On September 3, 1861, Moore enlisted at Frederick, Maryland as a private in Company B, 1st Potomac Home Brigade Cavalry (later part of Cole's 1st Maryland Volunteer Cavalry). Upon entering the service, James brought his own horse and was in turn paid for the "service" of the horse while with the cavalry. James was listed at enlistment as being age 20, 5'8", with ruddy complexion and light red hair. By occupation James was listed as a farmer.

James became ill in the winter, probably from exposure to the elements and was listed as sick in quarters on December 31, 1861. Apparently his sick furlough expired in January of 1862, as he was listed as being absent without leave for three (3) days on the Jan-Feb 1862 muster rolls. He was AWOL again for two (2) days on the March-April 1862 rolls; AWOL four (4) days, May-June 1862; AWOL for three (3) days Nov-Dec 1862; AWOL for one (1) day Jan-Feb 1863.

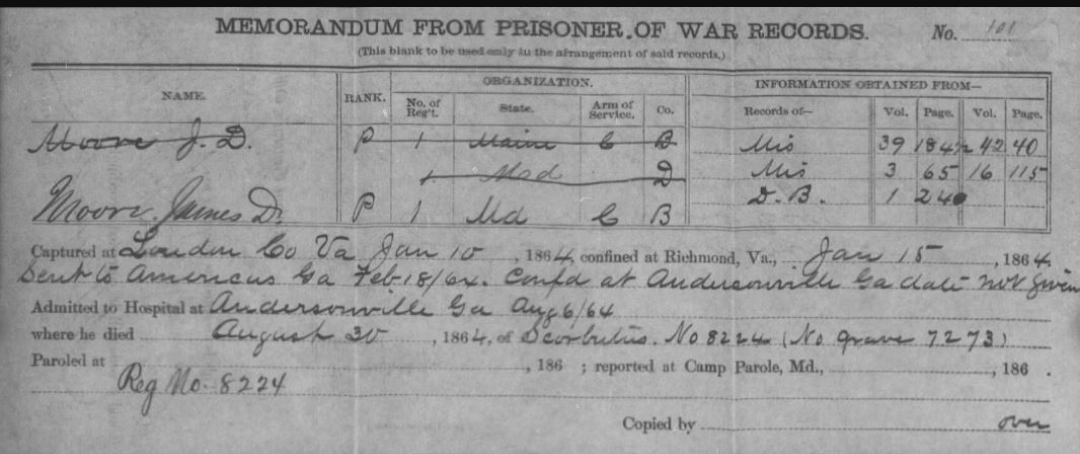

The events that led to Moore's trip to Andersonville began on January 10, 1864. Just before dawn on that freezing morning, Lt. Col. John Singleton Mosby and his raiders struck Cole's Battalion on Loudoun Heights. Moore was apparently captured in camp.

"For nine days we were lying in camp undisturbed, and almost fancied that all danger had passed, when suddenly, at 4 o'clock on the morning of the 10th of January, Moseby [sic] with his demons came yelling into camp. It was a moment never to be forgotten in a lifetime. They were firing into our tents, and three of them, my own among the number received seventy-seven balls into them. We were cut off from the officers, we could hear no word of command and we were so panic stricken that we did not know what to do. A number had already been killed and wounded, most of them in their tents. At length one of the boys cried out at the top of his voice, "boys, get out of your tents, lay down on the ground, and shoot every man on horseback." Taking my carbine in one hand, with my revolver in the other, I broke through their lines, as did many others. The men were dressed only in their night clothes, and many of them barefooted running over the frozen ground, opened up such a fire upon them, as to cause them to retire, but not without taking from us a number of horses, and a few prisoners. One young man, a friend of mine, by the name of James Moore, while in the tent dropped his carbine, and lay down, saying, 'O my God.' Whether he was wounded or not, I do not know, for he was carried away, and I believe never heard from." - "Three-Years Around the camp-Fires in Virginia", by Jacob F. Breish (also of Co. B, Cole's Cavalry).

By the time that Mosby had decided to withdraw, he had suffered severe losses, including the wounding of his younger brother "Willie". In addition to the six captured Federal troopers, Cole's battalion had lost seven killed and fourteen wounded (a review of service records indicates actual numbers killed and wounded at four and ten, respectively. One of those wounded received a mortal wound). However, the men lost from Mosby's command were deemed by one ranger as "worth more than all Cole's Battalion." Considering all of this, a truce was made later that morning and Captain William Henry Chapman dispatched a messenger into the Federal camp with an offer for an exchange. For the recovery of his men, Mosby would return the six captured Federal troopers. Cole refused to receive the offer, ultimately sealing Moore's fate.

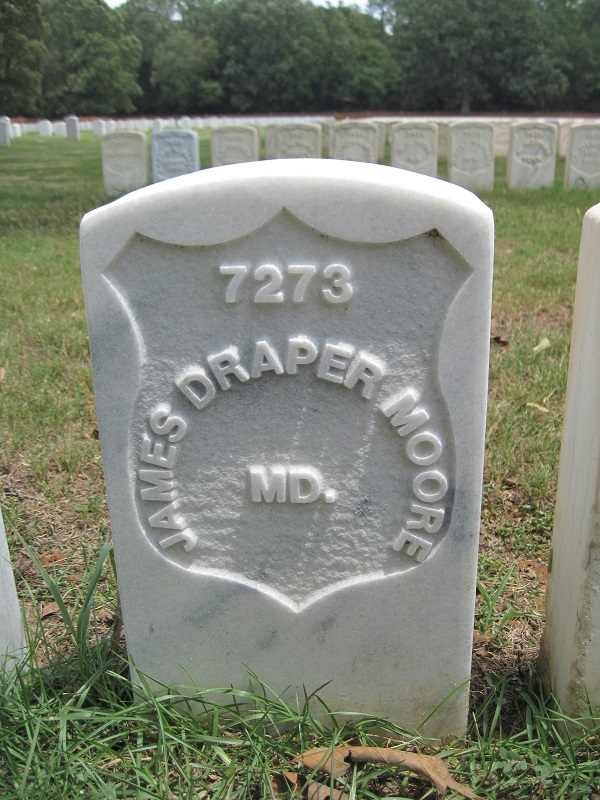

First sent to Belle Island, Richmond, Va., James was shortly after transferred to Andersonville Prison, Ga. On August 30, 1864 (only seven days after what was considered the worst day in Andersonville's history for deaths), when the prison camp was at its peak for disease and deaths due to overcrowding, James died of scobitis (scurvy). He is in grave #7273 at Andersonville.

After the war both of his James D. Moore's parents applied for and received a pension for his service. James' mother's application was dated 7/26/1880; father's 5/23/1888. Both records of this pension and military service are on file at the National Archives in Washington, D.C.

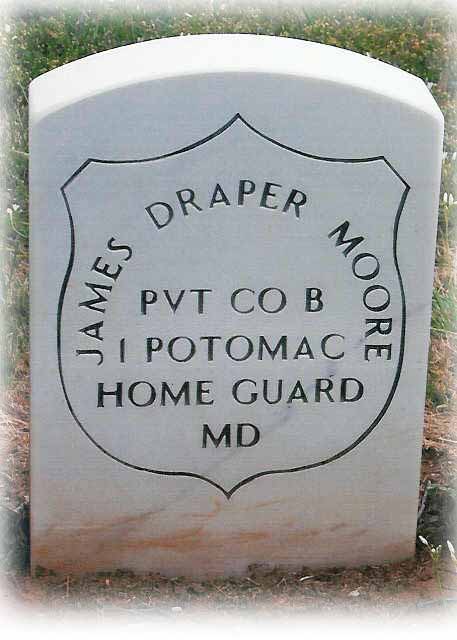

Upon a tour to Camp Sumter (Andersonville) in mid-April 1997, I found that the grave of J.D. Moore was mismarked. At that time, grave #7273 showed a "M.L. Moore" from Maine. Thankfully, Atwater's book of 1866 provides reliable information, listing Moore. It seems likely that several may be misidentified in later years when the headstones replaced the older markers. By the spring of 1998, Andersonville, after my submission of various documents to prove that J.D. Moore was in that grave, erected a headstone that properly described his resting place. In 2011, the stone (and many others in the cemetery) was replaced by the site, to match earlier stones, in appearance (see the first photo at top of page, showing stone with raised lettering).

Comrades of James Moore also captured at Loudoun Heights included...

Hamilton Wolf, (died Nov. 24 (grave #12147); mother applied for and received a pension)

George Weaver, (died Sept. 21 of diarrhea (grave #9409); in 1884, his father applied for a pension for his son's service)

Isaiah Nicewander, Died at Richmond, of typhoid, 4/6/64. (mother applied for but did not receive a pension)

John Newcomber (died August 6, of diarrhea (grave #4881); in 1865, his wife applied for, and received, a pension based on his service. A minor also applied at a later time and received a pension)

Walter Scott Myers (died May 23, 1864 of chronic diarrhea (grave #1307); mother applied for and received a pension)

Another comrade (Abraham L. Sossey) from the same company, who was killed in the fight at Loudoun Heights, is buried in the same cemetery as James D. Moore's parents.

On September 3, 1861, Moore enlisted at Frederick, Maryland as a private in Company B, 1st Potomac Home Brigade Cavalry (later part of Cole's 1st Maryland Volunteer Cavalry). Upon entering the service, James brought his own horse and was in turn paid for the "service" of the horse while with the cavalry. James was listed at enlistment as being age 20, 5'8", with ruddy complexion and light red hair. By occupation James was listed as a farmer.

James became ill in the winter, probably from exposure to the elements and was listed as sick in quarters on December 31, 1861. Apparently his sick furlough expired in January of 1862, as he was listed as being absent without leave for three (3) days on the Jan-Feb 1862 muster rolls. He was AWOL again for two (2) days on the March-April 1862 rolls; AWOL four (4) days, May-June 1862; AWOL for three (3) days Nov-Dec 1862; AWOL for one (1) day Jan-Feb 1863.

The events that led to Moore's trip to Andersonville began on January 10, 1864. Just before dawn on that freezing morning, Lt. Col. John Singleton Mosby and his raiders struck Cole's Battalion on Loudoun Heights. Moore was apparently captured in camp.

"For nine days we were lying in camp undisturbed, and almost fancied that all danger had passed, when suddenly, at 4 o'clock on the morning of the 10th of January, Moseby [sic] with his demons came yelling into camp. It was a moment never to be forgotten in a lifetime. They were firing into our tents, and three of them, my own among the number received seventy-seven balls into them. We were cut off from the officers, we could hear no word of command and we were so panic stricken that we did not know what to do. A number had already been killed and wounded, most of them in their tents. At length one of the boys cried out at the top of his voice, "boys, get out of your tents, lay down on the ground, and shoot every man on horseback." Taking my carbine in one hand, with my revolver in the other, I broke through their lines, as did many others. The men were dressed only in their night clothes, and many of them barefooted running over the frozen ground, opened up such a fire upon them, as to cause them to retire, but not without taking from us a number of horses, and a few prisoners. One young man, a friend of mine, by the name of James Moore, while in the tent dropped his carbine, and lay down, saying, 'O my God.' Whether he was wounded or not, I do not know, for he was carried away, and I believe never heard from." - "Three-Years Around the camp-Fires in Virginia", by Jacob F. Breish (also of Co. B, Cole's Cavalry).

By the time that Mosby had decided to withdraw, he had suffered severe losses, including the wounding of his younger brother "Willie". In addition to the six captured Federal troopers, Cole's battalion had lost seven killed and fourteen wounded (a review of service records indicates actual numbers killed and wounded at four and ten, respectively. One of those wounded received a mortal wound). However, the men lost from Mosby's command were deemed by one ranger as "worth more than all Cole's Battalion." Considering all of this, a truce was made later that morning and Captain William Henry Chapman dispatched a messenger into the Federal camp with an offer for an exchange. For the recovery of his men, Mosby would return the six captured Federal troopers. Cole refused to receive the offer, ultimately sealing Moore's fate.

First sent to Belle Island, Richmond, Va., James was shortly after transferred to Andersonville Prison, Ga. On August 30, 1864 (only seven days after what was considered the worst day in Andersonville's history for deaths), when the prison camp was at its peak for disease and deaths due to overcrowding, James died of scobitis (scurvy). He is in grave #7273 at Andersonville.

After the war both of his James D. Moore's parents applied for and received a pension for his service. James' mother's application was dated 7/26/1880; father's 5/23/1888. Both records of this pension and military service are on file at the National Archives in Washington, D.C.

Upon a tour to Camp Sumter (Andersonville) in mid-April 1997, I found that the grave of J.D. Moore was mismarked. At that time, grave #7273 showed a "M.L. Moore" from Maine. Thankfully, Atwater's book of 1866 provides reliable information, listing Moore. It seems likely that several may be misidentified in later years when the headstones replaced the older markers. By the spring of 1998, Andersonville, after my submission of various documents to prove that J.D. Moore was in that grave, erected a headstone that properly described his resting place. In 2011, the stone (and many others in the cemetery) was replaced by the site, to match earlier stones, in appearance (see the first photo at top of page, showing stone with raised lettering).

Comrades of James Moore also captured at Loudoun Heights included...

Hamilton Wolf, (died Nov. 24 (grave #12147); mother applied for and received a pension)

George Weaver, (died Sept. 21 of diarrhea (grave #9409); in 1884, his father applied for a pension for his son's service)

Isaiah Nicewander, Died at Richmond, of typhoid, 4/6/64. (mother applied for but did not receive a pension)

John Newcomber (died August 6, of diarrhea (grave #4881); in 1865, his wife applied for, and received, a pension based on his service. A minor also applied at a later time and received a pension)

Walter Scott Myers (died May 23, 1864 of chronic diarrhea (grave #1307); mother applied for and received a pension)

Another comrade (Abraham L. Sossey) from the same company, who was killed in the fight at Loudoun Heights, is buried in the same cemetery as James D. Moore's parents.

Family Members

Advertisement

Explore more

Sponsored by Ancestry

Advertisement