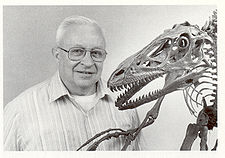

JOHN OSTROM did more than anyone else to make dinosaurs interesting, real and visceral — so much so that his discoveries were written into the book and film Jurassic Park.

From the mid-1960s he defied the popular belief that they were indolent, overgrown lizards which had blundered, deservedly, into an evolutionary tar pit. Many were, he said, quick-witted, agile, aggressive, warm-blooded, hawk-eyed and more akin to mammals than reptiles. More importantly, they were not a dead branch on the evolutionary tree but the direct predecessors of modern birds.

In the palaeontological community such ideas were greeted with outrage and ridicule. As Robert Bakker, one of Ostrom's first students at Yale, recalled in 1999: "They said, ‘Oh John, you're crazy'. The idea that dinosaurs were more firm of soul and quick of step was quite heretical." It took more than 30 years for Ostrom's beliefs to be vindicated.

Ostrom's bird theory was not new. In 1836 the Rev Edward Hitchcock concluded, after looking at dinosaur footprints, that they were "a race of ground eagles hunting in packs swiftly over the ancient New England landscape". T. H. Huxley, the 19th-century naturalist and defender of Darwin, put the dinosaur-avian link into a cogent theory. However, the idea became discredited, with scientists convinced that dinosaurs were entirely reptilian. "We were often told that dinosaurs were slow and stupid, and that people who studied them were slow and stupid," said Bakker.

John Harold Ostrom was born in New York in 1928 and grew up in Schenectady, New York State. After reading George Gaylord Simpson's Meaning of Evolution, he wrote to the author, who suggested that he enrol at Columbia University. He did so, and studied under Edward H. Colbert, then the acknowledged expert on dinosaurs.

Colbert followed the doctrine that dinosaurs were "sad, slow, stupid creatures that deserved to be extinct", and Ostrom did not begin to question it until after he graduated, with a doctorate in geology, in 1960. The next year he joined the geology faculty at Yale. He became a professor in 1971. He was also curator of vertebrate palaeontology at the Peabody Museum, Yale.

In 1963 he wrote a paper on hadrosaurs, which argued that these duck-billed dinosaurs were not like laggardly hippos, but upright and land-browsing — "like bipedal buffalos". The next year he found his palaeological golden fleece while fossil hunting in Montana: three claws sticking out of an eroded mound. He exposed a foot: three forward toes and an inner one that was a great, curved sickle. Ostrom named his find deinonychus, "Terrible Claw". The bones of this creature, in the words of Bakker, suggested an animal "the size of a wolf, but light and nimble — built at every joint for kickboxing". To function, such a creature required a high metabolic rate — and warm blood. It must have carried its tail erect, balancing the hunter as it sped forward.

Deinonychus, and the doors of debate it opened, polarised the palaeontological community, sparking furious disagreements which Ostrom, a modest and retiring scientist, was loath to get drawn into. Michael Crichton returned to the Terrible Claw discovery when writing the screenplay for Jurassic Park in 1993. The monster that appeared in film — the velociraptor — was, said Ostrom, "really our own deinonychus parading around under an assumed name".

Spielberg's film made his fictional predator perhaps four times the size of the beast that Ostrom had found. Yet in 1997 a giant raptor was discovered in Utah by friends of Bakker. The "Utahraptor" was a very close match to the tenacious killers in the movie, and was named Ostrommaysi, for Ostrom and Mays, the philanthropist who had funded the expedition.

Before it became a film star, however, deinonychus provided a firm foundation for the avian link.

A fossil, labelled a pterosaur, had been found in the same Bavarian quarries as several fossils labelled archaeopteryx. The pterosaur was duly relabelled the Haarlem archaeopteryx, and Ostrom was struck by how easy it was to confuse the pterosaur (a dinosaur) and the archaeopteryx (supposedly the first true bird), and how similar both were to his Terrible Claw.

He found more than 200 anatomical features shared by birds and predatory therapods: both species had a wishbone, swivelling wrists and three forward-pointing toes. The whole field underwent a renaissance, with many converting to Ostrom's view of evolution.

In 1996-97, long after Ostrom had given up teaching, the overwhelming belief that all dinosaurs were scaly was overturned. The sinosauropteryx, meaning "Chinese winged lizard", was discovered, and soon after this the National Geological Museum in Beijing revealed a collection of other new dinosaurs found, all clearly feathered therapods. One, protoarchaeopteryx, displayed symmetrical feathers that would serve no aerodynamic purpose, giving credence to the theory that feathers first evolved for warmth, then adapted to flight.

Many other discoveries since the mid-1960s — including indisputable evidence that dinosaurs nested and laid eggs — built up support for Ostrom's theory, which has now eclipsed all others.

Ostrom's wife, Nancy, died in 2002. He is survived by their two daughters.

John Ostrom, palaeontologist, was born on February 18, 1928. He died on July 16, 2005, aged 77."

JOHN OSTROM did more than anyone else to make dinosaurs interesting, real and visceral — so much so that his discoveries were written into the book and film Jurassic Park.

From the mid-1960s he defied the popular belief that they were indolent, overgrown lizards which had blundered, deservedly, into an evolutionary tar pit. Many were, he said, quick-witted, agile, aggressive, warm-blooded, hawk-eyed and more akin to mammals than reptiles. More importantly, they were not a dead branch on the evolutionary tree but the direct predecessors of modern birds.

In the palaeontological community such ideas were greeted with outrage and ridicule. As Robert Bakker, one of Ostrom's first students at Yale, recalled in 1999: "They said, ‘Oh John, you're crazy'. The idea that dinosaurs were more firm of soul and quick of step was quite heretical." It took more than 30 years for Ostrom's beliefs to be vindicated.

Ostrom's bird theory was not new. In 1836 the Rev Edward Hitchcock concluded, after looking at dinosaur footprints, that they were "a race of ground eagles hunting in packs swiftly over the ancient New England landscape". T. H. Huxley, the 19th-century naturalist and defender of Darwin, put the dinosaur-avian link into a cogent theory. However, the idea became discredited, with scientists convinced that dinosaurs were entirely reptilian. "We were often told that dinosaurs were slow and stupid, and that people who studied them were slow and stupid," said Bakker.

John Harold Ostrom was born in New York in 1928 and grew up in Schenectady, New York State. After reading George Gaylord Simpson's Meaning of Evolution, he wrote to the author, who suggested that he enrol at Columbia University. He did so, and studied under Edward H. Colbert, then the acknowledged expert on dinosaurs.

Colbert followed the doctrine that dinosaurs were "sad, slow, stupid creatures that deserved to be extinct", and Ostrom did not begin to question it until after he graduated, with a doctorate in geology, in 1960. The next year he joined the geology faculty at Yale. He became a professor in 1971. He was also curator of vertebrate palaeontology at the Peabody Museum, Yale.

In 1963 he wrote a paper on hadrosaurs, which argued that these duck-billed dinosaurs were not like laggardly hippos, but upright and land-browsing — "like bipedal buffalos". The next year he found his palaeological golden fleece while fossil hunting in Montana: three claws sticking out of an eroded mound. He exposed a foot: three forward toes and an inner one that was a great, curved sickle. Ostrom named his find deinonychus, "Terrible Claw". The bones of this creature, in the words of Bakker, suggested an animal "the size of a wolf, but light and nimble — built at every joint for kickboxing". To function, such a creature required a high metabolic rate — and warm blood. It must have carried its tail erect, balancing the hunter as it sped forward.

Deinonychus, and the doors of debate it opened, polarised the palaeontological community, sparking furious disagreements which Ostrom, a modest and retiring scientist, was loath to get drawn into. Michael Crichton returned to the Terrible Claw discovery when writing the screenplay for Jurassic Park in 1993. The monster that appeared in film — the velociraptor — was, said Ostrom, "really our own deinonychus parading around under an assumed name".

Spielberg's film made his fictional predator perhaps four times the size of the beast that Ostrom had found. Yet in 1997 a giant raptor was discovered in Utah by friends of Bakker. The "Utahraptor" was a very close match to the tenacious killers in the movie, and was named Ostrommaysi, for Ostrom and Mays, the philanthropist who had funded the expedition.

Before it became a film star, however, deinonychus provided a firm foundation for the avian link.

A fossil, labelled a pterosaur, had been found in the same Bavarian quarries as several fossils labelled archaeopteryx. The pterosaur was duly relabelled the Haarlem archaeopteryx, and Ostrom was struck by how easy it was to confuse the pterosaur (a dinosaur) and the archaeopteryx (supposedly the first true bird), and how similar both were to his Terrible Claw.

He found more than 200 anatomical features shared by birds and predatory therapods: both species had a wishbone, swivelling wrists and three forward-pointing toes. The whole field underwent a renaissance, with many converting to Ostrom's view of evolution.

In 1996-97, long after Ostrom had given up teaching, the overwhelming belief that all dinosaurs were scaly was overturned. The sinosauropteryx, meaning "Chinese winged lizard", was discovered, and soon after this the National Geological Museum in Beijing revealed a collection of other new dinosaurs found, all clearly feathered therapods. One, protoarchaeopteryx, displayed symmetrical feathers that would serve no aerodynamic purpose, giving credence to the theory that feathers first evolved for warmth, then adapted to flight.

Many other discoveries since the mid-1960s — including indisputable evidence that dinosaurs nested and laid eggs — built up support for Ostrom's theory, which has now eclipsed all others.

Ostrom's wife, Nancy, died in 2002. He is survived by their two daughters.

John Ostrom, palaeontologist, was born on February 18, 1928. He died on July 16, 2005, aged 77."

Family Members

Sponsored by Ancestry

Advertisement

Advertisement