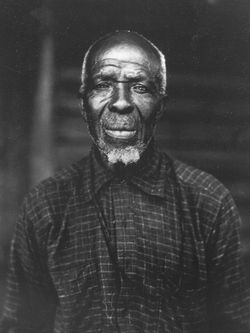

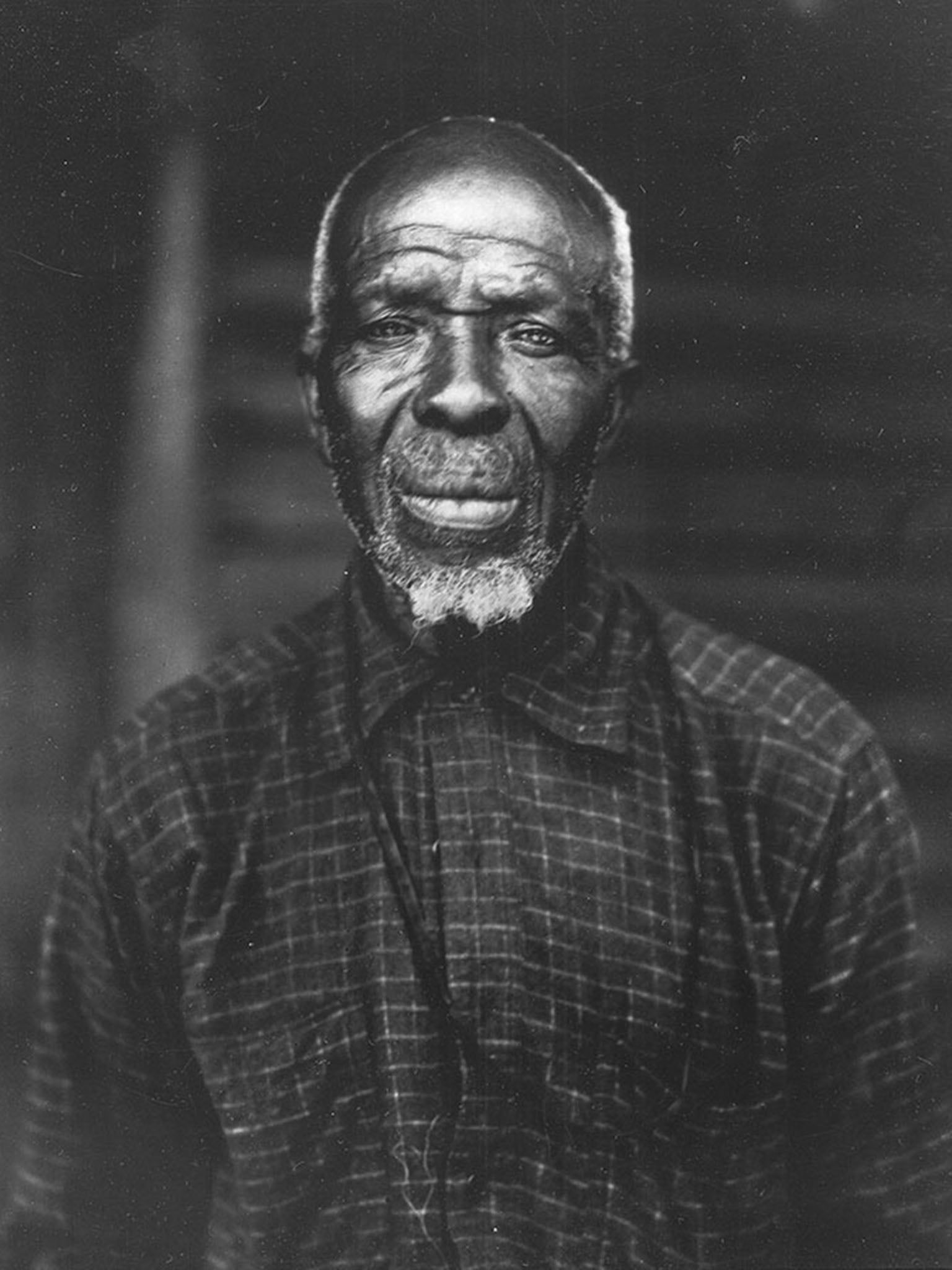

Mr. Lewis is both a significant and notable historical figure as an African brought to the United States in the final days of the slave trade, and one of the founders of Africa Town USA (known today as Africatown). This community of the last African slaves illegally brought to the US in 1860 is nationally recognized for its cultural and heritage significance and their contributions to the American story. According to the National Park Service National Register of Historic Places, Africatown was significant for this national heritage site designation as it "was the first settlement founded by Africans who built their very own town on their own land in the United States.". As an elder Mr. Lewis became a leader of this community that, following many struggles affecting such communities, is remembered and featured in a documentary produced by Netflix in 2022 titled "Descendant". The story of the Clorilda and its rediscovery in 2018 has brought global recognition to the efforts of Mr. Lewis, the survivors of this voyage and the community which they built.

The life of Cudjo Lewis is a complex story that reflects the social, cultural and political history of the time period. His life's story spans two continents. Centered around an illegal bet by two American businessmen a continent away from his home in Africa, he endures the hardship of captivity aboard the slave ship Clotilda, then according to accounts, the unfulfilled dream of returning to his homeland, and culminates in the founding and building of a community called Africa Town. Today the history is told by his descendants both in the US and in his homeland in West Africa.

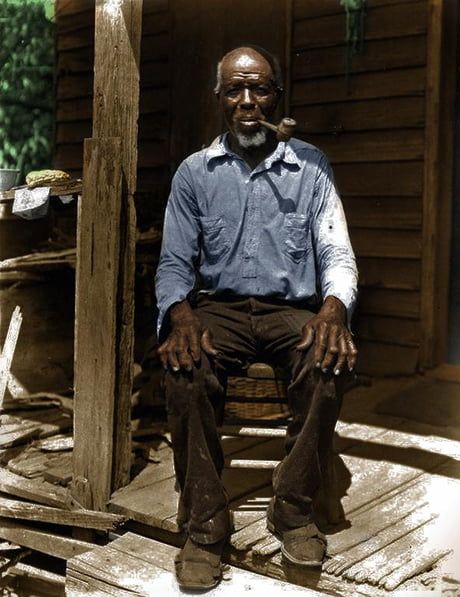

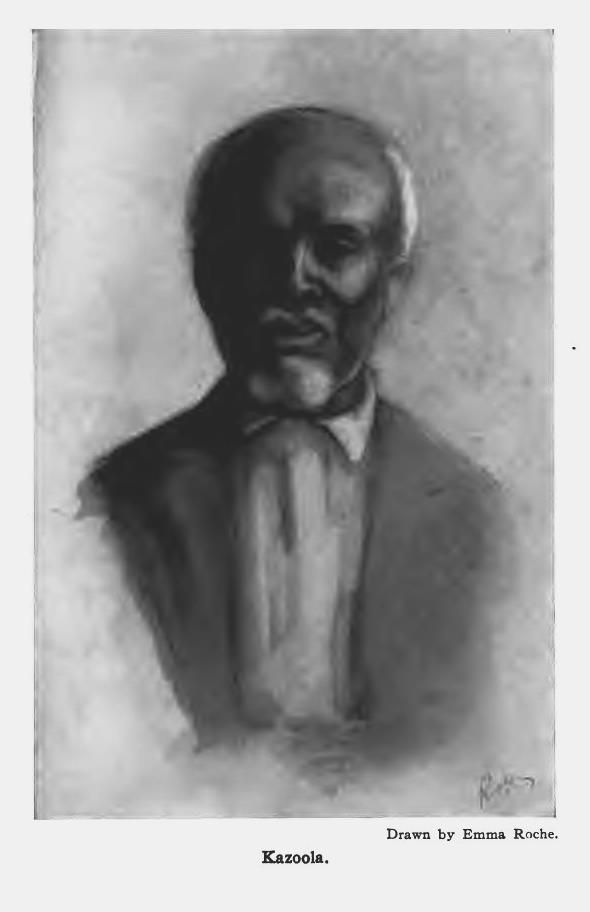

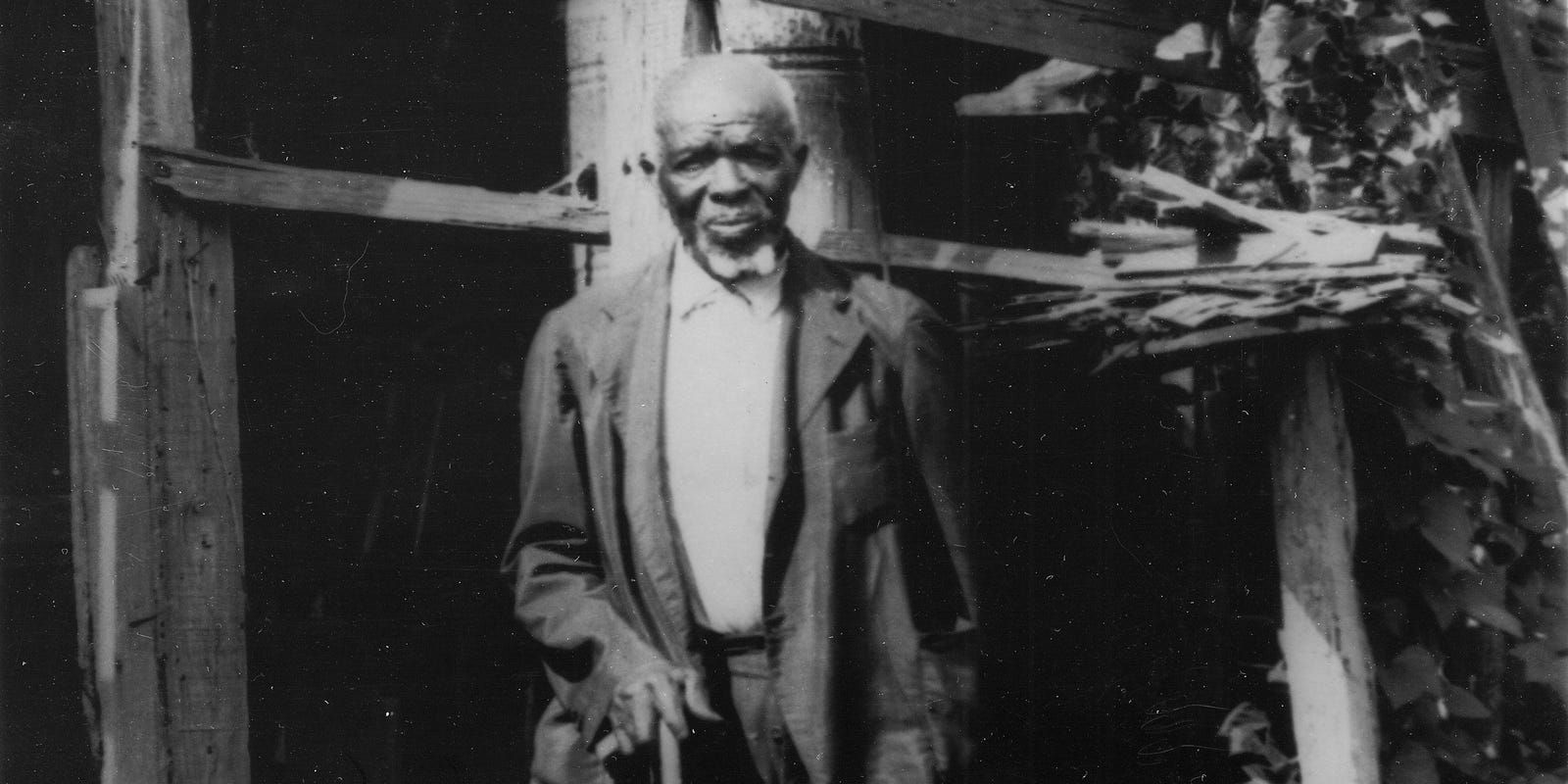

As told by the noted historian and author Zora Neale Hurston (in her 2018 book Barracoon,The Story Of The Last "Black Cargo''), Cudjo Lewis, or Oluale Kossola as he was known by his African name, was born around 1841 in Bante in West Africa to Oluale and Fondlolu. As noted in Hurston's interviews with Mr. Lewis, he trained as a soldier and by the age of fourteen, he became skilled in hunting and tracking and had acquired expertise in shooting arrows and throwing spears and had gained respect and recognition in his community.

Although a US law was passed in 1808 abolishing the trans-Atlantic slave trade, by all accounts the practice continued over the next fifty years. According to multiple sources the slave trade which was strong at the time in Africa resulted in raids of Cudjo's town of Bante. Cudjo, who was captured along with others in the community, was then taken to Ouidah known as the "Slave Coast" in West Africa in what is present day Benin. The captives were held in barracoons or barrack like structures while awaiting transportation across the Atlantic.

Reports on the activities that were taking place in this region reached the newspapers in Mobile, Alabama in November, 1858 and caught the attention of a wealthy local slave trader and plantation owner in Mobile, Alabama. In defiance of the law a bet was made that he could bring a ship full of Africans to Mobile and not get caught. Locally the bet was joined by the builder of the Clotilda, a schooner which was disguised as an innocuous cargo ship. In March, 1860, the schooner left Mobile and set sail to Ouidah. After 110 slaves were brought on board, the captain of the ship, who was concerned over the local conditions, set sail early without a full load of the 130 he had planned on. The captives, which included Cudjo, were farmers, fishermen, hunters, prisoners of war, or victims of kidnapping that came from various parts of the region, who spoke different languages and who had different cultural experiences and traditions. The Clotilda arrived in the Mobile area after seventy days at sea and the captives, who had been kept confined under horrendous conditions, were then transferred to a second ship, the Czar. The Clotilda was then burned and scuttled in Mobile Bay to destroy any evidence of the illegal slave trade.

Once in Mobile, the Africans were either sold and taken to Selma, Alabama or were split up among those making the bet and taken to their plantations to work or at their shipyard or lumber mills in the Mobile area .

According to the Hurston interviews with Cudjo, he along with the rest of the enslaved Africans, always had the collective desire to return to their homeland. In April, 1865, at the end of the Civil War, Cudjo was approached by a Union soldier informing him that he was now a free man. Even though he was now free, he and the others in the Clotilda group did not wish to remain in America. To pay for their trip back to Africa, they agreed to take on jobs, primarily in their former "owners" lumber mill and pool any of the money they made; but they fell short of this goal.

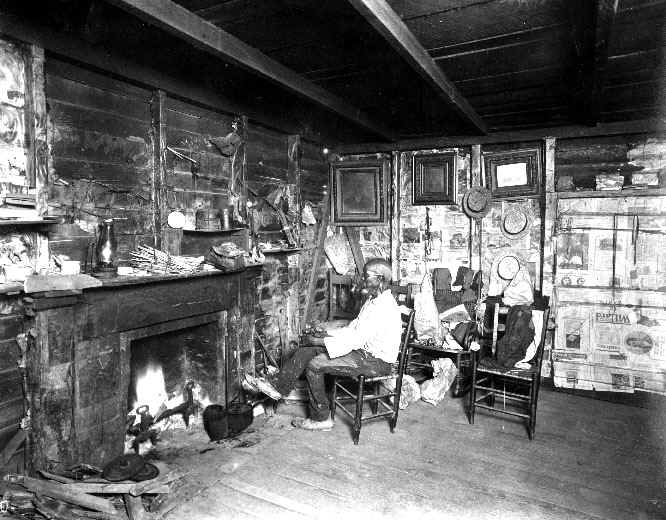

As survivors of the Clotilda slave ship and having come to the realization that they would have to remain in Alabama, land acquisition became paramount and Cudjo was chosen as their group leader to express their wishes to their former "owner". On behalf of the survivors of the Clotilda, Cudjo approached his former "owner" with the idea that since he had stripped the Clotilda Africans of their ancestral land, land should be given to them on which they could further develop their own community. This request was refused and the group was required to pay rent for the parcels of land located in the Magazine Point – Plateau area on the then northern edge of the City of Mobile. In 1868, these parcels were known collectively as Africa Town; and by 1870, the Clotilda Africans began to use the money they made in the mills to actually purchase the land. The community thrived. Under Cudjo's leadership, the group established the African Church, later known as the Old Landmark Church or the Union Baptist Church as it is known today. In 1876, they established the Africatown Graveyard, later known as the Plateau Cemetery, or more commonly referred to as the Old Plateau Cemetery. By 1880 they had also constructed a public school in the community which was the foundation that later became known as the Mobile County Training School .

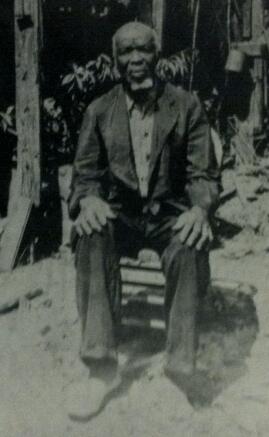

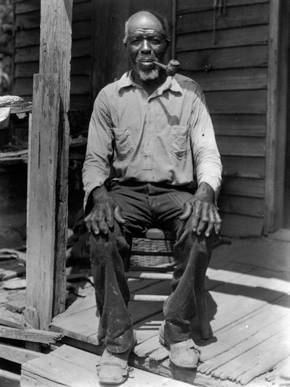

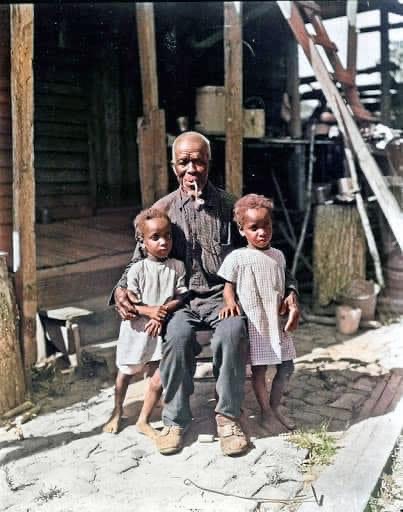

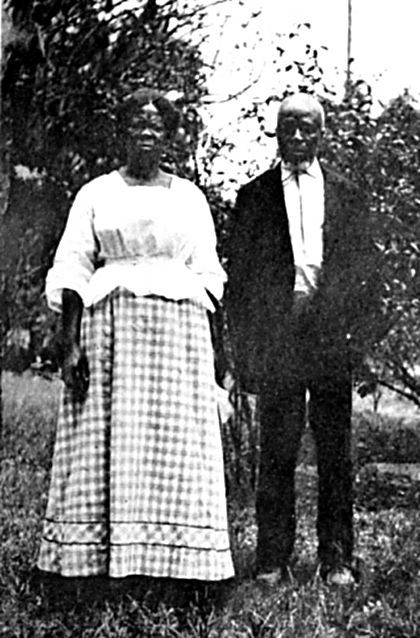

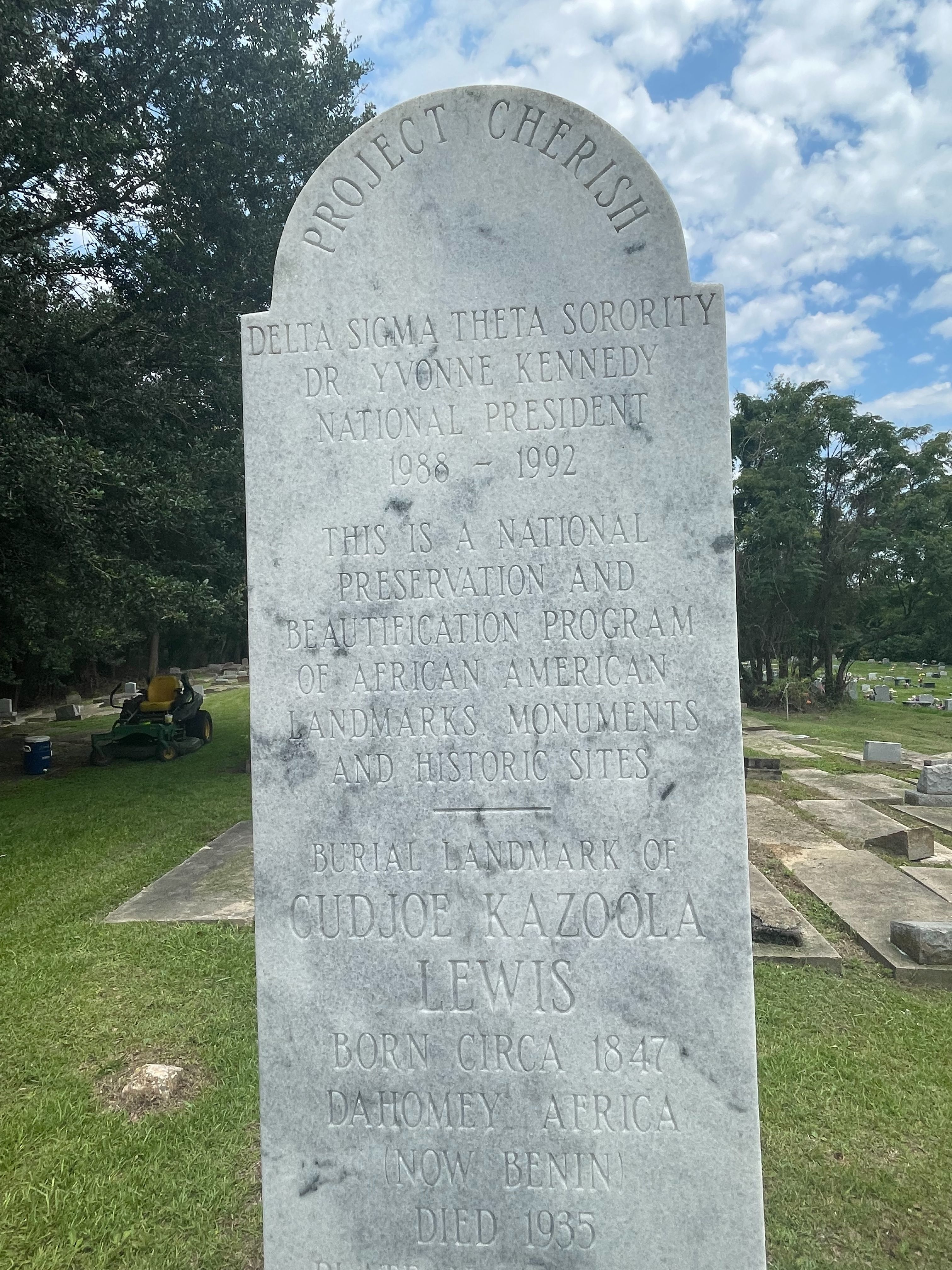

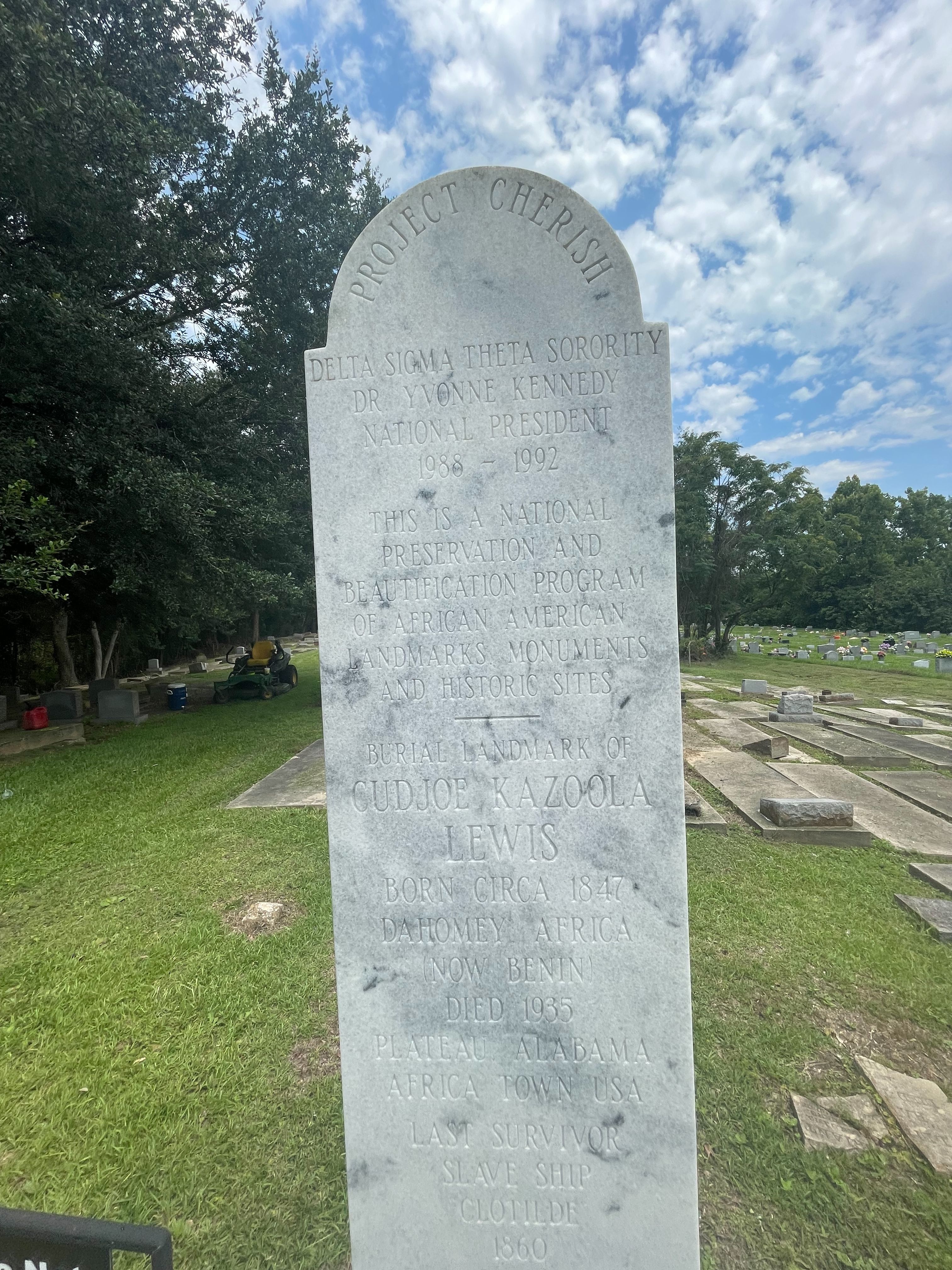

In the mid 1860s, Cudjo married Abila, also referred to as Celie, who was another survivor of the Clotilda, and according to the 1880 United States Census, the couple had six children -- five sons and one daughter. With the passage of the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution in July, 1868, native-born former slaves became United States citizens. Since Cudjo and the other Clotilda survivors were foreign born, this change in status did not apply to them. However, Cudjo did become a naturalized American citizen on October 24, 1868. Cudjo died on July 26, 1935 in Plateau, Alabama, having outlived his wife as well as his six children and was buried in Old Plateau Cemetery. He was one of the last survivors of the Clotilda, with only two other survivors who were young children on the Clotilda outliving him. Although his actual grave has not been located, a commemorative marker was erected in the cemetery in 1990 recognizing his final resting place as well as honoring him as one of the last survivors of the Clotilda slave ship and for his contributions to the then vibrant community he helped create and which is known today as Africatown.

Despite the circumstances that brought Cudjo and his shipmates to Alabama, he and the other survivors were able to build a self-contained independent black community that flourished based on their knowledge and strengths that they had inherited from their African ancestors. Cudjo's descendants as well as those of all the other survivors of the voyage continue to keep his dreams alive today across all walks of their lives, careers, and professions in not only Mobile but beyond. Since his death, Cudjo's status as one of the last Clotilda survivors has made him a prominent figure in the history of the community with regular visits as early as 1999 by representatives of the Government of Benin and NGO's working on a Benin House and as recent as 2018 when the cornerstone for a monument in memory of Cudjo (Kussola Oluale) Lewis was laid in Bante, Republic of Benin. The Africa Town that he and the survivors of the Clotilda settled and whose descendants continue to shepherd to this day resulted in "The Africatown Historic District" being affirmed as significant by the state and the National Park Service, and was listed on the National Register of Historic Places on December 4, 2012. Given the origins and the history of the freed slaves buried in the Old Plateau Cemetery it was recognized in 2010 by the Alabama Historical Commission Cemetery Program as a historical cemetery with a historical marker installed in 2010 by The African-American Heritage Trail of Mobile. National and global awareness grew rapidly as well in part due to the 2018 release of his story as told by Zora Hurston in her book Barracoon: The Story of the Last "Black Cargo." Also in 2018 through the efforts of a local journalist, the University of Southern Mississippi, the Alabama Historical Commission, National Geographic Society, Search, Inc., and the Smithsonian's National Museum of African American History and Culture Slave Wrecks Project (SWP), the remains of the slave ship Clotilda were located reaffirming the history as told by Cudjo and his descendants and those of the other survivors. On May 23, 2019, the following announcement was made by the Smithsonian's National Museum of African American History and Culture. "A critically important chapter in the history of the international slave trade opened this week with the discovery of the charred and submerged remains of the Clotilda, a wooden ship that carried 110 enslaved Africans from the west coast of Africa into Alabama's Mobile Bay in the autumn of 1860. One person died aboard ship, the remaining 109 were taken off ship and moved inland and sold into slavery."

The descendants of Mr. Lewis as well as those of the other survivors of the last slave ship have gone on to become educators, lawyers, doctors, US Armed Forces Veterans, or civil rights leaders, as vital members of communities from the City of Mobile, the County, the State of Alabama as well across the nation and around the world. The wreck of the Clotilda and Cudjo Lewis' story is now helping to carry the dreams and memories and story of Africatown to the attention of the world. The Africatown Heritage House will officially open July 8, 2023 followed by the Africatown Welcome Center where visitors from around the world will learn of the dreams of Africa and stories of Mr. Lewis, the survivors of the Last Slave Ship Clotilda and Africatown

Mr. Lewis is both a significant and notable historical figure as an African brought to the United States in the final days of the slave trade, and one of the founders of Africa Town USA (known today as Africatown). This community of the last African slaves illegally brought to the US in 1860 is nationally recognized for its cultural and heritage significance and their contributions to the American story. According to the National Park Service National Register of Historic Places, Africatown was significant for this national heritage site designation as it "was the first settlement founded by Africans who built their very own town on their own land in the United States.". As an elder Mr. Lewis became a leader of this community that, following many struggles affecting such communities, is remembered and featured in a documentary produced by Netflix in 2022 titled "Descendant". The story of the Clorilda and its rediscovery in 2018 has brought global recognition to the efforts of Mr. Lewis, the survivors of this voyage and the community which they built.

The life of Cudjo Lewis is a complex story that reflects the social, cultural and political history of the time period. His life's story spans two continents. Centered around an illegal bet by two American businessmen a continent away from his home in Africa, he endures the hardship of captivity aboard the slave ship Clotilda, then according to accounts, the unfulfilled dream of returning to his homeland, and culminates in the founding and building of a community called Africa Town. Today the history is told by his descendants both in the US and in his homeland in West Africa.

As told by the noted historian and author Zora Neale Hurston (in her 2018 book Barracoon,The Story Of The Last "Black Cargo''), Cudjo Lewis, or Oluale Kossola as he was known by his African name, was born around 1841 in Bante in West Africa to Oluale and Fondlolu. As noted in Hurston's interviews with Mr. Lewis, he trained as a soldier and by the age of fourteen, he became skilled in hunting and tracking and had acquired expertise in shooting arrows and throwing spears and had gained respect and recognition in his community.

Although a US law was passed in 1808 abolishing the trans-Atlantic slave trade, by all accounts the practice continued over the next fifty years. According to multiple sources the slave trade which was strong at the time in Africa resulted in raids of Cudjo's town of Bante. Cudjo, who was captured along with others in the community, was then taken to Ouidah known as the "Slave Coast" in West Africa in what is present day Benin. The captives were held in barracoons or barrack like structures while awaiting transportation across the Atlantic.

Reports on the activities that were taking place in this region reached the newspapers in Mobile, Alabama in November, 1858 and caught the attention of a wealthy local slave trader and plantation owner in Mobile, Alabama. In defiance of the law a bet was made that he could bring a ship full of Africans to Mobile and not get caught. Locally the bet was joined by the builder of the Clotilda, a schooner which was disguised as an innocuous cargo ship. In March, 1860, the schooner left Mobile and set sail to Ouidah. After 110 slaves were brought on board, the captain of the ship, who was concerned over the local conditions, set sail early without a full load of the 130 he had planned on. The captives, which included Cudjo, were farmers, fishermen, hunters, prisoners of war, or victims of kidnapping that came from various parts of the region, who spoke different languages and who had different cultural experiences and traditions. The Clotilda arrived in the Mobile area after seventy days at sea and the captives, who had been kept confined under horrendous conditions, were then transferred to a second ship, the Czar. The Clotilda was then burned and scuttled in Mobile Bay to destroy any evidence of the illegal slave trade.

Once in Mobile, the Africans were either sold and taken to Selma, Alabama or were split up among those making the bet and taken to their plantations to work or at their shipyard or lumber mills in the Mobile area .

According to the Hurston interviews with Cudjo, he along with the rest of the enslaved Africans, always had the collective desire to return to their homeland. In April, 1865, at the end of the Civil War, Cudjo was approached by a Union soldier informing him that he was now a free man. Even though he was now free, he and the others in the Clotilda group did not wish to remain in America. To pay for their trip back to Africa, they agreed to take on jobs, primarily in their former "owners" lumber mill and pool any of the money they made; but they fell short of this goal.

As survivors of the Clotilda slave ship and having come to the realization that they would have to remain in Alabama, land acquisition became paramount and Cudjo was chosen as their group leader to express their wishes to their former "owner". On behalf of the survivors of the Clotilda, Cudjo approached his former "owner" with the idea that since he had stripped the Clotilda Africans of their ancestral land, land should be given to them on which they could further develop their own community. This request was refused and the group was required to pay rent for the parcels of land located in the Magazine Point – Plateau area on the then northern edge of the City of Mobile. In 1868, these parcels were known collectively as Africa Town; and by 1870, the Clotilda Africans began to use the money they made in the mills to actually purchase the land. The community thrived. Under Cudjo's leadership, the group established the African Church, later known as the Old Landmark Church or the Union Baptist Church as it is known today. In 1876, they established the Africatown Graveyard, later known as the Plateau Cemetery, or more commonly referred to as the Old Plateau Cemetery. By 1880 they had also constructed a public school in the community which was the foundation that later became known as the Mobile County Training School .

In the mid 1860s, Cudjo married Abila, also referred to as Celie, who was another survivor of the Clotilda, and according to the 1880 United States Census, the couple had six children -- five sons and one daughter. With the passage of the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution in July, 1868, native-born former slaves became United States citizens. Since Cudjo and the other Clotilda survivors were foreign born, this change in status did not apply to them. However, Cudjo did become a naturalized American citizen on October 24, 1868. Cudjo died on July 26, 1935 in Plateau, Alabama, having outlived his wife as well as his six children and was buried in Old Plateau Cemetery. He was one of the last survivors of the Clotilda, with only two other survivors who were young children on the Clotilda outliving him. Although his actual grave has not been located, a commemorative marker was erected in the cemetery in 1990 recognizing his final resting place as well as honoring him as one of the last survivors of the Clotilda slave ship and for his contributions to the then vibrant community he helped create and which is known today as Africatown.

Despite the circumstances that brought Cudjo and his shipmates to Alabama, he and the other survivors were able to build a self-contained independent black community that flourished based on their knowledge and strengths that they had inherited from their African ancestors. Cudjo's descendants as well as those of all the other survivors of the voyage continue to keep his dreams alive today across all walks of their lives, careers, and professions in not only Mobile but beyond. Since his death, Cudjo's status as one of the last Clotilda survivors has made him a prominent figure in the history of the community with regular visits as early as 1999 by representatives of the Government of Benin and NGO's working on a Benin House and as recent as 2018 when the cornerstone for a monument in memory of Cudjo (Kussola Oluale) Lewis was laid in Bante, Republic of Benin. The Africa Town that he and the survivors of the Clotilda settled and whose descendants continue to shepherd to this day resulted in "The Africatown Historic District" being affirmed as significant by the state and the National Park Service, and was listed on the National Register of Historic Places on December 4, 2012. Given the origins and the history of the freed slaves buried in the Old Plateau Cemetery it was recognized in 2010 by the Alabama Historical Commission Cemetery Program as a historical cemetery with a historical marker installed in 2010 by The African-American Heritage Trail of Mobile. National and global awareness grew rapidly as well in part due to the 2018 release of his story as told by Zora Hurston in her book Barracoon: The Story of the Last "Black Cargo." Also in 2018 through the efforts of a local journalist, the University of Southern Mississippi, the Alabama Historical Commission, National Geographic Society, Search, Inc., and the Smithsonian's National Museum of African American History and Culture Slave Wrecks Project (SWP), the remains of the slave ship Clotilda were located reaffirming the history as told by Cudjo and his descendants and those of the other survivors. On May 23, 2019, the following announcement was made by the Smithsonian's National Museum of African American History and Culture. "A critically important chapter in the history of the international slave trade opened this week with the discovery of the charred and submerged remains of the Clotilda, a wooden ship that carried 110 enslaved Africans from the west coast of Africa into Alabama's Mobile Bay in the autumn of 1860. One person died aboard ship, the remaining 109 were taken off ship and moved inland and sold into slavery."

The descendants of Mr. Lewis as well as those of the other survivors of the last slave ship have gone on to become educators, lawyers, doctors, US Armed Forces Veterans, or civil rights leaders, as vital members of communities from the City of Mobile, the County, the State of Alabama as well across the nation and around the world. The wreck of the Clotilda and Cudjo Lewis' story is now helping to carry the dreams and memories and story of Africatown to the attention of the world. The Africatown Heritage House will officially open July 8, 2023 followed by the Africatown Welcome Center where visitors from around the world will learn of the dreams of Africa and stories of Mr. Lewis, the survivors of the Last Slave Ship Clotilda and Africatown

Bio by: Georgeann Ellis

Family Members

Advertisement

See more Lewis memorials in:

Explore more

Sponsored by Ancestry

Advertisement