----

Hoodlums did society a favour by blasting each other to death.

The kingpin of the Melbourne underworld for years after the end of World War 1 was a bowler-hatted, diminutive figure named Joseph Theodore Leslie "Squizzy" Taylor.

One evening in 1927, he went gunning for "Snowy" Cutmore, a rival gangland boss, who was reportedly lying ill in bed with flu, barely able to lift his head. Revolver in hand, he invaded Cutmore's sick room, unaware that his suspected victim had prepared himself for trouble with a gun under the pillow.

In the gun duel that erupted in the bedroom of a squalid Carlton slum house, Cutmore put a shot near Taylor's heart before falling back dead with a bullet in his brain. Taylor staggered out but died shortly after in Melbourne's St Vincent's Hospital – and two of Australia's most vicious criminals had cancelled each other out.

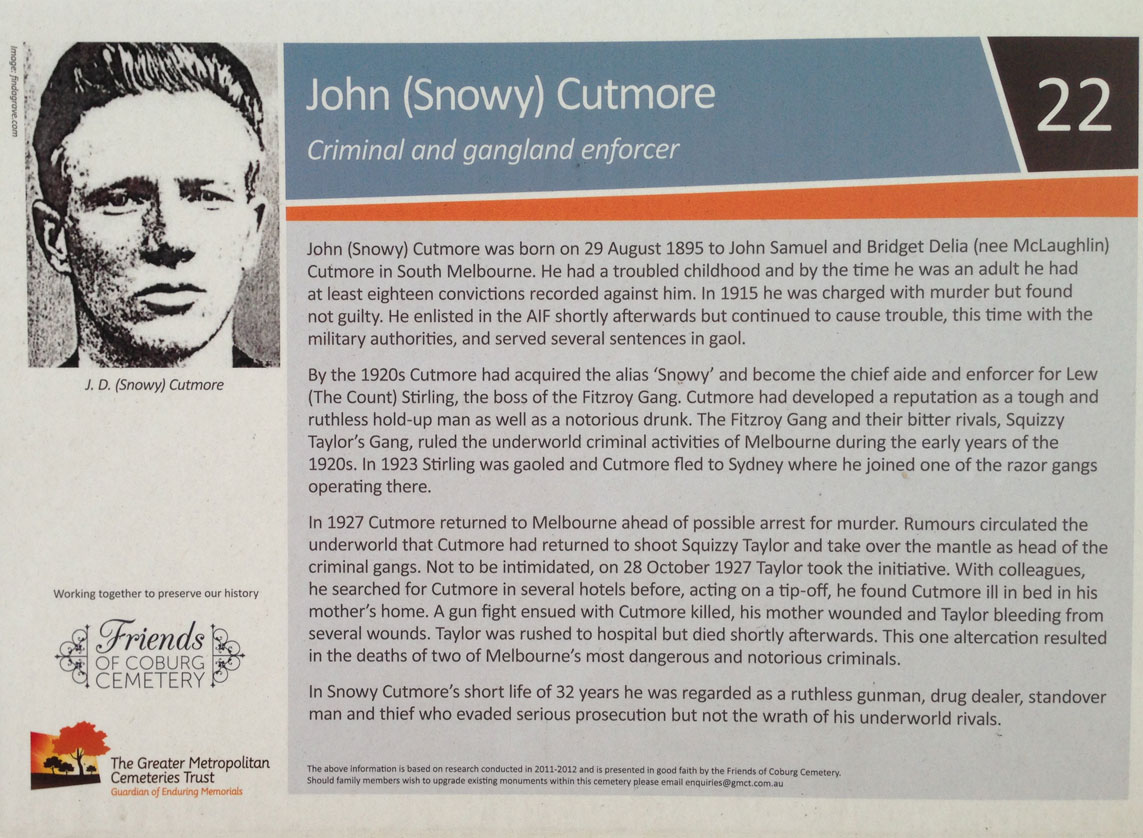

Back when the roaring twenties dawned, a former New York criminal, Lew "The Count" Stirling had arrived on the scene and ruled Melbourne's Fitzroy gang. As his chief aide and enforcer, The Count had enlisted John Daniel "Snowy" Cutmore, a 90kg local bruiser and hold-up man, who was ruthless, tough and violent. He was notorious in Fitzroy as a crazy brawler in brothels and drinking dens. In his half-drunken rages, he was like a wild animal, once branding a reluctant prostitute with a hot iron.

There was bitter open warfare between the Fitzroy gang and Squizzy Taylor's gang for years. Hit-and-run shooting affrays flared and there were constant brawlings and knifings.

By 1923, The Count was in prison and Snowy Cutmore had fled to Sydney to join up with one of the infamous razor gangs operating there. In 1927, Snowy Cutmore arrived back in Melbourne. Word flashed through the underworld that he had come to shoot Squizzy Taylor and take over the Melbourne rackets. In fact, Snowy had quit Sydney because police had him marked down as a prime suspect for the murder of another Melbourne hoodlum, Norman Bruhn, in a Darlinghurst lane.

Squizzy decided to get in first and shoot Cutmore. But instead of deputing someone else to do the job, he went gunning for his old enemy himself, so sure of his power that he believed he could get away with murder, even before witnesses.

Late on the afternoon of October 27, armed with a revolver and accompanied by two of his followers, Taylor went looking for Cutmore in several Melbourne hotels he frequented. Someone whispered to him that Cutmore was in bed at his mother's house, hardly able to lift his head because of influenza. Taylor took a taxi to one of a terrace of four slum dwellings in Barkly St, Carlton, where Snowy's mother lived. Cutmores sister answered the door. Squizzy brushed past her and walked down a passage to a room at the rear where Cutmore lay on a double bed in the gloom, waiting for his mother to poultice his chest. Gun in hand, Taylor burst into the room and began shooting at what he thought was an unarmed man. But Cutmore whipped a revolver from beneath his pillow and returned the fire. Snowy's mother rushed in and fell with a bullet from her son's own gun. The battle continued until both revolvers were empty.

Leaving Cutmore dead from five bullets, Taylor, with blood pouring from his wounds, managed to get back to the street and fall into the taxi. His companions ordered the driver to rush him to hospital. Squizzy died soon after arrival and so one vicious gun duel had rid Melbourne of two of the most dangerous criminals in Australia.

From: "Daily Mirror" (Sydney) Wednesday February 28th 1990

-----

John Daniel Cutmore had had 18 convictions recorded against him since 1914. Known as "Snowy" Cutmore, he had also appeared under various aliases, including that of John McLaughlin, John Nolan, John Watson, and John Harris. His longest sentence was 12 months in Sydney in 1923 for thieving. His offences included assaulting the police, shooting with intent to do grevious bodily harm, and thieving. While in gaol in Victoria he gave little trouble to the authorities, but was a source of considerable worry to the detectives, who, while suspicious, were very often unable to obtain convictions. He was said to have usually carried a revolver, and was suspected of more than one "hold-up." In police circles he was regarded as a dangerous criminal, whose cleverness enabled him to escape the consequences of many crimes.

In 1915 Cutmore was suspected of having been associated with the murder of a sailor in Melbourne. He was presented for trial, and was found not guilty. He joined the Australian Imperial Forces, but did not leave Victoria. He gave a great deal of trouble to the military authorities, and served sentences on various occasions in Geelong and other gaols, and also in Langwarrin.

- Melbourne Argus, October 28, 1927

-----

As a sequel to what is believed to have been a private feud of long standing, two men were shot dead, and a woman was seriously injured in a house in Carlton early last night. They were:-

Dead

- Taylor, Joseph Theodore Leslie (known as "Squizzy"), aged 43 years, of Darlington street, Richmond.

- Cutmore, John, aged 38 years, of Barkly street, Carlton.

Wounded

- Cutmore, Bridget Delia, aged 58 years, of Barkly street, Carlton, mother of John Cutmore.—Suffering from a bullet wound in the right shoulder. Admitted to the Melbourne Hospital.

Hailing a taxi-cab in Lonsdale Street at 5 o'clock yesterday evening, Taylor, accompanied by two men, ordered the driver, John William Hall, to go to Carlton. When he engaged the cab Taylor gave no indication of his destination beyond saying that he wished to visit an hotel in Carlton. Calls were made to several hotels in the vicinity of Rathdown, Lygon, and Elgin streets. The movements of the men indicated that they were in search of another person or persons. Their conversation, however, gave no clue as to whom they were seeking. Eventually Taylor told the driver to go to Barkly Street. Turning from Rathdown Street the cab had only travelled a few yards in a northerly direction along Barkly street, when the driver was told to stop. Taylor, accompanied by one of his friends left the cab, and walking some distance along the northern side of the street went into one of a terrace of houses. The third man, as far as is known, remained in the car.

When they reached the house the front door was open. The occupants were accustomed to strangers entering—some of the rooms are occupied by lodgers—and no attention was attracted as Taylor and his companion walked through the house to a small room at the rear, where Cutmore was lying in bed, suffering from an attack of influenza. According to statements made to the police, only a few words were spoken but these were indistinguishable. Suddenly the attention of Mrs. Bridget Cutmore, the mother of the dead man, was attracted by the report of a revolver shot. Other shots followed in quick succession. Hurrying to the room, Mrs. Cutmore saw two men, one of whom was holding a revolver. Her son had not left his bed. While she stood in the doorway she received a shot in the right shoulder. Although in a dazed condition she recollects that one man left the house by the front door, while the second man ran into the back yard, presumably leaving by a gate leading to a lane.

Taylor staggered towards the car, which was waiting in the street, and exclaimed, "I am shot. Take me to hospital." His companion helped him into the car, and told the driver to hurry to St. Vincent's Hospital. Travelling by way of Johnston Street the car was delayed for some minutes in a traffic crush at the intersection of Brunswick street. Apparently disregarding the serious condition of his friend, Taylor's companion opened the door of the motorcar—a sedan—and jumping out, said to the driver, "You had better see this through yourself." He disappeared down Brunswick street. Realising that no time should be lost in getting his passenger to the hospital, Hall hurried to St. Vincent's Hospital. Taylor was assisted into the casualty ward, where he was found to be unconscious. His death occurred 20 minutes later. An examination showed that Taylor had received a bullet wound on the right side below the ribs.

Occurring at a time when it was thought that any feuds which had existed among members of the criminal class had been buried, the shooting created a sensation at police headquarters, and revived memories of the Fitzroy vendetta. The police have no definite knowledge of the cause of the rivalry between Taylor and Cutmore. It is said, however, that jealousy concerning a woman was the main reason of their enmity. Cutmore, who was well known to the police, left Melbourne some months ago, and with his wife took up residence in Sydney. He returned to Melbourne last Sunday with his wife and went to live with his mother in Barkly Street, Carlton. It is known that he visited the Richmond racecourse in company with a man who is said to have occupied a room as a lodger in the house in Barkly Street. Since then, however, he had been confined to bed with a severe attack of influenza. It is assumed that Taylor, hearing of his return from Sydney, set out yesterday evening with the object of finding him.

The house in which the Cutmores lived is one of a terrace of four old-fashioned brick cottages on the northern side of Barkly street, about 50 yards from the corner of Rathdown street. The dwelling is single-fronted, abutting on to the footpath. The main rooms of the house are reached from a narrow passage leading from the front door to a doorway giving access to the back yard. The room occupied by Cutmore yesterday is at the extreme rear of the house, and was neatly furnished. It had one window, facing the back yard. A peculiar feature of the shooting is that, although there are houses adjoining the Cutmore's home on either side, the attention of no one in the vicinity was attracted by the shots.

When news of the affair became public, mainly through the arrival of the police and ambulances, much excitement and speculation about the cause of the deaths of the two men was evident, and for many hours the Cutmore's home was the object of the curiosity of a large crowd.

Although her condition is considered serious Mrs. Cutmore was well enough last night to be interviewed by Detective-sergeants Davey and Brophy in No. 6 ward at the Melbourne Hospital. In her statement she was unable to say much of the tragedy which involved the death of her son.

"I was in the kitchen preparing the evening meal," said Mrs Cutmore, "when I heard footsteps in the passage. I took no notice, as some of the rooms in the house are let to lodgers, and I thought perhaps it was one of them returning home. It also occurred to me that it might have been one of the many friends who had called to see my son since he returned from Sydney. The front door had been left open by my son's wife, who had left the house to buy some milk at a shop near by. Shortly after I heard the footsteps in the passage I heard men's voices in my son's bedroom. The words were not distinct, but I did not think that there was a quarrel. Suddenly I heard two shots. While hurrrying into my son's room I heard several more shots, and on opening the door I saw two men standing at the end of his bed, which faced towards the back yard. Before I could even see my son another shot was fired and I felt a sharp pain in my right shoulder. I was dazed for the moment, and so unexpected was the whole affair that I cannot say which of the two men was carrying a gun, nor did I see that one of the men was seriously wounded. They both brushed past me into the passage, and one ran out of the back door, while the other seemed to stagger up the passage towards the front door. In the bedroom I saw my son lying on the bed. It seemed only a few minutes before the police arrived and I was taken to the hospital."

A pathetic incident occurred at the end of the interview of Mrs. Cutmore by the detectives at the hospital last night, when she was told of her son's death. Apparently she knew that he had been wounded, and asked Detective-sergeant Brophy if he was seriously ill. When told that he had been shot dead Mrs. Cutmore was obviously affected.

An X-ray examination of Mrs. Cutmore is to be made this morning, and it is expected that an operation for the removal of the bullet will be carried out during the day.

From descriptions given to the police, it is apparent that Taylor's companion, who left the house by the back door, is identical with a man who hurried to the surgery of Dr. McCutcheon, in Rathdown Street, and told him of the shooting, and later went to the Carlton police station for assistance. He then disappeared, and up till a late hour last night had not been traced by the detectives. Search was also made in the city and suburbs for the second man, who jumped out of the taxi-cab at the corner of Brunswick and Johnston streets, Fitzroy. In their efforts to find these men from the meagre descriptions which had been supplied, a large party of detectives visited the hotels in the Carlton district at which the taxi-cab had called during the afternoon. They were, however, unable to trace either of Taylor's companions.

An extraordinary feature of the tragedy which is engaging the close attention of the detectives is the fact that one of the revolvers used in the duel has disappeared. A .32 automatic six-chambered pistol, which was empty, was found in Taylor's possession when a Fitzroy constable searched his clothes at St. Vincent's Hospital. Reconstructing the duel last night, Sub-inspector Piggott advanced the theory that, of the succession of shots in the bedroom, Taylor fired six, as the chambers of his pistol were empty. That the shots were fired by each man simultaneously is indicated from an examination made last night by the police of Taylor's weapon. Evidently a bullet from Cutmore's revolver struck the barrel of Taylor's pistol, and, glancing off, inflicted a flesh wound in the little finger of his right hand. Part of the nickel cap of a bullet, apparently from Cutmore's revolver, had become jammed in one of the chambers.

From his youth the life of Leslie Taylor was a sordid record of criminality. Taylor, who affected smartness of dress and "polish" in his dealings with the police force, delighted to surround himself with an air of mystery and cleverness. By his spectacular exploits he came to be regarded as a master-mind among criminals. This reputation was not well-founded. Taylor was a criminal of ordinary mentality, whose distinguishing features were his callous disregard for the lives of others, his treachery towards his associates, and his personal cowardice.

Leslie Taylor, alias Leslie Grout, alias Michael McGee, was born at Brighton in 1884, and was one of the family of five brothers and two sisters. After receiving a state school education he worked for three years in a training stables, and from then on, so far as is known, he did no honest work. His early criminal record included imprisonment for 21 days for larceny in 1896, and imprisonment on no less than five occasions in 1907 on minor charges. Subsequent offences for which he received sentences included larceny, assault, vagrancy, stealing from the person, and obstructing the police. His total convictions until 1916 numbered 18.

The robbery and murder of a commercial traveller, Mr. Arthur Trotter, at his home at Fitzroy, on January 7, 1913, for which Harold Thompson, a labourer, was tried, was committed by three men, one of whom the police believe was Taylor, although no direct evidence could be obtained. Thompson was arrested after a reward had been offered and the chief evidence against him consisted of finger prints. It was considered that this evidence was insufficient, and the prisoner was acquitted.

Late on the night of February 28, 1916, the garage manager of the Globe Motor and Taxi Company was called by telephone by a man who said that his name was Lestrange, and ordered a car for the following day to take him to Eltham. He asked for the number of the car, and particularly requested that it should not be of a certain make. The order was booked, and on the following day William Haines, who was a relieving driver only, was sent to the address given. He left the garage at five minutes to 8 o'clock in the morning, and nothing more was heard of him until late on the same night his body was found huddled on the floor of his car at the junction of Bulleen and Templestowe roads, at Heidelberg. The body had been covered by a motor rug and hidden from view. Bullet wounds in the head and neck showed that Haines had been a victim of a cold-blooded and diabolical crime, for which the entire absence of apparent motive baffled the detectives engaged on the case. The car had been noticed by people at the side of the road several hours before the body of Haines was discovered. A fortnight after the discovery of the body, Taylor and another man were charged with the murder. When charged, Taylor broke into tears and explained that he did not murder anybody. Earlier in the day both men had been brought before the City Court and sentenced to imprisonment for 12 months on charges of vagrancy. Their trial for murder began on April 18, when the Crown case was that the accused had intended to rob a bank manager who was taking bank money from Doncaster to Templestowe. It was the belief of the police that Taylor and his accomplice, intending to make Haines drive them to a suitable spot where they could disguise themselves, and that they evidently expected that the promise of a substantial share in the booty would have induced Haines to assist in the crime. It was found that a grave had been prepared at Clayton, several miles away, and the theory was that the body of the bank manager was to be placed in this grave. Among the witnesses for the prosecution was the matron at the City Watchhouse, who repeated conversation concerning identification between the prisoners which she had overheard. During this conversation Taylor had said, "They can't very well pot us. They can't identify us." In his summing up, Mr. Justice Hood told the jury that the evidence of identification showed simply that one of the murderers was tall, and the other short, and he added that if the jury believed the story for the defence it was extremely strong. Taylor and the other man were found not guilty.

Taylor appealed against his sentence of 12 months for vagrancy, but on the evidence of several detectives that he was a known associate of criminals and undesirable characters, the appeal was dismissed. A second appeal by Taylor against the sentence for obstructing the police in the execution of their duty was also dismissed.

The "Fitzroy Vendetta," as it was known, which lasted for many months in 1919, formed one of the most extraordinary chapters of Taylor's sordid career. The vendetta arose, it is believed, from a quarrel among a number of criminals over the disposal of jewellery obtained in a carefully planned robbery of a Collins street jeweler's shop. Some months after the robbery a woman associated with one of the criminals appeared at an "underworld" party wearing a quantity of jewellery which other guests recognised as a portion of the haul to which they considered that they were entitled. For months afterwards there was a bitter war between opposing parties of criminals, one of which Taylor was supposed to lead. The victims in these affrays never sought the assistance of the police and when they were so seriously injured that the police were able to interview them, they maintained an obstinate silence regarding the identity of their assailant. One man was brought to hospital in the early hours of the morning with six bullet wounds in his head. He recovered. Other shootings occurred, but no one was killed, and eventually the feud died.

In 1921 Taylor absconded from bail of £300, which had been fixed in connection with a charge against him of having broken and entered a warehouse and bond store in King street. For more than 12 months the police searched for him unsuccessfully. During the 14 months that he was in hiding many messages had come from him to the police promising to give himself up when he was ready. The eventual surrender was carefully arranged between Taylor's friends and the detectives. Punctually at a quarter past 8 o'clock on the morning of Thursday 22, 1922—the night arranged with the police—a large motor-car stopped outside the detective office. Taylor stepped out, paid the chauffeur. He told the detectives that he had never had any intention of running away. He added that he had spent most of his time in a flat in East Melbourne, and he told the police that he had often come out of hiding in disguise and had attended several race meetings sometimes dressed as a woman, but more often as a schoolboy in knickers. Taylor was a "showy" criminal, who thought a great deal of impressing members of the underworld, and the detectives were sceptical about the truth of the story. He was again committed for trial on the charge of having entered the warehouse, and was once more released on bail. His trial took place early in October. On the day before it took place a man who was walking up Bourke street about 8 o'clock in the evening fired three shots at Taylor as he alighted from a motor-car near the entrance to the Bookmakers' Clerks' Association. Alarmed pedestrians ran in all directions. Taylor was shot in the right leg, and fearing that further shots would be fired limped across the footpath and was assisted into the motor-car. Taylor's assailant escaped as soon as the shot had been fired, but later a man was arrested on a charge of having shot at Taylor. Taylor limped into the dock on crutches to answer the charge of entering the warehouse and in answer to the charge he said that he had been drinking heavily, and that an enemy of his had challenged him to fight. Running away he had entered the warehouse, and when he heard the police whistle he had thought that his enemy was pursuing him. "I tell you I was glad when I found that it was the police," added Taylor. The jury failed to agree, and Taylor was again released on bond. At his second trial the jury returned a verdict of not guilty, and he walked out of court free to continue his criminal career.

In connection with the robbery of Mr. T. R. V. Berriman, a bank manager, at Glenferrie, on October 8, 1923, a house in Barkly street, St. Kilda, was raided by 12 detectives before dawn a few mornings after the crime had been committed. Angus Murray, who was later convicted of the murder of Mr. Berriman and executed, was discovered in the house and apprehended, and in another room of the same house Taylor and a woman were found. Taylor then gave his age as 35. He was charged at St. Kilda with having been the occupier of a house frequented by thieves, and was remanded on bail of £1,000. On October 18, at the same court, he was charged with having harboured Angus Murray, who had broken from the Geelong gaol. Detective Clugston then said that the police believed that Taylor was "the organiser of a gang of murderous ruffians." Additional bail was granted and while he was on remand he was rearrested and charged at the City Court with having been an accessory both before and after, to the felony at Glenferrie, on the day that Murray was charged with murder. Bail for Taylor was refused, in spite of two applications to the Practice Court and then followed a long series of remands, both at the City Court and at the St Kilda Court. In all, Taylor was remanded 31 times on these charges, and after many protests bail was allowed. On November 1, while he was in gaol, his wife sued for divorce on the ground of misconduct, and proceedings were postponed during the hearing of the murder trial. A decree nisi was granted on February 4, 1924.

At the coroner's inquest, Taylor was named as an accessory and he was granted bail at the Criminal Court. He was re-arrested and fined at the St. Kilda Court for using threatening words; and almost two months after when the trial of Murray began, it was decided at the Criminal Court that the charge of having been an accessory would be withdrawn. The trial on the harbouring charge dragged on, and late in March he was imprisoned for six months. It was requested then that he be declared an habitual criminal, but Judge Dethridge, before whom the application came some time later, said that as in the last 10 years he had had no convictions he would give him a chance, and the order was not made.

His last conviction was in January, 1926, for illegal betting. A constable who had often come into contact with Taylor described him as a "doormat thief," who had from petty crimes worked his way into the underworld, where his long career of crime began.

John Daniel Cutmore had had 18 convictions recorded against him since 1914. Known as "Snowy" Cutmore, he had also appeared under various aliases, including that of John McLaughlin, John Nolan, John Watson, and John Harris. His longest sentence was 12 months in Sydney in 1923 for thieving. His offences included assaulting the police, shooting with intent to do grevious bodily harm, and thieving. While in gaol in Victoria he gave little trouble to the authorities, but was a source of considerable worry to the detectives, who, while suspicious, were very often unable to obtain convictions. He was said to have usually carried a revolver, and was suspected of more than one "hold-up." In police circles he was regarded as a dangerous criminal, whose cleverness enabled him to escape the consequences of many crimes.

In 1915 Cutmore was suspected of having been associated with the murder of a sailor in Melbourne. He was presented for trial, and was found not guilty. He joined the Australian Imperial Forces, but did not leave Victoria. He gave a great deal of trouble to the military authorities, and served sentences on various occasions in Geelong and other gaols, and also in Langwarrin.

- From Argus (Melbourne), 28 October 1927, pp 15-16

-----

Father's Name: John Samuel Cutmore

Mother's Name: Bridget Delia McLaughlin Cutmore

∼John Cutmore, was a notorious and violent Australian criminal best known as leader of the Fitzroy Gang, a member of the Tilly Devine's Sydney razor gang, and for his part in the death of Norman Bruhn and Squizzy Taylor. Wikipedia

----

Hoodlums did society a favour by blasting each other to death.

The kingpin of the Melbourne underworld for years after the end of World War 1 was a bowler-hatted, diminutive figure named Joseph Theodore Leslie "Squizzy" Taylor.

One evening in 1927, he went gunning for "Snowy" Cutmore, a rival gangland boss, who was reportedly lying ill in bed with flu, barely able to lift his head. Revolver in hand, he invaded Cutmore's sick room, unaware that his suspected victim had prepared himself for trouble with a gun under the pillow.

In the gun duel that erupted in the bedroom of a squalid Carlton slum house, Cutmore put a shot near Taylor's heart before falling back dead with a bullet in his brain. Taylor staggered out but died shortly after in Melbourne's St Vincent's Hospital – and two of Australia's most vicious criminals had cancelled each other out.

Back when the roaring twenties dawned, a former New York criminal, Lew "The Count" Stirling had arrived on the scene and ruled Melbourne's Fitzroy gang. As his chief aide and enforcer, The Count had enlisted John Daniel "Snowy" Cutmore, a 90kg local bruiser and hold-up man, who was ruthless, tough and violent. He was notorious in Fitzroy as a crazy brawler in brothels and drinking dens. In his half-drunken rages, he was like a wild animal, once branding a reluctant prostitute with a hot iron.

There was bitter open warfare between the Fitzroy gang and Squizzy Taylor's gang for years. Hit-and-run shooting affrays flared and there were constant brawlings and knifings.

By 1923, The Count was in prison and Snowy Cutmore had fled to Sydney to join up with one of the infamous razor gangs operating there. In 1927, Snowy Cutmore arrived back in Melbourne. Word flashed through the underworld that he had come to shoot Squizzy Taylor and take over the Melbourne rackets. In fact, Snowy had quit Sydney because police had him marked down as a prime suspect for the murder of another Melbourne hoodlum, Norman Bruhn, in a Darlinghurst lane.

Squizzy decided to get in first and shoot Cutmore. But instead of deputing someone else to do the job, he went gunning for his old enemy himself, so sure of his power that he believed he could get away with murder, even before witnesses.

Late on the afternoon of October 27, armed with a revolver and accompanied by two of his followers, Taylor went looking for Cutmore in several Melbourne hotels he frequented. Someone whispered to him that Cutmore was in bed at his mother's house, hardly able to lift his head because of influenza. Taylor took a taxi to one of a terrace of four slum dwellings in Barkly St, Carlton, where Snowy's mother lived. Cutmores sister answered the door. Squizzy brushed past her and walked down a passage to a room at the rear where Cutmore lay on a double bed in the gloom, waiting for his mother to poultice his chest. Gun in hand, Taylor burst into the room and began shooting at what he thought was an unarmed man. But Cutmore whipped a revolver from beneath his pillow and returned the fire. Snowy's mother rushed in and fell with a bullet from her son's own gun. The battle continued until both revolvers were empty.

Leaving Cutmore dead from five bullets, Taylor, with blood pouring from his wounds, managed to get back to the street and fall into the taxi. His companions ordered the driver to rush him to hospital. Squizzy died soon after arrival and so one vicious gun duel had rid Melbourne of two of the most dangerous criminals in Australia.

From: "Daily Mirror" (Sydney) Wednesday February 28th 1990

-----

John Daniel Cutmore had had 18 convictions recorded against him since 1914. Known as "Snowy" Cutmore, he had also appeared under various aliases, including that of John McLaughlin, John Nolan, John Watson, and John Harris. His longest sentence was 12 months in Sydney in 1923 for thieving. His offences included assaulting the police, shooting with intent to do grevious bodily harm, and thieving. While in gaol in Victoria he gave little trouble to the authorities, but was a source of considerable worry to the detectives, who, while suspicious, were very often unable to obtain convictions. He was said to have usually carried a revolver, and was suspected of more than one "hold-up." In police circles he was regarded as a dangerous criminal, whose cleverness enabled him to escape the consequences of many crimes.

In 1915 Cutmore was suspected of having been associated with the murder of a sailor in Melbourne. He was presented for trial, and was found not guilty. He joined the Australian Imperial Forces, but did not leave Victoria. He gave a great deal of trouble to the military authorities, and served sentences on various occasions in Geelong and other gaols, and also in Langwarrin.

- Melbourne Argus, October 28, 1927

-----

As a sequel to what is believed to have been a private feud of long standing, two men were shot dead, and a woman was seriously injured in a house in Carlton early last night. They were:-

Dead

- Taylor, Joseph Theodore Leslie (known as "Squizzy"), aged 43 years, of Darlington street, Richmond.

- Cutmore, John, aged 38 years, of Barkly street, Carlton.

Wounded

- Cutmore, Bridget Delia, aged 58 years, of Barkly street, Carlton, mother of John Cutmore.—Suffering from a bullet wound in the right shoulder. Admitted to the Melbourne Hospital.

Hailing a taxi-cab in Lonsdale Street at 5 o'clock yesterday evening, Taylor, accompanied by two men, ordered the driver, John William Hall, to go to Carlton. When he engaged the cab Taylor gave no indication of his destination beyond saying that he wished to visit an hotel in Carlton. Calls were made to several hotels in the vicinity of Rathdown, Lygon, and Elgin streets. The movements of the men indicated that they were in search of another person or persons. Their conversation, however, gave no clue as to whom they were seeking. Eventually Taylor told the driver to go to Barkly Street. Turning from Rathdown Street the cab had only travelled a few yards in a northerly direction along Barkly street, when the driver was told to stop. Taylor, accompanied by one of his friends left the cab, and walking some distance along the northern side of the street went into one of a terrace of houses. The third man, as far as is known, remained in the car.

When they reached the house the front door was open. The occupants were accustomed to strangers entering—some of the rooms are occupied by lodgers—and no attention was attracted as Taylor and his companion walked through the house to a small room at the rear, where Cutmore was lying in bed, suffering from an attack of influenza. According to statements made to the police, only a few words were spoken but these were indistinguishable. Suddenly the attention of Mrs. Bridget Cutmore, the mother of the dead man, was attracted by the report of a revolver shot. Other shots followed in quick succession. Hurrying to the room, Mrs. Cutmore saw two men, one of whom was holding a revolver. Her son had not left his bed. While she stood in the doorway she received a shot in the right shoulder. Although in a dazed condition she recollects that one man left the house by the front door, while the second man ran into the back yard, presumably leaving by a gate leading to a lane.

Taylor staggered towards the car, which was waiting in the street, and exclaimed, "I am shot. Take me to hospital." His companion helped him into the car, and told the driver to hurry to St. Vincent's Hospital. Travelling by way of Johnston Street the car was delayed for some minutes in a traffic crush at the intersection of Brunswick street. Apparently disregarding the serious condition of his friend, Taylor's companion opened the door of the motorcar—a sedan—and jumping out, said to the driver, "You had better see this through yourself." He disappeared down Brunswick street. Realising that no time should be lost in getting his passenger to the hospital, Hall hurried to St. Vincent's Hospital. Taylor was assisted into the casualty ward, where he was found to be unconscious. His death occurred 20 minutes later. An examination showed that Taylor had received a bullet wound on the right side below the ribs.

Occurring at a time when it was thought that any feuds which had existed among members of the criminal class had been buried, the shooting created a sensation at police headquarters, and revived memories of the Fitzroy vendetta. The police have no definite knowledge of the cause of the rivalry between Taylor and Cutmore. It is said, however, that jealousy concerning a woman was the main reason of their enmity. Cutmore, who was well known to the police, left Melbourne some months ago, and with his wife took up residence in Sydney. He returned to Melbourne last Sunday with his wife and went to live with his mother in Barkly Street, Carlton. It is known that he visited the Richmond racecourse in company with a man who is said to have occupied a room as a lodger in the house in Barkly Street. Since then, however, he had been confined to bed with a severe attack of influenza. It is assumed that Taylor, hearing of his return from Sydney, set out yesterday evening with the object of finding him.

The house in which the Cutmores lived is one of a terrace of four old-fashioned brick cottages on the northern side of Barkly street, about 50 yards from the corner of Rathdown street. The dwelling is single-fronted, abutting on to the footpath. The main rooms of the house are reached from a narrow passage leading from the front door to a doorway giving access to the back yard. The room occupied by Cutmore yesterday is at the extreme rear of the house, and was neatly furnished. It had one window, facing the back yard. A peculiar feature of the shooting is that, although there are houses adjoining the Cutmore's home on either side, the attention of no one in the vicinity was attracted by the shots.

When news of the affair became public, mainly through the arrival of the police and ambulances, much excitement and speculation about the cause of the deaths of the two men was evident, and for many hours the Cutmore's home was the object of the curiosity of a large crowd.

Although her condition is considered serious Mrs. Cutmore was well enough last night to be interviewed by Detective-sergeants Davey and Brophy in No. 6 ward at the Melbourne Hospital. In her statement she was unable to say much of the tragedy which involved the death of her son.

"I was in the kitchen preparing the evening meal," said Mrs Cutmore, "when I heard footsteps in the passage. I took no notice, as some of the rooms in the house are let to lodgers, and I thought perhaps it was one of them returning home. It also occurred to me that it might have been one of the many friends who had called to see my son since he returned from Sydney. The front door had been left open by my son's wife, who had left the house to buy some milk at a shop near by. Shortly after I heard the footsteps in the passage I heard men's voices in my son's bedroom. The words were not distinct, but I did not think that there was a quarrel. Suddenly I heard two shots. While hurrrying into my son's room I heard several more shots, and on opening the door I saw two men standing at the end of his bed, which faced towards the back yard. Before I could even see my son another shot was fired and I felt a sharp pain in my right shoulder. I was dazed for the moment, and so unexpected was the whole affair that I cannot say which of the two men was carrying a gun, nor did I see that one of the men was seriously wounded. They both brushed past me into the passage, and one ran out of the back door, while the other seemed to stagger up the passage towards the front door. In the bedroom I saw my son lying on the bed. It seemed only a few minutes before the police arrived and I was taken to the hospital."

A pathetic incident occurred at the end of the interview of Mrs. Cutmore by the detectives at the hospital last night, when she was told of her son's death. Apparently she knew that he had been wounded, and asked Detective-sergeant Brophy if he was seriously ill. When told that he had been shot dead Mrs. Cutmore was obviously affected.

An X-ray examination of Mrs. Cutmore is to be made this morning, and it is expected that an operation for the removal of the bullet will be carried out during the day.

From descriptions given to the police, it is apparent that Taylor's companion, who left the house by the back door, is identical with a man who hurried to the surgery of Dr. McCutcheon, in Rathdown Street, and told him of the shooting, and later went to the Carlton police station for assistance. He then disappeared, and up till a late hour last night had not been traced by the detectives. Search was also made in the city and suburbs for the second man, who jumped out of the taxi-cab at the corner of Brunswick and Johnston streets, Fitzroy. In their efforts to find these men from the meagre descriptions which had been supplied, a large party of detectives visited the hotels in the Carlton district at which the taxi-cab had called during the afternoon. They were, however, unable to trace either of Taylor's companions.

An extraordinary feature of the tragedy which is engaging the close attention of the detectives is the fact that one of the revolvers used in the duel has disappeared. A .32 automatic six-chambered pistol, which was empty, was found in Taylor's possession when a Fitzroy constable searched his clothes at St. Vincent's Hospital. Reconstructing the duel last night, Sub-inspector Piggott advanced the theory that, of the succession of shots in the bedroom, Taylor fired six, as the chambers of his pistol were empty. That the shots were fired by each man simultaneously is indicated from an examination made last night by the police of Taylor's weapon. Evidently a bullet from Cutmore's revolver struck the barrel of Taylor's pistol, and, glancing off, inflicted a flesh wound in the little finger of his right hand. Part of the nickel cap of a bullet, apparently from Cutmore's revolver, had become jammed in one of the chambers.

From his youth the life of Leslie Taylor was a sordid record of criminality. Taylor, who affected smartness of dress and "polish" in his dealings with the police force, delighted to surround himself with an air of mystery and cleverness. By his spectacular exploits he came to be regarded as a master-mind among criminals. This reputation was not well-founded. Taylor was a criminal of ordinary mentality, whose distinguishing features were his callous disregard for the lives of others, his treachery towards his associates, and his personal cowardice.

Leslie Taylor, alias Leslie Grout, alias Michael McGee, was born at Brighton in 1884, and was one of the family of five brothers and two sisters. After receiving a state school education he worked for three years in a training stables, and from then on, so far as is known, he did no honest work. His early criminal record included imprisonment for 21 days for larceny in 1896, and imprisonment on no less than five occasions in 1907 on minor charges. Subsequent offences for which he received sentences included larceny, assault, vagrancy, stealing from the person, and obstructing the police. His total convictions until 1916 numbered 18.

The robbery and murder of a commercial traveller, Mr. Arthur Trotter, at his home at Fitzroy, on January 7, 1913, for which Harold Thompson, a labourer, was tried, was committed by three men, one of whom the police believe was Taylor, although no direct evidence could be obtained. Thompson was arrested after a reward had been offered and the chief evidence against him consisted of finger prints. It was considered that this evidence was insufficient, and the prisoner was acquitted.

Late on the night of February 28, 1916, the garage manager of the Globe Motor and Taxi Company was called by telephone by a man who said that his name was Lestrange, and ordered a car for the following day to take him to Eltham. He asked for the number of the car, and particularly requested that it should not be of a certain make. The order was booked, and on the following day William Haines, who was a relieving driver only, was sent to the address given. He left the garage at five minutes to 8 o'clock in the morning, and nothing more was heard of him until late on the same night his body was found huddled on the floor of his car at the junction of Bulleen and Templestowe roads, at Heidelberg. The body had been covered by a motor rug and hidden from view. Bullet wounds in the head and neck showed that Haines had been a victim of a cold-blooded and diabolical crime, for which the entire absence of apparent motive baffled the detectives engaged on the case. The car had been noticed by people at the side of the road several hours before the body of Haines was discovered. A fortnight after the discovery of the body, Taylor and another man were charged with the murder. When charged, Taylor broke into tears and explained that he did not murder anybody. Earlier in the day both men had been brought before the City Court and sentenced to imprisonment for 12 months on charges of vagrancy. Their trial for murder began on April 18, when the Crown case was that the accused had intended to rob a bank manager who was taking bank money from Doncaster to Templestowe. It was the belief of the police that Taylor and his accomplice, intending to make Haines drive them to a suitable spot where they could disguise themselves, and that they evidently expected that the promise of a substantial share in the booty would have induced Haines to assist in the crime. It was found that a grave had been prepared at Clayton, several miles away, and the theory was that the body of the bank manager was to be placed in this grave. Among the witnesses for the prosecution was the matron at the City Watchhouse, who repeated conversation concerning identification between the prisoners which she had overheard. During this conversation Taylor had said, "They can't very well pot us. They can't identify us." In his summing up, Mr. Justice Hood told the jury that the evidence of identification showed simply that one of the murderers was tall, and the other short, and he added that if the jury believed the story for the defence it was extremely strong. Taylor and the other man were found not guilty.

Taylor appealed against his sentence of 12 months for vagrancy, but on the evidence of several detectives that he was a known associate of criminals and undesirable characters, the appeal was dismissed. A second appeal by Taylor against the sentence for obstructing the police in the execution of their duty was also dismissed.

The "Fitzroy Vendetta," as it was known, which lasted for many months in 1919, formed one of the most extraordinary chapters of Taylor's sordid career. The vendetta arose, it is believed, from a quarrel among a number of criminals over the disposal of jewellery obtained in a carefully planned robbery of a Collins street jeweler's shop. Some months after the robbery a woman associated with one of the criminals appeared at an "underworld" party wearing a quantity of jewellery which other guests recognised as a portion of the haul to which they considered that they were entitled. For months afterwards there was a bitter war between opposing parties of criminals, one of which Taylor was supposed to lead. The victims in these affrays never sought the assistance of the police and when they were so seriously injured that the police were able to interview them, they maintained an obstinate silence regarding the identity of their assailant. One man was brought to hospital in the early hours of the morning with six bullet wounds in his head. He recovered. Other shootings occurred, but no one was killed, and eventually the feud died.

In 1921 Taylor absconded from bail of £300, which had been fixed in connection with a charge against him of having broken and entered a warehouse and bond store in King street. For more than 12 months the police searched for him unsuccessfully. During the 14 months that he was in hiding many messages had come from him to the police promising to give himself up when he was ready. The eventual surrender was carefully arranged between Taylor's friends and the detectives. Punctually at a quarter past 8 o'clock on the morning of Thursday 22, 1922—the night arranged with the police—a large motor-car stopped outside the detective office. Taylor stepped out, paid the chauffeur. He told the detectives that he had never had any intention of running away. He added that he had spent most of his time in a flat in East Melbourne, and he told the police that he had often come out of hiding in disguise and had attended several race meetings sometimes dressed as a woman, but more often as a schoolboy in knickers. Taylor was a "showy" criminal, who thought a great deal of impressing members of the underworld, and the detectives were sceptical about the truth of the story. He was again committed for trial on the charge of having entered the warehouse, and was once more released on bail. His trial took place early in October. On the day before it took place a man who was walking up Bourke street about 8 o'clock in the evening fired three shots at Taylor as he alighted from a motor-car near the entrance to the Bookmakers' Clerks' Association. Alarmed pedestrians ran in all directions. Taylor was shot in the right leg, and fearing that further shots would be fired limped across the footpath and was assisted into the motor-car. Taylor's assailant escaped as soon as the shot had been fired, but later a man was arrested on a charge of having shot at Taylor. Taylor limped into the dock on crutches to answer the charge of entering the warehouse and in answer to the charge he said that he had been drinking heavily, and that an enemy of his had challenged him to fight. Running away he had entered the warehouse, and when he heard the police whistle he had thought that his enemy was pursuing him. "I tell you I was glad when I found that it was the police," added Taylor. The jury failed to agree, and Taylor was again released on bond. At his second trial the jury returned a verdict of not guilty, and he walked out of court free to continue his criminal career.

In connection with the robbery of Mr. T. R. V. Berriman, a bank manager, at Glenferrie, on October 8, 1923, a house in Barkly street, St. Kilda, was raided by 12 detectives before dawn a few mornings after the crime had been committed. Angus Murray, who was later convicted of the murder of Mr. Berriman and executed, was discovered in the house and apprehended, and in another room of the same house Taylor and a woman were found. Taylor then gave his age as 35. He was charged at St. Kilda with having been the occupier of a house frequented by thieves, and was remanded on bail of £1,000. On October 18, at the same court, he was charged with having harboured Angus Murray, who had broken from the Geelong gaol. Detective Clugston then said that the police believed that Taylor was "the organiser of a gang of murderous ruffians." Additional bail was granted and while he was on remand he was rearrested and charged at the City Court with having been an accessory both before and after, to the felony at Glenferrie, on the day that Murray was charged with murder. Bail for Taylor was refused, in spite of two applications to the Practice Court and then followed a long series of remands, both at the City Court and at the St Kilda Court. In all, Taylor was remanded 31 times on these charges, and after many protests bail was allowed. On November 1, while he was in gaol, his wife sued for divorce on the ground of misconduct, and proceedings were postponed during the hearing of the murder trial. A decree nisi was granted on February 4, 1924.

At the coroner's inquest, Taylor was named as an accessory and he was granted bail at the Criminal Court. He was re-arrested and fined at the St. Kilda Court for using threatening words; and almost two months after when the trial of Murray began, it was decided at the Criminal Court that the charge of having been an accessory would be withdrawn. The trial on the harbouring charge dragged on, and late in March he was imprisoned for six months. It was requested then that he be declared an habitual criminal, but Judge Dethridge, before whom the application came some time later, said that as in the last 10 years he had had no convictions he would give him a chance, and the order was not made.

His last conviction was in January, 1926, for illegal betting. A constable who had often come into contact with Taylor described him as a "doormat thief," who had from petty crimes worked his way into the underworld, where his long career of crime began.

John Daniel Cutmore had had 18 convictions recorded against him since 1914. Known as "Snowy" Cutmore, he had also appeared under various aliases, including that of John McLaughlin, John Nolan, John Watson, and John Harris. His longest sentence was 12 months in Sydney in 1923 for thieving. His offences included assaulting the police, shooting with intent to do grevious bodily harm, and thieving. While in gaol in Victoria he gave little trouble to the authorities, but was a source of considerable worry to the detectives, who, while suspicious, were very often unable to obtain convictions. He was said to have usually carried a revolver, and was suspected of more than one "hold-up." In police circles he was regarded as a dangerous criminal, whose cleverness enabled him to escape the consequences of many crimes.

In 1915 Cutmore was suspected of having been associated with the murder of a sailor in Melbourne. He was presented for trial, and was found not guilty. He joined the Australian Imperial Forces, but did not leave Victoria. He gave a great deal of trouble to the military authorities, and served sentences on various occasions in Geelong and other gaols, and also in Langwarrin.

- From Argus (Melbourne), 28 October 1927, pp 15-16

-----

Father's Name: John Samuel Cutmore

Mother's Name: Bridget Delia McLaughlin Cutmore

∼John Cutmore, was a notorious and violent Australian criminal best known as leader of the Fitzroy Gang, a member of the Tilly Devine's Sydney razor gang, and for his part in the death of Norman Bruhn and Squizzy Taylor. Wikipedia

Inscription

In Loving Memory of

Catherine King

Died 19th Sept. 1918

John Daniel Cutmore

Died 27 Oct. 1927

Bridget Cutmore

Died 15th April 1938

Family Members

Sponsored by Ancestry

Advertisement

Advertisement