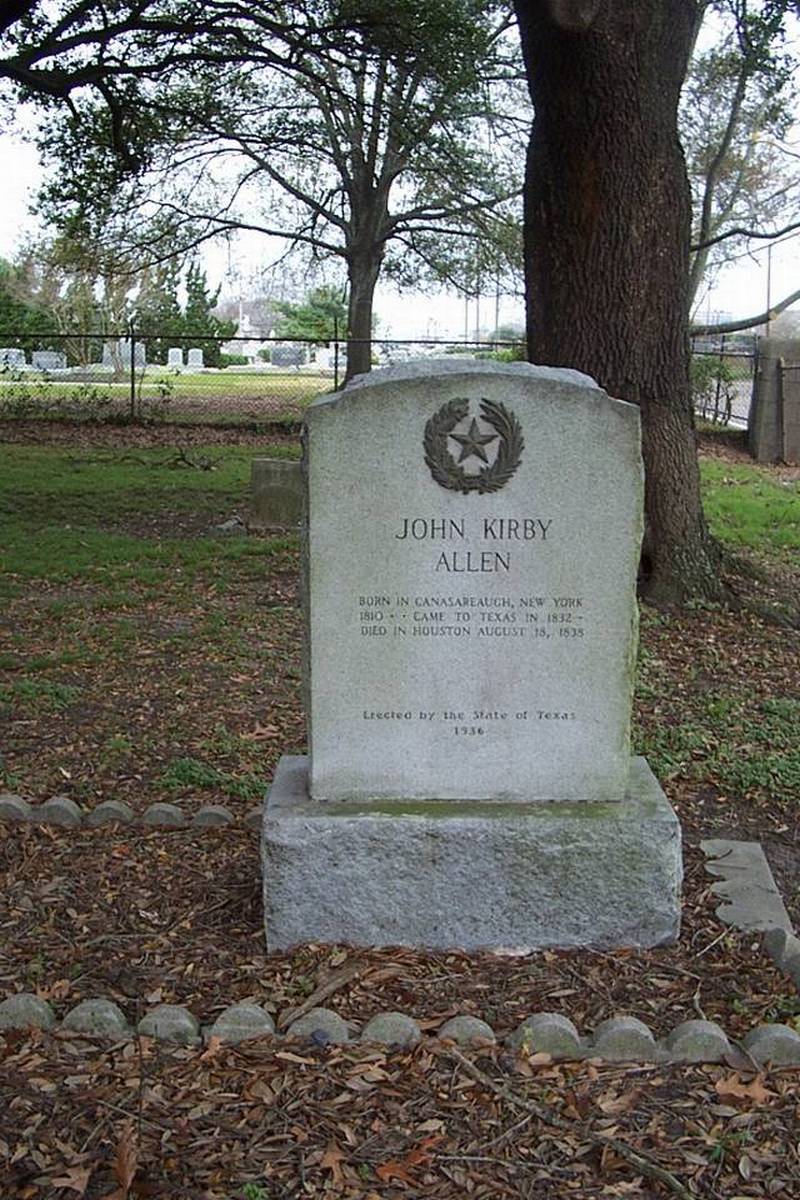

John Kirby Allen, third son of Roland and Sarah Allen (see memoir of Allen family elsewhere in this work), was born in Orrville, four miles from the present city of Syracuse, New York, in the year 1810. He was a precocious child, and a bright and interesting boy. Being one of the older members of a family of seven children, he did not enjoy the best educational advantages, but it is doubtful whether he would have taken a college course, as did two of his brothers, even if the opportunity had been offered. His was one of those natures that sought the quickening impulse to thought and the occasion for action by contact with men. He was born for action rather than reflection, and his naturally acute powers of intuition made up for all deficiency of book knowledge.

The bent of his mind was displayed even in childhood, and he began at a time when most children are the objects of parental care to show his cagerness to get out and do for himself. At the age of seven he obtained the consent of his parents to apply for a position as call boy in a hotel in Orrville, and in this capacity being the struggle for existence, a struggle, however, which was more a pleasure than a pain to him. His constant attention to his duties, his polite manners and courteous treatment of the guests were the subject of general remark, and soon won him favor, not only with his employer, but with all with whom he came in contact.

After quitting the hotel at Orrville he clerked for a while in a store, at the age of sixteen formed a partnership with a young man named Kittridge and began business for himself, opening a hat store in Chittenango, New York. The hat store was subsequently merged into a general dry-goods store and conducted successfully for two or three years, when he parted with his interests in it and went to New York city, where he joined his brother, Augustus C., then in the mercantile house of H. & H. Canfield, of that place. On the failure of this house in 1832 the Allen brothers came to Texas, and, locating at Nacogdoches, began that series of operations by which they subsequently became known throughout Texas, and in fact the entire Southwest. They bought, located and sold and traded land certificates, at which they made considerable money, being so engaged mostly in east Texas until after the battle of San Jacinto. Neither served in the field before that battle, although both were warm supporters of the cause of the colonists, were in active correspondence with many of the leading patriots, and Augustus C. soon after the battle entered the army, while John K. went as commissioner to New Orleans to solicit aid in behalf of the struggling settlers. Later John K. was a member of the Congress of the Republic, served also with the rank of Major on General Houston's staff, and in all things looking to a speedy termination of hostilities between Texas and Mexico, and the establishment of a permanent peace, he was one of the foremost both in counsel and in action.

During this time he was also busy with enterprises of a private nature, and in connection with his brother laid the foundation for what, but for his untimely death, would unquestionably have proved one of the most colossal fortunes in Texas. As time and chance have determined, the city of Houston was the most important of these enterprises, but it was only one of the many. The Allen brothers, at the time they projected the town of Houston, owned a controlling interest in the town site of Galveston, an interest in a town site to be made the county seat of Fort Bend county, and certificates to more than a hundred leagues of Texas land. They were stockholders in the Texas Railway, Navigation and Banking Company, chartered by the Congress of the Republic, December 16, 1836; and John K. was a partner in interest with J. Pinckney Henderson in a shipping business to be established between Texas and England. A mass of correspondence left by him and still preserved by one of his relatives, shows how many and varied were the enterprises in which he had an interest, and the measures which he had on foot in the early years of the Republic. The following document, taken from this source, will be of interest to the citizens of Houston of this date, and will give some idea of the practical views, and the clear-cut business methods of the subject of this sketch.

"To the members of the Senate the House of Representatives of the Congress of the Republic of Texas: As it is proposed to locate temporarily the seat of government of the Republic of Texas, I have the honor to propose for your consideration the town of Houston on Buffalo Bayou, conscientiously believing that it is decidedly the most eligible place for the seat of government, under the existing state of things.

"Texas is now in the midst of a revolution contending for national existence, and, although we have thus far successfully and gloriously maintained the contest, still we should recollect the fearful struggle in which we are engaged and remember that we have once been driven to the field of San Jacinto; that the Brazos country has once been in possession of the enemy and may be possibility be so again. We should remember that during the last campaign almost everything of a movable character was lost, and even the proceedings of the convention were saved with great difficulty. The great probability is that a new invasion of the country will take place, and if so it will be with a force that will require our whole united energies to resist; and although I have no doubt that we will manfully drive the invader back, still I at the same time consider that we should legislate as though danger and misfortune might come on us, and that we should, in locating the seat of government, have an eye to the comparative safety of the archives of the government. I consider that although the seat of government in times of peace ought to be on the west side of the Brazos, still that in so long as the revolution continues it ought to be to the east of it.

"I consider that the seat of government ought to be on the coast, because it combines the advantage of a safe and speedy communication with the United States and the interior of the country at the same time; because we will have more speedy and certain information of the operations of the enemy on the sea, and because the government will posses so many more facilities of communicating with the army and furnishing it with the necessary supplies.

"What place, I would inquire, possesses more advantages in this respect than the town of Houston? I boldly assert, None. It is one of the most healthy places in the lower country, as the experience of those who have lived for years in the neighborhood proves. It is a most beautiful site for a town, with most excellent spring water, and the most inexhaustible quantity of pine timber for building. The bayou is navigable at all times for boats drawing six feet of water, and is within ten hours' sail of Galveston Island, and there is no place in Texas that can be more easily supplies with everything desired from the United States. Fish, oysters and fowl can be had there in any abundance; and the country around is capable of supplying the town with all the substantial necessaries of life.

"This town is situated at the head of navigation-in the very heart of a rich country. It was selected as town which must become a great interior commercial emporium of Texas. The trade of upper Brazos, and Colorado, of Trinity and San Jacinto rivers, of Spring and Lake creek settlements, must find its way into Galveston bay through the town of Houston.

"Capitalists are interested in this town, and are determined to push it ahead by the investment of considerable capital, and at this moment contracts exist for the sending of 700,000 feet of lumber there; and I can assure the members that several stores of much capital will very soon be established there. A steamboat for the place has already been ordered out, and Colonel Benjamin F. Smith is now engaged in getting cut the lumber for a large house of public entertainment, and within four months from this time I can safely say that comfortable houses for all necessary purposes will there be erected.

"Should the Congress see proper to locate the seat of government at Houston I offer to give all the lots necessary for the purposes of the government. I also offer to build a State house and the necessary offices for the various departments of the government, and to rent them to the government on a credit until such time as it may be convenient to make payment. Or, if the government sees proper to erect the buildings, I propose when the seat of government is removed to purchase the said buildings at such price as they may be appraised at.

"In conclusion I assure the members that houses and comfortable accommodations will be furnished at Houston in a very short time, and if the seat of government is there located no pains will be spared to render the various officers of the government as comfortable as they could expect to be in any other place in Texas.

"John K. Allen, for A. C. & J. K. Allen."

It was the logic of this document that made Houston the temporary seat of government, which it became in May, 1837. With this temporary advantage and what he believed to be its many permanent advantages, Mr. Allen entered, heart and soul, as was his wont, into the task of building up the place, and making it a great interior commercial emporium of Texas. To demonstrate that the bayou was navigable for large vessels he and his brother chartered the Constitution, one of the largest steamers plying on the gulf, and ran it up to Houston, whence by the way originated the name Constitution Bend, this name being given to the wide place in the bayou some four miles south of the town, where the steamer was backed to before it could be turned around on its way out to Galveston. Liberal donations in the way of lots for schools, churches and public buildings were made, and the town soon entered on an era of great prosperity. Hither flocked numbers of settlers, speculators and adventurers, representatives of many nationalities and men of the most diversified tastes, interests and pursuits. As spokesman of the Houston Town Company and the one to whom all outside interests were entrusted, John K. Allen moved among this miscellaneous population with the ease and grace of a born leader and diplomat. A familiar picture of him, as some of the old settlers were accustomed in former years to draw it, was that of a man of youthful appearance, slight build, dressed with the most scrupulous care, of cordial but confident air, wending his way from place to place about the town, ever ready to dilate on the rising glories of the "great commercial emporium" and producing from the green bag which he always carried well filled with titles, papers, deed to lots, which he would present to any actual settler on condition that he make the necessary improvements. The faith of such a man in the future of the town inspired faith in others, and the interest he created was contagious. He was personally popular, and he made popular whatever measure he undertook to champion. He was on terms of intimate friendship with most of the distinguished men of those times, many letters being now found in his correspondence from such men as General Houston, Thomas J. Rusk, J. Pinckney Henderson, Samuel M. Williams, James Collingsworth and others.

Pity, one can not help but say, that a man with such gifts of mind and graces of person, such associations as he enjoyed, and such opportunities as he had by his own industry helped to make, was not permitted to live to finish the work so auspiciously begun. But it was not ordered by fate that he should, nor did any one ever fully realize the hopes by which he was inspired. In the closing days of the sultry month of July, 1838, he returned from the old cemetery, whither he had walked as one of the pall-bearers of his friend, Collingsworth, and complaining of a heavy head and a feeling of exhaustion, remarked that he would never make that trip to the cemetery again until he was taken there. Seized with a fever the same day, he died three days later, and was buried beside the lamented Collingsworth. He died at the early age of twenty-eight. His bones have long since mingled with the dust of mother earth, and, so far as the writer knows, his name cannot be found on the map of his adopted State or county, but that he was a man who if he had lived would have left the imprint of his genius upon the history of the country which he was proud to call his own, and that, too, in characters which would have been known and read of all men, there can be but little doubt. He was never married.

. (Source: History of Texas Biographical History of the cities of Houston & Galveston (1895)

Family Members

Advertisement

Explore more

Sponsored by Ancestry

Advertisement