"The LaFayette Clipper" - LaFayette, Chambers County, Alabama, Thursday, January 3, 1878:

"The People, their voice shall be heard and their rights vindicated"

$200 Reward!!

A Proclamation by the Governor.

State of Alabama, Executive Department

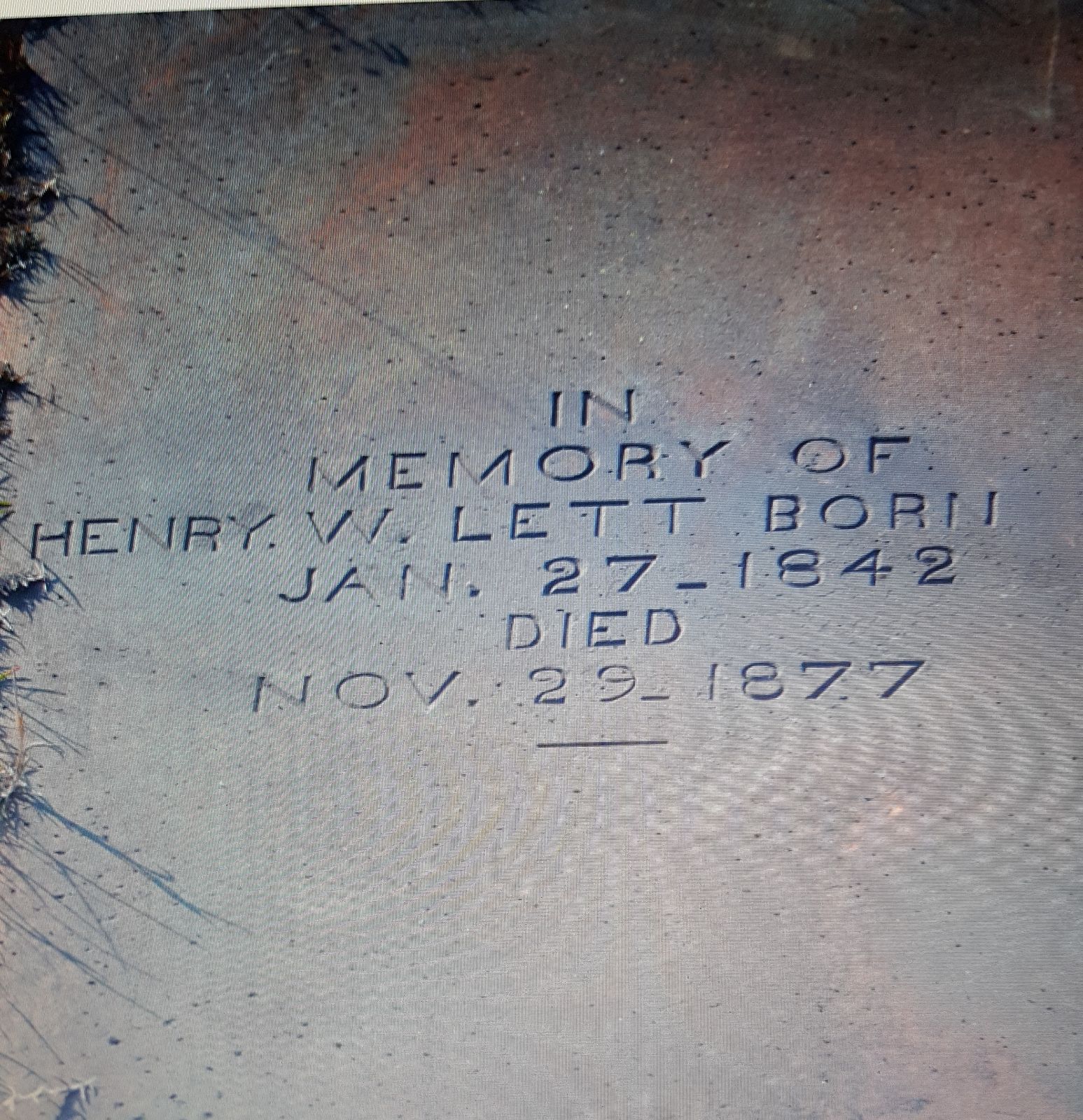

Whereas, authentic information has reached this Department, that on the 29th, day of November 1877, in the County of Chambers, in said State, Henry Lett was murdered, and whereas it is formerly charged that one Zachaeus H. Kimbrough perpetrated said murder, and is now at large.

Now, therefore, I, Geo. S. Houston , by virtue of the power and authority in me vested, as Governor of Alabama do issue this my proclamation offering a reward of two hundred ($200) dollars for the arrest and delivery of the said Zacheus H. Kimbrough to the Sheriff of Chambers County, Alabama. The reward to be paid to the person, or persons, that the said Sheriff may certify to be entitled thereto.

Given under my hand, and the Great Seal of State, this the 13th day of December, A. D., 1877, and of the Independence of the United States of America the 102nd year.

Geo. S. Houston

By the Governor, Rufus K. Boyd , Secretary of State

Description - The said Kimbrough is about 22 years old, about 5 feet 8 or 10 inches high, hair is of dark auburn and inclined to curl, high forehead, rather high cheek bone, chin sharp, shows his teeth in talking, slow spoken, has Roman nose, broad shoulders, narrow hips and drops his shoulders in walking, beard red, has downcast countenance and will weigh about 145 or 150 pounds.

==========

The following is more information from the Court Case:

248 SUPREME COURT December Term,

[Kimbrough v. The State.]

Indictment for Murder.

1. Jury ; what properly organized.— The fact that one or more of the persons

on the venue served on a prisoner, charged with a capital offense, were on the

regular juries for the week, and could not be obtained as jurors for the pris-

oner's trial, because then engaged on the trial of another cause, gives the

prisoner no right to delay the impanneling of the jury for his own trial, until

such persons are discharged as jurors on the other case, or to otherwise delay

the trial.

2. Killing ; what cannot he set up to excuse.— A slayer cannot urge, in his own

justification, a necessity produced by his own wrongful and unlawful act, as a

valid reason for killing his assailant.

Appeal from Chambers Circuit Court.

Tried before Hon. James E. Cobb.

The appellant was indicted for the murder of one Henry

Lett, and the list of jurors for his trial, which was duly

served on him, contained the regular jurors for the week.

In drawing the jury for his trial, the third name and others

were those on a regular jury then engaged in the trial of

another cause. The judge ordered the names of these

jurors, as they were drawn, laid aside, and that others be

drawn in their stead. The defendant objected, and insisted

that they should be called from the jury room and put upon

the parties for acceptance or rejection, which the court

refused to do, and defendant excepted. The list served

upon the prisoner having been exhausted before a jury for

his trial was obtained, and those on the list which were in

the jury room not having returned, it was ordered that an

additional number be summoned, according to the statute,

to complete the jury. To this action the defendant duly

excepted.

There was evidence, in this cause, from two witnesses who

were present at the killing, to the effect that they were

attracted by loud talking, and, on going to the place whence

it proceeded, found the deceased and defendant engaged in

a controversy about a note. One of these witnesses testified

that soon afterward the deceased, in turning or stepping

backward, struck his feet against some obstacle, and fell to

the ground. When the deceased fell, the defendant rushed

upon him, and cut him in the neck with a knife. There was

evidence tending to show that this witness had made state-

VOL. T.Ttn.

1878.1 OF ALABAMA. 249

[Kimbrough v. The State,]

ments to the effect that the deceased was stooping to pick

up a rock when the defendant cut him.

Another witness for the State, who was a brother of

deceased, testified that the defendant, with his left hand

against the shoulder and his knee against the thigh of

deceased, pushed him backward, when the foot of deceased

striking some object, he fell, and, as he was falling, the

defendant struck him with a knife in the neck ; that witness

attempted to arrest the defendant, after the cutting, but

defendant cut witness with the knife and ran ; that witness

followed the defendant a short distance, and threw a rock at

him, and returned to his brother, who died almost imme-

diately.

One Joe Smith, a witness for the defendant, testified that

he was passing along the road near where the deceased and

defendant were standing, some fifteen steps from them ; that

he heard them quarreling, and heard the deceased say to the

defendant, "put up your knife, and fight a fair fight," and

heard the defendant say, in reply, "that he would not do it;

that his finger was sore, and he could not fight."

After the general charge had been given, the counsel for

the defense orally asked the court to instruct the jury, as

part of the law of self defense, "that the law does not

require a party to retreat before taking life, if by so doing

he increases his peril." This charge, the court refused to

give; but, instead, instructed the jury that if a person

willingly engage in a fight, and, in the fight so willingly

engaged in by him, kills his opponent, he cannot invoke the

doctrine of self defense to his entire justification — unless it

appears that he had done all he could reasonably do to

avoid the combat, even to a retreat, though, by so doing, he

increased his peril. To this charge, the defendant excepted.

The jury found the defendant guilty of murder in the

second degree, and assessed his punishment at forty years'

imprisonment in the penitentiary; and judgment was rendered accordingly.

No counsel for appellant.

Henry C. Tompkins, Attorney-General, contra.

MANNING, J. — Appellant was charged with the murder

of one Henry Lett, and among the persons of the venue

summoned to compose a jury to try him, of which a list had

been duly served, were, as the statute directs, those who

belonged to the regular juries of the week ; and, in drawing

out the names, the third and others were some of these, who

250 SUPREME COURT IDec Term,

[Kimbrough v. The State.]

were then in a room in the court-house engaged, as members

of a jury, in the consideration of another criminal case,

which had been committed to them, under their oath, to

render a true verdict therein. The Judge, therefore, ordered

their names, as they were respectively drawn, laid aside, and

that others be drawn in their stead. To this course, the

defendant objected, and insisted that they should be called

from the jury room as their names were drawn, and put

upon the parties for acceptance or rejection ; which being

refused, defendant excepted. And the names of all who

were originally summoned having been exhausted before the

jury was complete, and those who were in the jury room not

having yet returned, it was ordered that an additional num-

ber be summoned from the bystanders, or others, according

to the statute, for the completion of the jury ; to which, also,

defendant duly reserved an exception. And it is insisted

that tlie objection of defendant should have been allowed,

and the business of the court suspended until the jury then

out returned into court, and were discharged of the case

committed to them.

The constitution gives to the person indicted the right to

a trial "by an impartial jury." How this shall be consti-

tuted, it is left to the legislature to provide. To this end, it

was enacted, among other things, that for the trial of a cap-

ital case, there shall be summoned to select from "not less

than fifty nor more than one hundred persons, including

those summoned on the regular juries for the week." — Code

of 1876, § 4874. A list of these is to be delivered to de-

fendant, if he is in confinement, one entire day before the

trial. — § 4872. If the persons summoned as jurors fail to

appear, or if the panel is exhausted by challenges, neither

the defendant nor his counsel is entitled to a list of the per-

sons summoned to supply their places." — § 4873. "A mis-

take in the name of any person summoned as a juror for the

trial of a capital offense, either in the venire, or in the list of

jurors delivered to the defendant, is not sufficient to quash

the venire, or to delay or continue the trial, unless the court, in

its discretion, is of the opinion that the ends of justice so

require. Others are to be " forthwith summoned to supply

their places."— § 4876. And " any person who appears to

the court to be unfit to serve on the jury, may be excused

on his own motion, or at the instance of either party." —

§ 4885. If all the slips of paper containing the names of

those first summoned are drawn, "and the jury is not made

up,^ the court must direct the sheriff to summon at least

twice the number of jurors required to complete the jury,

Vol. LXN.

1878.] OF ALABAMA. 251

[Kimbrough v. The State.]

whose names are also to be written on slips of paper, de-

posited and drawn." — § 4878.

These enactments manifest a desire to favor the accused

in the circumstances provided for, so far as the due admin-

istration of the law will permit, but not to such an extent as

" to delay or continue the trial," or obstruct the business of

the court. It is presumable that when the legislature

authorized the summoning of " the regular jurors in at-

tendance " among the number, not less than fifty nor more

than one hundred, above mentioned, it contemplated that

some of those regular jurors might, at some time when their

names were called, be engaged in the trial or consideration

of another cause, from which they could not, without a vio-

lation of law and of the rights of other parties, be dis-

charged or brought into court, or voluntarily come them-

selves.— 1 Bish. Cr. Pr. § S95. See, also, Clark's Man. of

Cr. Law, pp. 450-5L Being thus kept away, the contin-

gency has happened, when other persons should be sum-

moned to supply their places.

Any other construction than this of the statutes would

often produce the stoppage, in such conjunctures, of all the

important remaining business of the court. For, if it must

idly wait until the jury out shall agree on a verdict and

bring it in, the term during which the court may lawfully

remain in session might expire, or so much of it be wasted

that other causes could not be tried, and those interested

in them, perhaps innocent persons impatient for a trial, be

consequently kept in prison six months longer, until the

court shall again be holden. Consequences so oppressive

could not have been intended by the legislature; and its

enactments should not be so construed as to produce them.

It is a case in which the maxim, augumentum ab inconvenieniti

plurimum valet, is applicable. — 11 Meeson & W. 928-9 ;

10 id. 434.

The judge did not err in ordering the drawing for jurors

to proceed.

Nor was there any error in the refusal to charge, in this

case, as requested, or in the charge given which was ex-

cepted to.

A slayer cannot urge, in justification, a necessity produced

by his own unlawful and wrongful act, as a valid reason why

he may lawfully kill his adversarv. — Eiland v. State. 52 Ala.

332 ; Leivis v. State, 51 Ala. 1 ; Clark's Man. of Cr. Law,

§ 377 et seq., and cases there cited.

Let the judgment of the circuit court be affirmed.

==========

"The LaFayette Clipper" - LaFayette, Chambers County, Alabama, Thursday, January 3, 1878:

"The People, their voice shall be heard and their rights vindicated"

$200 Reward!!

A Proclamation by the Governor.

State of Alabama, Executive Department

Whereas, authentic information has reached this Department, that on the 29th, day of November 1877, in the County of Chambers, in said State, Henry Lett was murdered, and whereas it is formerly charged that one Zachaeus H. Kimbrough perpetrated said murder, and is now at large.

Now, therefore, I, Geo. S. Houston , by virtue of the power and authority in me vested, as Governor of Alabama do issue this my proclamation offering a reward of two hundred ($200) dollars for the arrest and delivery of the said Zacheus H. Kimbrough to the Sheriff of Chambers County, Alabama. The reward to be paid to the person, or persons, that the said Sheriff may certify to be entitled thereto.

Given under my hand, and the Great Seal of State, this the 13th day of December, A. D., 1877, and of the Independence of the United States of America the 102nd year.

Geo. S. Houston

By the Governor, Rufus K. Boyd , Secretary of State

Description - The said Kimbrough is about 22 years old, about 5 feet 8 or 10 inches high, hair is of dark auburn and inclined to curl, high forehead, rather high cheek bone, chin sharp, shows his teeth in talking, slow spoken, has Roman nose, broad shoulders, narrow hips and drops his shoulders in walking, beard red, has downcast countenance and will weigh about 145 or 150 pounds.

==========

The following is more information from the Court Case:

248 SUPREME COURT December Term,

[Kimbrough v. The State.]

Indictment for Murder.

1. Jury ; what properly organized.— The fact that one or more of the persons

on the venue served on a prisoner, charged with a capital offense, were on the

regular juries for the week, and could not be obtained as jurors for the pris-

oner's trial, because then engaged on the trial of another cause, gives the

prisoner no right to delay the impanneling of the jury for his own trial, until

such persons are discharged as jurors on the other case, or to otherwise delay

the trial.

2. Killing ; what cannot he set up to excuse.— A slayer cannot urge, in his own

justification, a necessity produced by his own wrongful and unlawful act, as a

valid reason for killing his assailant.

Appeal from Chambers Circuit Court.

Tried before Hon. James E. Cobb.

The appellant was indicted for the murder of one Henry

Lett, and the list of jurors for his trial, which was duly

served on him, contained the regular jurors for the week.

In drawing the jury for his trial, the third name and others

were those on a regular jury then engaged in the trial of

another cause. The judge ordered the names of these

jurors, as they were drawn, laid aside, and that others be

drawn in their stead. The defendant objected, and insisted

that they should be called from the jury room and put upon

the parties for acceptance or rejection, which the court

refused to do, and defendant excepted. The list served

upon the prisoner having been exhausted before a jury for

his trial was obtained, and those on the list which were in

the jury room not having returned, it was ordered that an

additional number be summoned, according to the statute,

to complete the jury. To this action the defendant duly

excepted.

There was evidence, in this cause, from two witnesses who

were present at the killing, to the effect that they were

attracted by loud talking, and, on going to the place whence

it proceeded, found the deceased and defendant engaged in

a controversy about a note. One of these witnesses testified

that soon afterward the deceased, in turning or stepping

backward, struck his feet against some obstacle, and fell to

the ground. When the deceased fell, the defendant rushed

upon him, and cut him in the neck with a knife. There was

evidence tending to show that this witness had made state-

VOL. T.Ttn.

1878.1 OF ALABAMA. 249

[Kimbrough v. The State,]

ments to the effect that the deceased was stooping to pick

up a rock when the defendant cut him.

Another witness for the State, who was a brother of

deceased, testified that the defendant, with his left hand

against the shoulder and his knee against the thigh of

deceased, pushed him backward, when the foot of deceased

striking some object, he fell, and, as he was falling, the

defendant struck him with a knife in the neck ; that witness

attempted to arrest the defendant, after the cutting, but

defendant cut witness with the knife and ran ; that witness

followed the defendant a short distance, and threw a rock at

him, and returned to his brother, who died almost imme-

diately.

One Joe Smith, a witness for the defendant, testified that

he was passing along the road near where the deceased and

defendant were standing, some fifteen steps from them ; that

he heard them quarreling, and heard the deceased say to the

defendant, "put up your knife, and fight a fair fight," and

heard the defendant say, in reply, "that he would not do it;

that his finger was sore, and he could not fight."

After the general charge had been given, the counsel for

the defense orally asked the court to instruct the jury, as

part of the law of self defense, "that the law does not

require a party to retreat before taking life, if by so doing

he increases his peril." This charge, the court refused to

give; but, instead, instructed the jury that if a person

willingly engage in a fight, and, in the fight so willingly

engaged in by him, kills his opponent, he cannot invoke the

doctrine of self defense to his entire justification — unless it

appears that he had done all he could reasonably do to

avoid the combat, even to a retreat, though, by so doing, he

increased his peril. To this charge, the defendant excepted.

The jury found the defendant guilty of murder in the

second degree, and assessed his punishment at forty years'

imprisonment in the penitentiary; and judgment was rendered accordingly.

No counsel for appellant.

Henry C. Tompkins, Attorney-General, contra.

MANNING, J. — Appellant was charged with the murder

of one Henry Lett, and among the persons of the venue

summoned to compose a jury to try him, of which a list had

been duly served, were, as the statute directs, those who

belonged to the regular juries of the week ; and, in drawing

out the names, the third and others were some of these, who

250 SUPREME COURT IDec Term,

[Kimbrough v. The State.]

were then in a room in the court-house engaged, as members

of a jury, in the consideration of another criminal case,

which had been committed to them, under their oath, to

render a true verdict therein. The Judge, therefore, ordered

their names, as they were respectively drawn, laid aside, and

that others be drawn in their stead. To this course, the

defendant objected, and insisted that they should be called

from the jury room as their names were drawn, and put

upon the parties for acceptance or rejection ; which being

refused, defendant excepted. And the names of all who

were originally summoned having been exhausted before the

jury was complete, and those who were in the jury room not

having yet returned, it was ordered that an additional num-

ber be summoned from the bystanders, or others, according

to the statute, for the completion of the jury ; to which, also,

defendant duly reserved an exception. And it is insisted

that tlie objection of defendant should have been allowed,

and the business of the court suspended until the jury then

out returned into court, and were discharged of the case

committed to them.

The constitution gives to the person indicted the right to

a trial "by an impartial jury." How this shall be consti-

tuted, it is left to the legislature to provide. To this end, it

was enacted, among other things, that for the trial of a cap-

ital case, there shall be summoned to select from "not less

than fifty nor more than one hundred persons, including

those summoned on the regular juries for the week." — Code

of 1876, § 4874. A list of these is to be delivered to de-

fendant, if he is in confinement, one entire day before the

trial. — § 4872. If the persons summoned as jurors fail to

appear, or if the panel is exhausted by challenges, neither

the defendant nor his counsel is entitled to a list of the per-

sons summoned to supply their places." — § 4873. "A mis-

take in the name of any person summoned as a juror for the

trial of a capital offense, either in the venire, or in the list of

jurors delivered to the defendant, is not sufficient to quash

the venire, or to delay or continue the trial, unless the court, in

its discretion, is of the opinion that the ends of justice so

require. Others are to be " forthwith summoned to supply

their places."— § 4876. And " any person who appears to

the court to be unfit to serve on the jury, may be excused

on his own motion, or at the instance of either party." —

§ 4885. If all the slips of paper containing the names of

those first summoned are drawn, "and the jury is not made

up,^ the court must direct the sheriff to summon at least

twice the number of jurors required to complete the jury,

Vol. LXN.

1878.] OF ALABAMA. 251

[Kimbrough v. The State.]

whose names are also to be written on slips of paper, de-

posited and drawn." — § 4878.

These enactments manifest a desire to favor the accused

in the circumstances provided for, so far as the due admin-

istration of the law will permit, but not to such an extent as

" to delay or continue the trial," or obstruct the business of

the court. It is presumable that when the legislature

authorized the summoning of " the regular jurors in at-

tendance " among the number, not less than fifty nor more

than one hundred, above mentioned, it contemplated that

some of those regular jurors might, at some time when their

names were called, be engaged in the trial or consideration

of another cause, from which they could not, without a vio-

lation of law and of the rights of other parties, be dis-

charged or brought into court, or voluntarily come them-

selves.— 1 Bish. Cr. Pr. § S95. See, also, Clark's Man. of

Cr. Law, pp. 450-5L Being thus kept away, the contin-

gency has happened, when other persons should be sum-

moned to supply their places.

Any other construction than this of the statutes would

often produce the stoppage, in such conjunctures, of all the

important remaining business of the court. For, if it must

idly wait until the jury out shall agree on a verdict and

bring it in, the term during which the court may lawfully

remain in session might expire, or so much of it be wasted

that other causes could not be tried, and those interested

in them, perhaps innocent persons impatient for a trial, be

consequently kept in prison six months longer, until the

court shall again be holden. Consequences so oppressive

could not have been intended by the legislature; and its

enactments should not be so construed as to produce them.

It is a case in which the maxim, augumentum ab inconvenieniti

plurimum valet, is applicable. — 11 Meeson & W. 928-9 ;

10 id. 434.

The judge did not err in ordering the drawing for jurors

to proceed.

Nor was there any error in the refusal to charge, in this

case, as requested, or in the charge given which was ex-

cepted to.

A slayer cannot urge, in justification, a necessity produced

by his own unlawful and wrongful act, as a valid reason why

he may lawfully kill his adversarv. — Eiland v. State. 52 Ala.

332 ; Leivis v. State, 51 Ala. 1 ; Clark's Man. of Cr. Law,

§ 377 et seq., and cases there cited.

Let the judgment of the circuit court be affirmed.

==========

Family Members

Advertisement

Advertisement