Many of the details from Alabama's life story came directly from Larry Wells, second husband of the late Dean Faulkner-Wells. Dean Faulkner-Wells was William's niece. Her father, Dean Swift Falkner, from whom her namesake comes, died flying a plane that was given him by William Faulkner himself. This lay heavily on William's conscience, and William brought Dean Swift's remains home and buried him in one of the three Falkner family plots in St. Peter's Cemetery, all of which are located in the southern portion of Section 6. This explains in more depth why the Biblical reference left on Dean Swift Falkner's grave was chosen and from whom the scripture reference originated.

William Faulkner obtained legal guardianship of Dean's daughter, Dean, and raised her at his home--which he christened "Rowan Oak"--in Oxford (MS). When Dean Faulkner-Wells (William's niece) passed away in recent years (2011), she was buried up the hill a pace at the southern edge of Section 5 in Oxford Memorial Cemetery. Dean Faulkner-Wells was born 5 years after her cousin Alabama's death, but grew up often visiting Alabama's gravesite with William & Estelle, and she later passed this knowledge onto her husband, Larry Wells. Alabama's grave has looked the same since the time Larry Wells moved to Oxford in the 1970's.

To clear up any confusion between family surname spellings, William Faulkner added the "U" to his family name while he was training as a pilot in Canada in the Air Corps during WWI (Source: "Faulkner Country" pamphlet from the Oxford, Mississippi Convention & Visitors Bureau). However, William and his descendants still originate from the "Falkner" family.

William & Estelle are buried in the SW corner of Section 2 of Oxford Memorial Cemetery (a.k.a. St. Peter's, Section 8 by the Skipworth Genealogical Society which transcribed graves from St. Peter's and some of the adjoining cemeteries in the mid- to late-1970's). The couple's graves are located on a cement platform on the north side of a hill (which defines part of the border line between St. Peter's & Oxford Memorial Cemeteries). It is also marked by a green state historical marker found 20 paces west of the platform along the sidewalk on the east side of 16th Street. William Faulkner was one of the first to be buried in Oxford Memorial when the cemetery first opened in the early 1960's. Cemetery boundary lines remained unclear and were not officially cleared up or settled by the city of Oxford until 2007, around the time of St. Peter's sesquicentennial (150th anniversary) celebration. A thirty page book was written on St. Peter's and specifically deals with the questions surrounding the four cemeteries, and includes a map of some of the cemetery boundary lines on the final page. It is available in the genealogical room at the Lafayette County Library which is only 5-6 blocks from the cemeteries. St. Peter's relinquished their cemetery to the Oxford Public Works Department the following year (in 2008), and the city has maintained the cemetery and its namesake to present-day.

At this time, I'd like to thank Bill Griffith, curator of Rowan Oak, for all of the assistance he has provided in helping me learn about William Faulkner's family and the details of Alabama's life. To Louis Bourgeois, Executive Director of VOX, for our chance-meeting in which he in turn introduced me to his friend, Larry Wells. And to Larry Wells, who as one of the few in Oxford who still knew the location of Alabama's gravesite, brought me over to her grave and shared many new intimate details about Alabama's life story with me. I'd like to thank Dana Caruthers Norton whose photo request got me started on the 7-month journey that led to discovering the whereabouts of Alabama's grave in the first place. And finally, special thanks to Kathy Bergold who transferred management of Alabama's virtual memorial to me when I wasn't even asking for it, but only hoping to ensure her that my photos of the gravesite where authentic (and not just some random pictures of the ground). I hope that I have in turn done my best to do Alabama's memory justice in regards to research and preparation for this virtual memorial and bio.

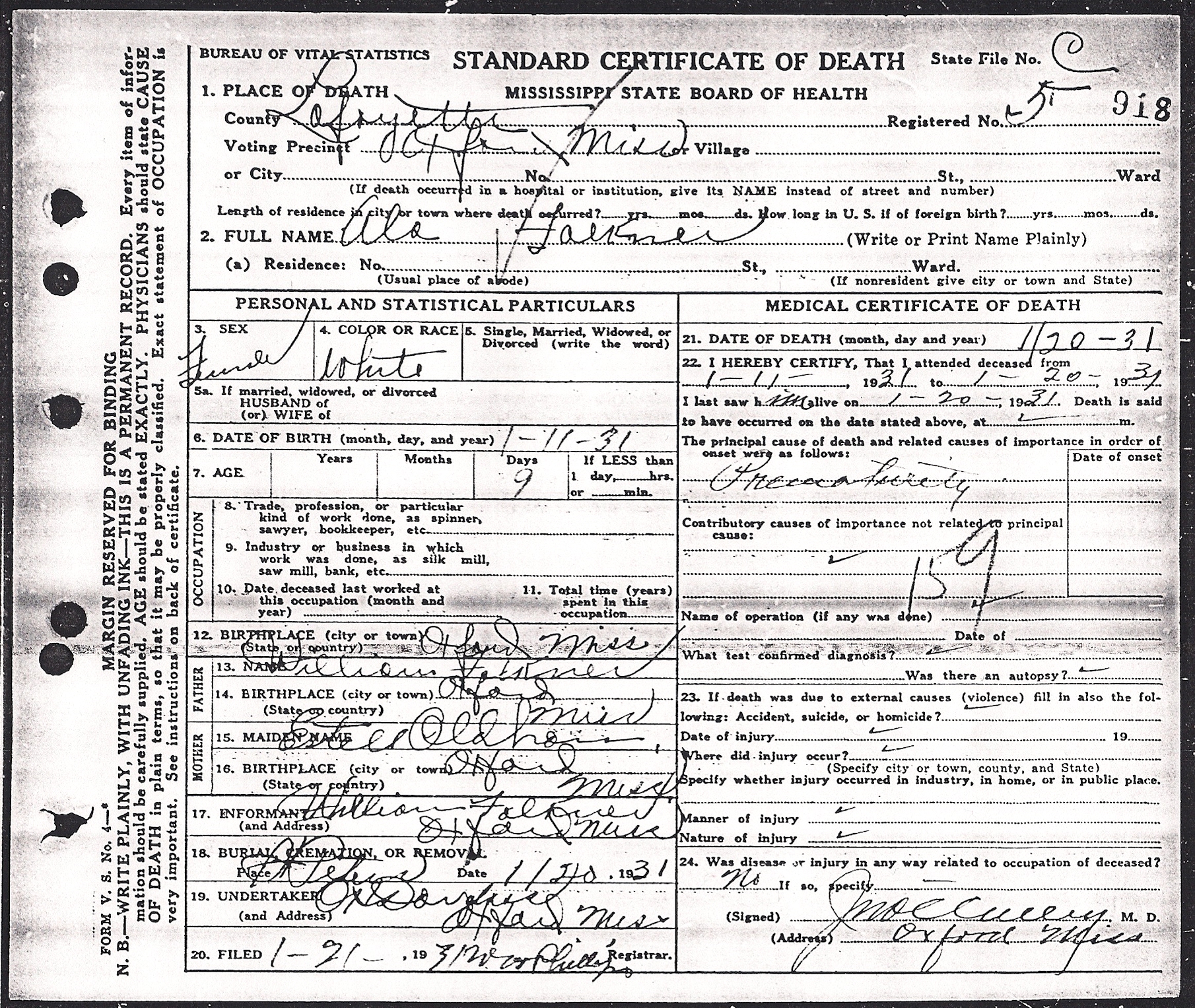

No photos of Alabama Faulkner have yet been found, according to Bill Griffith & Larry Wells (and likely may not exist after learning about the family circumstances surrounding Alabama's short life). In lieu of not having an available photo to share of Alabama, I drove out to the Mississippi Department of Archives and History in Jackson (MS) as part of one of my own genealogical hunts and obtained a copy of her death certificate to authenticate the details of her life story which you are now reading. I have shared a copy of the death certificate with all interested parties whom I have been in touch with during this research process.

I personally learned many of the details of Alabama's life and the family situations through word-of-mouth by reliable sources (as stated above) before having read the biographical excerpts presented below. Many of the family details not found below were weaved into the storyline above. Most of the family burial locations listed above have been found while walking St. Peter's, Oxford Memorial, and the other three adjoining cemeteries in efforts to fulfill several other photo requests for folks over the past two years. If you'd like a copy of Alabama's death certificate, want to learn more about the cemetery histories, or would like copies of any of the available cemetery maps, please feel free to check out my profile and contact me from there. I will be glad to share any information I can that will be of help!

Finally, I'd like to offer a little extra history to put the following two book excerpts into historical context and shed light on the remainder of the family story surrounding the life of Alabama Faulkner. The Great Depression was only 13 months strong at the time of Alabama's short life in January 1931 and William and Estelle were struggling newlyweds in a newly bought home. Memphis (TN) is only an hour NW of Oxford (MS) in today's economy due to the introduction of the Dwight D. Eisenhower Interstate System in 1956, but only U.S. Highways (i.e.- U.S. 51, U.S. 78) and state highways existed back in those days. Motorcars were also available in 1931 but mass production through the assembly line process was not even two decades old yet. Motorcars were not cheap and had not yet reached peak popularity or availability. William and other Falkner family members did indeed personally own their own automobiles during Alabama's short life span.

Thank-you for your time. Have a blessed day & enjoy the proceeding biographical family excepts!

~Everett Baranowski (06/06/2015)

UPDATE: Alabama Faulkner's full grave was recently unearthed in the past couple of months by an unknown source. I contacted Larry Wells, and he was even unaware that the grave had been unearthed. Updated photographs have been uploaded. (04/29/2016)

Excerpt taken from pp. 173-174 of Chapter 30 of "Faulkner: A Biography," ©2005 Joseph Leo Blotner:

"When Estelle woke Bill [William] on the bitter-cold night of Saturday, January 10, 1931, he thought she was imagining things; the baby wasn't due for two months. But he telephoned ahead and drove Estelle to Dr. Culley's hospital. The next day she gave birth to a tiny little girl with beautiful features. They named her Alabama, and on Tuesday, Faulkner sent the news by telegram to her namesake in Memphis. Estelle was too ill even to see the baby, but Faulkner wanted her and their daughter at home as soon as possible. There was no incubator at the hospital, and with a trained nurse for Alabama and practical nurse for Estelle, he thought they would do just as well at Rowan Oak. John Culley was a good-looking, dogmatic man whom Faulkner did not particularly like, but he was a fine doctor and his wife, Nina, was one of Estelle's best friends. He came every day because there were problems with the baby's digestive system. At the end of the week he could see that Alabama's condition was worsening. Faulkner and Dean [William's brother] went to Memphis for an incubator, but it was too late. On Tuesday afternoon, January 20, the baby died. Estelle had never seen her.

The family drove in three cars to St. Peter's Cemetery, and in the cold January morning Murry Falkner [William's father] prayed over the small grave. He was usually abrupt and inarticulate, but Sallie Murry remembered that now he offered a beautiful prayer. That afternoon the nurse brought Estelle a sedative. Then Bill came in and sat beside the bed. He told her about Alabama and wept—the first time she had ever seen him cry. She told him they would have another child.

"Bill," she said, "get you a drink."

"No," he said. "This is one time I'm not going to do it." Later Mr. Murry [Faulkner's father] came to see her. The baby had looked like Billy, he said. Billy had held the casket on his lap all the way to the cemetery.

As he had promised, Faulkner did not turn to liquor, not immediately. But there was one curious aftermath: it was a persistent rumor in Oxford that Faulkner had shot Dr. Culley in the shoulder. Estelle thought that Dr. Culley was in no way culpable in Alabama's death, but Faulkner apparently brooded over the lack of an incubator and felt that the child should have had better care. The rumor persisted in various forms. Faulkner had not shot Dr. Culley, but apparently he had wanted to. The rumor had originated with him. One symbolic response was more positive. Not long afterward he made the donation of an incubator—to Dr. Bramlett's hospital, to be used free of charge when parents could not pay for it.

His grief would remain acute for that whole year. …"

Excerpt taken from pp. 77-79 of Chapter 6 (entitled 'Two Brothers') of "Every Day by the Sun: A Memoir of the Faulkners of Mississippi," ©2011 Dean Faulkner Wells:

"When William purchased "the old Bailey place" on Garfield Avenue (now Old Taylor Road), he named the antebellum house and its thirteen acres "Rowan Oak." It was his way of declaring 'This is my private place'. To keep up payment and buy materials for repairs, he churned out stories at a furious pace, submitting thirty-seven in one year, but selling only six.

In midsummer of 1930, the 'Saturday Evening Post' accepted "Red Leaves," a short story whose subject differed from his other Yoknapatawpha sagas. It dealt with the Chickasaw Indians' tribal custom of burying their chiefs with their dogs, horses, and a slave—in this case a body servant not ready to die. The 'Post' paid him $750. Rowan Oak could now have electricity and Estelle a new stove.

Times were not easy for the newlyweds. William could not afford to hire carpenters to repair Rowan Oak, so Dean regularly brought fraternity brothers to help work on the house. They put on a new roof, rewired and expanded electrical circuits, and, thanks to "Red Leaves," put in new fixtures, ceiling lamps, pipes, and plumbing.

In spite of their financial difficulties, Estelle and William were eagerly looking forward to the birth of their first child in March 1931. So were Cho Cho and Malcolm [Estelle's children from her prior/first marriage].

Estelle's doctor, John Culley, was an excellent physician but a man with whom William did not get along. His wife, Nina, was Estelle's best friend. Dr. Culley was extremely concerned about Estelle because of the difficult deliveries of both of her children. In addition, she was weakened by anemia and weighed less than one hundred pounds. He warned her to be careful and prescribed iron and calcium pills for her.

Christmas at Rowan Oak with both their families in attendance was happy but exhausting for Estelle. She woke William late at night on January 10 and told him the baby was coming. At first he did not believe her, but he called Dr. Culley and asked him to meet them at the hospital. She gave birth the next day to a small, perfectly formed baby girl. They named her Alabama in honor of William's Aunt Bama. He wanted his wife and child at home, believing that since there was no incubator at Dr. Culley's hospital, they would be cared for just as well at Rowan Oak with a trained nurse for Alabama and a practical nurse for Estelle, who was too sick to care for the infant. Dr. Culley noticed that the baby had problems with her digestive tract. By the end of the week, this dilemma became life threatening. She was tiny and weak and could not retain any milk.

William was frantic. He tried everything, first hiring a wet nurse, then begging Dean to find a goat. Maybe the baby could digest goat milk. Within hours Dean brought one to Rowan Oak. The brothers took turns milking it and carrying the precious milk to the house. Nothing had prepared William for this terrible, grinding fear. The practical nurse tried to feed the milk to Alabama; then William tried, then Dean. She could not keep it down.

Dr. Culley suggested an incubator and William, desperate to get his hands on one but not trusting himself to drive, asked Dean to take him to Memphis. They drove in the middle of the road at top speed, passing every vehicle. They got an incubator and brought it back to Oxford—only to find the infant fading before their eyes. Dean sat up with William and Estelle all night. The next day, January 20, Alabama died. The Faulkners mourned as one. A private service was held at Rowan Oak and William read from the Bible. Dean drove to the cemetery while his brother cradled the tiny casket in his lap and wept. The rest of the family followed in two cars. It was bitter cold. At the gravesite, as his only granddaughter was laid to rest, Murry said a prayer that has been described as eloquent. William's grief staggered him. Soon after Alabama's death he donated an incubator to a second hospital in Oxford to be used free of charge by anyone in need."

Immediate Family & Household Relations-

William Faulkner (father) / Memorial #326

Estelle Oldham-Faulkner (mother) / 13603052

Malcolm Franklin (½ brother) / 13603167

Victoria "Cho Cho" Franklin (½ sister) / ???

Jill Faulkner-Summers (sister) / 57457345

Murry Falkner (gr father) / 35363577

Maud Butler-Faulkner (gr mother) / 35363614

Dean Swift Falkner (uncle) / 35363765

Dean Faulkner-Wells (first cousin) / 74049021

Caroline "Callie" Barr-Clark

(family servant) / 69850973

Many of the details from Alabama's life story came directly from Larry Wells, second husband of the late Dean Faulkner-Wells. Dean Faulkner-Wells was William's niece. Her father, Dean Swift Falkner, from whom her namesake comes, died flying a plane that was given him by William Faulkner himself. This lay heavily on William's conscience, and William brought Dean Swift's remains home and buried him in one of the three Falkner family plots in St. Peter's Cemetery, all of which are located in the southern portion of Section 6. This explains in more depth why the Biblical reference left on Dean Swift Falkner's grave was chosen and from whom the scripture reference originated.

William Faulkner obtained legal guardianship of Dean's daughter, Dean, and raised her at his home--which he christened "Rowan Oak"--in Oxford (MS). When Dean Faulkner-Wells (William's niece) passed away in recent years (2011), she was buried up the hill a pace at the southern edge of Section 5 in Oxford Memorial Cemetery. Dean Faulkner-Wells was born 5 years after her cousin Alabama's death, but grew up often visiting Alabama's gravesite with William & Estelle, and she later passed this knowledge onto her husband, Larry Wells. Alabama's grave has looked the same since the time Larry Wells moved to Oxford in the 1970's.

To clear up any confusion between family surname spellings, William Faulkner added the "U" to his family name while he was training as a pilot in Canada in the Air Corps during WWI (Source: "Faulkner Country" pamphlet from the Oxford, Mississippi Convention & Visitors Bureau). However, William and his descendants still originate from the "Falkner" family.

William & Estelle are buried in the SW corner of Section 2 of Oxford Memorial Cemetery (a.k.a. St. Peter's, Section 8 by the Skipworth Genealogical Society which transcribed graves from St. Peter's and some of the adjoining cemeteries in the mid- to late-1970's). The couple's graves are located on a cement platform on the north side of a hill (which defines part of the border line between St. Peter's & Oxford Memorial Cemeteries). It is also marked by a green state historical marker found 20 paces west of the platform along the sidewalk on the east side of 16th Street. William Faulkner was one of the first to be buried in Oxford Memorial when the cemetery first opened in the early 1960's. Cemetery boundary lines remained unclear and were not officially cleared up or settled by the city of Oxford until 2007, around the time of St. Peter's sesquicentennial (150th anniversary) celebration. A thirty page book was written on St. Peter's and specifically deals with the questions surrounding the four cemeteries, and includes a map of some of the cemetery boundary lines on the final page. It is available in the genealogical room at the Lafayette County Library which is only 5-6 blocks from the cemeteries. St. Peter's relinquished their cemetery to the Oxford Public Works Department the following year (in 2008), and the city has maintained the cemetery and its namesake to present-day.

At this time, I'd like to thank Bill Griffith, curator of Rowan Oak, for all of the assistance he has provided in helping me learn about William Faulkner's family and the details of Alabama's life. To Louis Bourgeois, Executive Director of VOX, for our chance-meeting in which he in turn introduced me to his friend, Larry Wells. And to Larry Wells, who as one of the few in Oxford who still knew the location of Alabama's gravesite, brought me over to her grave and shared many new intimate details about Alabama's life story with me. I'd like to thank Dana Caruthers Norton whose photo request got me started on the 7-month journey that led to discovering the whereabouts of Alabama's grave in the first place. And finally, special thanks to Kathy Bergold who transferred management of Alabama's virtual memorial to me when I wasn't even asking for it, but only hoping to ensure her that my photos of the gravesite where authentic (and not just some random pictures of the ground). I hope that I have in turn done my best to do Alabama's memory justice in regards to research and preparation for this virtual memorial and bio.

No photos of Alabama Faulkner have yet been found, according to Bill Griffith & Larry Wells (and likely may not exist after learning about the family circumstances surrounding Alabama's short life). In lieu of not having an available photo to share of Alabama, I drove out to the Mississippi Department of Archives and History in Jackson (MS) as part of one of my own genealogical hunts and obtained a copy of her death certificate to authenticate the details of her life story which you are now reading. I have shared a copy of the death certificate with all interested parties whom I have been in touch with during this research process.

I personally learned many of the details of Alabama's life and the family situations through word-of-mouth by reliable sources (as stated above) before having read the biographical excerpts presented below. Many of the family details not found below were weaved into the storyline above. Most of the family burial locations listed above have been found while walking St. Peter's, Oxford Memorial, and the other three adjoining cemeteries in efforts to fulfill several other photo requests for folks over the past two years. If you'd like a copy of Alabama's death certificate, want to learn more about the cemetery histories, or would like copies of any of the available cemetery maps, please feel free to check out my profile and contact me from there. I will be glad to share any information I can that will be of help!

Finally, I'd like to offer a little extra history to put the following two book excerpts into historical context and shed light on the remainder of the family story surrounding the life of Alabama Faulkner. The Great Depression was only 13 months strong at the time of Alabama's short life in January 1931 and William and Estelle were struggling newlyweds in a newly bought home. Memphis (TN) is only an hour NW of Oxford (MS) in today's economy due to the introduction of the Dwight D. Eisenhower Interstate System in 1956, but only U.S. Highways (i.e.- U.S. 51, U.S. 78) and state highways existed back in those days. Motorcars were also available in 1931 but mass production through the assembly line process was not even two decades old yet. Motorcars were not cheap and had not yet reached peak popularity or availability. William and other Falkner family members did indeed personally own their own automobiles during Alabama's short life span.

Thank-you for your time. Have a blessed day & enjoy the proceeding biographical family excepts!

~Everett Baranowski (06/06/2015)

UPDATE: Alabama Faulkner's full grave was recently unearthed in the past couple of months by an unknown source. I contacted Larry Wells, and he was even unaware that the grave had been unearthed. Updated photographs have been uploaded. (04/29/2016)

Excerpt taken from pp. 173-174 of Chapter 30 of "Faulkner: A Biography," ©2005 Joseph Leo Blotner:

"When Estelle woke Bill [William] on the bitter-cold night of Saturday, January 10, 1931, he thought she was imagining things; the baby wasn't due for two months. But he telephoned ahead and drove Estelle to Dr. Culley's hospital. The next day she gave birth to a tiny little girl with beautiful features. They named her Alabama, and on Tuesday, Faulkner sent the news by telegram to her namesake in Memphis. Estelle was too ill even to see the baby, but Faulkner wanted her and their daughter at home as soon as possible. There was no incubator at the hospital, and with a trained nurse for Alabama and practical nurse for Estelle, he thought they would do just as well at Rowan Oak. John Culley was a good-looking, dogmatic man whom Faulkner did not particularly like, but he was a fine doctor and his wife, Nina, was one of Estelle's best friends. He came every day because there were problems with the baby's digestive system. At the end of the week he could see that Alabama's condition was worsening. Faulkner and Dean [William's brother] went to Memphis for an incubator, but it was too late. On Tuesday afternoon, January 20, the baby died. Estelle had never seen her.

The family drove in three cars to St. Peter's Cemetery, and in the cold January morning Murry Falkner [William's father] prayed over the small grave. He was usually abrupt and inarticulate, but Sallie Murry remembered that now he offered a beautiful prayer. That afternoon the nurse brought Estelle a sedative. Then Bill came in and sat beside the bed. He told her about Alabama and wept—the first time she had ever seen him cry. She told him they would have another child.

"Bill," she said, "get you a drink."

"No," he said. "This is one time I'm not going to do it." Later Mr. Murry [Faulkner's father] came to see her. The baby had looked like Billy, he said. Billy had held the casket on his lap all the way to the cemetery.

As he had promised, Faulkner did not turn to liquor, not immediately. But there was one curious aftermath: it was a persistent rumor in Oxford that Faulkner had shot Dr. Culley in the shoulder. Estelle thought that Dr. Culley was in no way culpable in Alabama's death, but Faulkner apparently brooded over the lack of an incubator and felt that the child should have had better care. The rumor persisted in various forms. Faulkner had not shot Dr. Culley, but apparently he had wanted to. The rumor had originated with him. One symbolic response was more positive. Not long afterward he made the donation of an incubator—to Dr. Bramlett's hospital, to be used free of charge when parents could not pay for it.

His grief would remain acute for that whole year. …"

Excerpt taken from pp. 77-79 of Chapter 6 (entitled 'Two Brothers') of "Every Day by the Sun: A Memoir of the Faulkners of Mississippi," ©2011 Dean Faulkner Wells:

"When William purchased "the old Bailey place" on Garfield Avenue (now Old Taylor Road), he named the antebellum house and its thirteen acres "Rowan Oak." It was his way of declaring 'This is my private place'. To keep up payment and buy materials for repairs, he churned out stories at a furious pace, submitting thirty-seven in one year, but selling only six.

In midsummer of 1930, the 'Saturday Evening Post' accepted "Red Leaves," a short story whose subject differed from his other Yoknapatawpha sagas. It dealt with the Chickasaw Indians' tribal custom of burying their chiefs with their dogs, horses, and a slave—in this case a body servant not ready to die. The 'Post' paid him $750. Rowan Oak could now have electricity and Estelle a new stove.

Times were not easy for the newlyweds. William could not afford to hire carpenters to repair Rowan Oak, so Dean regularly brought fraternity brothers to help work on the house. They put on a new roof, rewired and expanded electrical circuits, and, thanks to "Red Leaves," put in new fixtures, ceiling lamps, pipes, and plumbing.

In spite of their financial difficulties, Estelle and William were eagerly looking forward to the birth of their first child in March 1931. So were Cho Cho and Malcolm [Estelle's children from her prior/first marriage].

Estelle's doctor, John Culley, was an excellent physician but a man with whom William did not get along. His wife, Nina, was Estelle's best friend. Dr. Culley was extremely concerned about Estelle because of the difficult deliveries of both of her children. In addition, she was weakened by anemia and weighed less than one hundred pounds. He warned her to be careful and prescribed iron and calcium pills for her.

Christmas at Rowan Oak with both their families in attendance was happy but exhausting for Estelle. She woke William late at night on January 10 and told him the baby was coming. At first he did not believe her, but he called Dr. Culley and asked him to meet them at the hospital. She gave birth the next day to a small, perfectly formed baby girl. They named her Alabama in honor of William's Aunt Bama. He wanted his wife and child at home, believing that since there was no incubator at Dr. Culley's hospital, they would be cared for just as well at Rowan Oak with a trained nurse for Alabama and a practical nurse for Estelle, who was too sick to care for the infant. Dr. Culley noticed that the baby had problems with her digestive tract. By the end of the week, this dilemma became life threatening. She was tiny and weak and could not retain any milk.

William was frantic. He tried everything, first hiring a wet nurse, then begging Dean to find a goat. Maybe the baby could digest goat milk. Within hours Dean brought one to Rowan Oak. The brothers took turns milking it and carrying the precious milk to the house. Nothing had prepared William for this terrible, grinding fear. The practical nurse tried to feed the milk to Alabama; then William tried, then Dean. She could not keep it down.

Dr. Culley suggested an incubator and William, desperate to get his hands on one but not trusting himself to drive, asked Dean to take him to Memphis. They drove in the middle of the road at top speed, passing every vehicle. They got an incubator and brought it back to Oxford—only to find the infant fading before their eyes. Dean sat up with William and Estelle all night. The next day, January 20, Alabama died. The Faulkners mourned as one. A private service was held at Rowan Oak and William read from the Bible. Dean drove to the cemetery while his brother cradled the tiny casket in his lap and wept. The rest of the family followed in two cars. It was bitter cold. At the gravesite, as his only granddaughter was laid to rest, Murry said a prayer that has been described as eloquent. William's grief staggered him. Soon after Alabama's death he donated an incubator to a second hospital in Oxford to be used free of charge by anyone in need."

Immediate Family & Household Relations-

William Faulkner (father) / Memorial #326

Estelle Oldham-Faulkner (mother) / 13603052

Malcolm Franklin (½ brother) / 13603167

Victoria "Cho Cho" Franklin (½ sister) / ???

Jill Faulkner-Summers (sister) / 57457345

Murry Falkner (gr father) / 35363577

Maud Butler-Faulkner (gr mother) / 35363614

Dean Swift Falkner (uncle) / 35363765

Dean Faulkner-Wells (first cousin) / 74049021

Caroline "Callie" Barr-Clark

(family servant) / 69850973