On Canyon Creek, Neal claimed property several miles south of the gold fields, but he prospected all over the area, possibly having a cabin on Pass Creek near the future site of Long Creek before settling on his land close to Canyon City. His Canyon City cabin was about six miles up Canyon Creek from town, and I believe he eventually had a home on Rebel Hill as well.

Neal knew and disliked famed frontier poet, Joaquin Miller, who resided in Canyon City from time to time. Miller was a literary hero to the school kids of the town, but Neal thought he was a total fraud. According to Neal, Miller's native wife was the only real talent/brains in the family.

The Halls lived next door to Thomas and Cora Sewell, the only black family in Grant County. Any blacks who drifted through Canyon City ended up at the Sewells' place first, and then typically found work at Neal's place. Thomas had a hauling business and didn't need help, but Neal had hundreds of head of cattle and horses and always needed ranch hands, and he preferred to hire African Americans. He was a strong believer in the equality of the races, and social justice for native Americans, black Americans, and Chinese Americans was a "thing" with him.

The grandson of former slaves, Sam McDonald, lived with the Halls and worked for Neal for about 5 months in 1899. About 55 years later, after an illustrious career at Stanford University, McDonald recalled the following in his autobiography (Sam McDonald's Farm, Stanford University Press, 1954):

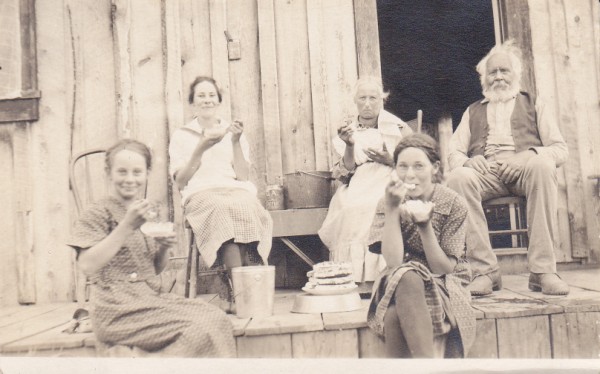

"Mr. Aaron Cornelius Hall . . . had many acres and raised horses and cattle. I collected part of my wages at seventy-five cents per day in cash, and applied the other part at one dollar per day toward the purchase of two horses. These cost twenty-five dollars apiece and were to be used for my return trip to California. The Halls were wonderful people . . . In my short employment they came to think of me as part of the family, and Mr. Hall promised me my pick of one of his three hundred head of range horses should I return to them again. My pack was sufficiently laden with food by Mrs. Hall to supply my needs for several days of my journey. At a breakfast unsurpassed on any table in those parts, sadness came over me when all gathered to wish me farewell. And so at last on October 11, 1900, I was off to begin my journey [back to California] . . . I started from Canyon City with three horses, the one for which I had traded my bicycle and the two which I had purchased with my labor."

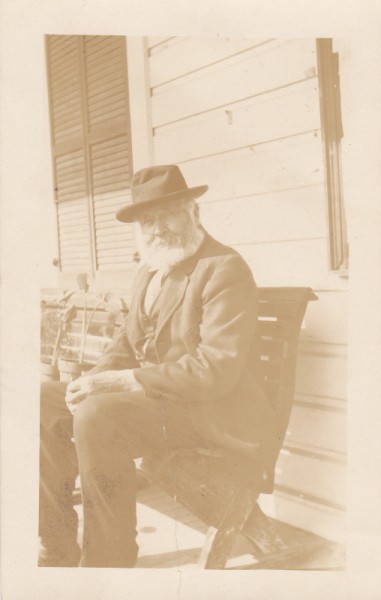

Neal took his own life on December 5, 1919, in the shed/garage of his old friend and fellow Canyon City pioneer, Oliver Perry Cresap. Neal left no note, but he had been despondent for almost two years about the death of his beloved son, William, who died at Walter Reed Hospital in Washington D.C. in March, 1918, less than a year after joining the army. Though William had kept the surname he was given at birth (he got the surname of his mother's husband at the time), he should have been a Hall because Neal was his biological father. Mary's husband drove her and infant William out of his house, and Neal took them in (including two other of Mary's Baier children). Neal and Mary married in 1899 when Neal was 61 years old! Neal loved William with all his heart, and it was despondency about William's death that drove him to take his own life.

On Canyon Creek, Neal claimed property several miles south of the gold fields, but he prospected all over the area, possibly having a cabin on Pass Creek near the future site of Long Creek before settling on his land close to Canyon City. His Canyon City cabin was about six miles up Canyon Creek from town, and I believe he eventually had a home on Rebel Hill as well.

Neal knew and disliked famed frontier poet, Joaquin Miller, who resided in Canyon City from time to time. Miller was a literary hero to the school kids of the town, but Neal thought he was a total fraud. According to Neal, Miller's native wife was the only real talent/brains in the family.

The Halls lived next door to Thomas and Cora Sewell, the only black family in Grant County. Any blacks who drifted through Canyon City ended up at the Sewells' place first, and then typically found work at Neal's place. Thomas had a hauling business and didn't need help, but Neal had hundreds of head of cattle and horses and always needed ranch hands, and he preferred to hire African Americans. He was a strong believer in the equality of the races, and social justice for native Americans, black Americans, and Chinese Americans was a "thing" with him.

The grandson of former slaves, Sam McDonald, lived with the Halls and worked for Neal for about 5 months in 1899. About 55 years later, after an illustrious career at Stanford University, McDonald recalled the following in his autobiography (Sam McDonald's Farm, Stanford University Press, 1954):

"Mr. Aaron Cornelius Hall . . . had many acres and raised horses and cattle. I collected part of my wages at seventy-five cents per day in cash, and applied the other part at one dollar per day toward the purchase of two horses. These cost twenty-five dollars apiece and were to be used for my return trip to California. The Halls were wonderful people . . . In my short employment they came to think of me as part of the family, and Mr. Hall promised me my pick of one of his three hundred head of range horses should I return to them again. My pack was sufficiently laden with food by Mrs. Hall to supply my needs for several days of my journey. At a breakfast unsurpassed on any table in those parts, sadness came over me when all gathered to wish me farewell. And so at last on October 11, 1900, I was off to begin my journey [back to California] . . . I started from Canyon City with three horses, the one for which I had traded my bicycle and the two which I had purchased with my labor."

Neal took his own life on December 5, 1919, in the shed/garage of his old friend and fellow Canyon City pioneer, Oliver Perry Cresap. Neal left no note, but he had been despondent for almost two years about the death of his beloved son, William, who died at Walter Reed Hospital in Washington D.C. in March, 1918, less than a year after joining the army. Though William had kept the surname he was given at birth (he got the surname of his mother's husband at the time), he should have been a Hall because Neal was his biological father. Mary's husband drove her and infant William out of his house, and Neal took them in (including two other of Mary's Baier children). Neal and Mary married in 1899 when Neal was 61 years old! Neal loved William with all his heart, and it was despondency about William's death that drove him to take his own life.

Gravesite Details

Buried in a row along with his wife, Mary, son Rollie, and step-children Frank, Katherine, and William.