Courtly Tone In Shaping The Times, Dies at 87

Contributor #49733433 suggested additional Bio information:

Clifton Daniel, a Managing Editor Who Set a Writerly,

Courtly Tone In Shaping The Times, Dies at 87

ERIC PACE, New York Times, February 22, 2000

Clifton Daniel, the courtly North Carolinian who served as managing editor of The New York Times from 1964 to 1969 after a career as a correspondent in wartime London, war-torn Europe and the Middle East, died yesterday at his home in Manhattan. He was 87. The cause was complications of a stroke and heart disease, said his wife, Margaret Truman Daniel.

Mr. Daniel's long, adventuresome and many-sided professional life was once summed up in a magazine profile with the headline ''Up From Zebulon.'' Zebulon was the tiny lumber mill town in northeastern North Carolina where he was born and reared and where his parents saved the income from the family drugstore to put him through college in the Depression. A small-town Southern background was something that Mr. Daniel shared with his predecessor as managing editor, Turner Catledge, who was from Philadelphia, Miss. And when Mr. Daniel was married in 1956, after many footloose years in Europe and the Middle East, it was to a down-to-earth young woman whose father, like Mr. Daniel's, had worked as a shopkeeper far away from Times Square. The bride was Margaret Truman, the only child of former President Truman, who had run a haberdashery in Missouri. ''We had a lot in common,'' Mr. Daniel wrote in his volume of reminiscences, ''Lords, Ladies and Gentlemen,'' which appeared in 1984. ''We were the kind of people who wouldn't marry anybody our mothers wouldn't approve of; a couple of citified small-towners, puritans among the fleshpots.''

Mr. Daniel rose to be assistant to the managing editor, assistant managing editor and then managing editor. In that post he was the senior news executive of the daily Times, outranked only by Mr. Catledge, the executive editor, who oversaw daily and Sunday departments from a vantage outside the newsroom. As managing editor, Mr. Daniel sought to brighten the newspaper with pungent writing, eye-catching photography and an emphasis on what many newspaper editors of the time disparaged as ''soft news.'' Mr. Daniel intensified the newspaper's treatment of society news, arts coverage and obituaries. Society news, which had been mainly dry wedding and engagement announcements, began to burst with spicy detail, human interest and social insights. Cultural coverage studied the flaws as well as the fame of important artists. Obituaries became less reverent. In 1969, Mr. Daniel was succeeded as managing editor by A. M. Rosenthal and became an associate editor, remaining in New York for four more years and working in a different area of journalism, as a commentator on The Times's radio station, WQXR. Then the Daniels moved to Washington, where Mr. Daniel worked as chief of the newspaper's bureau until 1976. Earlier in his career Mr. Daniel had won respect as a foreign correspondent on some grueling and unsettling assignments for The Times. In Moscow in 1954 and 1955, for example, he was the only permanent correspondent of a Western non-communist newspaper in the Soviet Union.

-

Among his colleagues, Mr. Daniel was known for an ability to imbue his writing with a strong feeling for the places and people he had seen. Of a drive through the Soviet Union, he wrote that he had found ''a Russia that Tolstoy never knew,'' where ''factories seen across the fields and mines with towering slag heaps are giving off steam and smoke,'' where ''hitchhikers, creatures of the motor age, are on the road with bundles and thumbs uplifted,'' while ''strung out mile after mile along the highway is a convoy of new trucks.'' In Moscow, Mr. Daniel took his readers to the Bolshoi Theater, ''an ornate and refurnished relic of 19th-century Russia'' with ''burnished gilt balconies and vivid red draperies,'' where ''Muscovites circled the foyer in pairs between the acts, seeing and being seen, keeping in line and in step, as if arranging themselves for a quadrille . . . plain people, the women generally in flowered print dresses, the men in uniforms or the sober garb of civil servants.'' From Cologne, West Germany, Mr. Daniel described carnival time: ''In the twisting narrow streets that run around the twin spires of the city's famous cathedral, hundreds of thousands of spectators swayed, rocked and sang and danced. They cheered the brilliant costumes [and] scrambled for barrelfuls of candy that were thrown at them. Any girl who could be caught could be kissed and several policemen were tossed in the air by a gang of young men.''

Breathing New Life Into News Pages

When Mr. Daniel became managing editor, he gave a gifted reporter, Charlotte Curtis, a mandate to write about society as news, encouraging her to provide shrewd and sometimes impudent reporting about high society and high life. Ms. Curtis continued that society reporting after she was promoted in 1965 to be the editor of women's news. Her title was changed in 1971 to family/style editor, and she held the position until 1974. Ms. Curtis worked under Mr. Daniel for nine years, until 1969, and strove to expand coverage of fashion, society, decor and family matters to reflect the conviction she shared with Mr. Daniel that those topics should be treated with the same emphasis on news and lively writing that politics and sports received. It was Mr. Daniel who nurtured the career of The Times's food writer, Craig Claiborne, and helped him become one of the nation's best-known restaurant critics. Mr. Daniel also set about improving obituaries in The Times. He found them written in such a gray, lifeless way that he was said to have remarked, ''It seemed as though the subjects had never been alive.'' He sought to make them longer, more authoritative and more vivid; to help bring that about, he chose Alden Whitman as chief obituary writer. Mr. Whitman recalled that Mr. Daniel told him, ''We interview people about everything else, why shouldn't we interview them for their obituaries?'' Mr. Daniel encouraged Mr. Whitman to travel and talk to accomplished people solely for their future obituaries, often with their full knowledge of the purpose. That had rarely been done before, and Mr. Daniel proposed that Mr. Whitman begin by interviewing Mr. Daniel's father-in-law, the former president. Soon Mr. Whitman found himself facing Truman, who told him, ''I know why you are here and I want to help you all I can.'' In the years that followed, Mr. Whitman interviewed figures like Earl Warren, Charles Chaplin, Charles A. Lindbergh, Graham Greene and Anthony Eden. His method resulted in comprehensive obituaries that would be written in advance to be ready for publication at short notice when the subjects died. It also resulted in the presentation of a special Polk Memorial Award to Mr. Whitman in 1980 for ''setting new standards of excellence at what had been a routine assignment.''

Mr. Daniel relished his role in expanding The Times's coverage of arts news. ''Any newspaper that didn't cover a major industry in its community would be judged derelict,'' he said. ''I thought the coverage should be conscientious, thoughtful and thorough.'' He also thought that critics working for The Times should not express their views so vehemently that they seemed to be carrying on vendettas. And in 1968, when The Times retained a long-haired culture writer as a rock critic, Mr. Daniel enjoyed breaking the news gently to the well-groomed former marine who was then the paper's publisher, Arthur Ochs Sulzberger. ''His name is Mike Jahn,'' Mr. Daniel wrote in a note to Mr. Sulzberger, ''and he is going to write pieces on folk/rock music.'' Mr. Daniel went on to report that another editor had reassured him: ''Mr. Jahn wears his hair in a somewhat bizarre style -- in fact he looks like a werewolf. But since his work will not require him to be in the office very much, I don't think he'll bite any of us.'' Sheik of Fleet Street And a Wastrel King Much of Mr. Daniel's interest in society and the arts took root while he was reporting in World War II from London, where he was remembered not only for his professionalism but also for his savoir-faire. Indeed, during Mr. Daniel's London years, he became known as the Sheik of Fleet Street. And London tailors made the fur-lined, karakul-collared greatcoat that he later wore on cold days in the Soviet Union, where his reporting won him an Overseas Press Club award.

Despite Mr. Daniel's worldliness, his table manners failed to satisfy the dissolute King Farouk of Egypt. ''Mr. Daniel,'' the King said at a luncheon in Cairo in 1946, ''would you mind not clicking your fork against your teeth?'' Mr. Daniel answered politely enough: ''I'm sorry, sir. I shall try to eat more quietly.'' But two decades later, in his volume of reminiscences, he observed, ''Farouk's was a wasted life.'' Reviewing that book in The New York Times, John Brooks said of Mr. Daniel, ''Like a modern Scarlet Pimpernel, he enjoys wearing the masque of a dandy'' and ''seems intent on playing down the fact that, dinner parties aside, his has been a life of serious hard work.''

In a 1995 book, ''Growing Up With My Grandfather,'' Mr. Daniel's eldest son, Clifton Truman Daniel, wrote, ''Dad is so impeccable that even in his undershirt he looks almost formal.'' Mr. Daniel did not hesitate to telephone The Times's society news desk to set the chaps there straight on esoteric details of British fox-hunting garb. In two memorandums long famous within The Times, he listed the exact gradations of men's formal wear and all their proper accessories. In one, he distinguished between ''a black silk hat called a top hat,'' worn at formal daytime occasions with a morning coat or cutaway, and the kind worn to a formal evening affair with a tailcoat: ''The hat properly worn with this suit is an opera hat -- a folding silk hat of grosgrain material -- but almost nobody owns one these days.'' In the other, he concluded, ''Finally, it used to be that formal evening dress along the Persian Gulf or the Red Sea consisted of black trousers, a cummerbund and a short-sleeved white shirt with an open collar. It was too hot to wear a jacket and tie.'' He was aghast when a young reporter confused the names of two former Saudi monarchs, Ibn Saud and just plain Saud. But veteran journalists remember Mr. Daniel's perceptive coverage of the lives of ordinary people in the Soviet Union while he was a correspondent. Admirers say he led the way in presenting American readers, who were conditioned by cold-war tensions and fears, with a humanized portrayal of Russian daily life in the period after Stalin's death in 1953.

Elbert Clifton Daniel Jr. was born on Sept. 19, 1912, the son of Elbert Clifton Daniel and Elvah Jones Daniel and a great-grandson of Zachariah G. Daniel, an illiterate farmer who came to the United States from England. In those days Zebulon had a population of 500. As a teenager, young E. C., as he was known, worked part time for his father, an enterprising druggist who was mayor of Zebulon, the first person in town to own a telephone, and later the head of the North Carolina Pharmaceutical Association. Years later, in a speech at the University of North Carolina, Mr. Daniel gave this account of how he first became a reporter: ''I read one of those articles in a boys' magazine on 'Choosing a Career.' It said that if you wanted to be a newspaperman, if you wanted to write, the best thing to do was to start writing. It didn't say anything about going to journalism school. It just said, 'Send in something to the local paper.' So I did. As I remember, it was an account of a basketball game. It got printed. Having one item published was enough to convince me that I was God's gift to journalism. I was pretty soon writing all the local news in The Record during summer vacations from school.'' Journalism School Was a Drugstore Working in the drugstore, Mr. Daniel told his audience, ''was a lucky coincidence, because there was no better place in the town to gather news.'' ''The chief of police and the deputy sheriff used to hang around there all the time,'' he continued. ''We took calls for the doctors. Visiting politicians dropped in to shake hands. Farmers talked about the price of tobacco and cotton. ''In fact, nearly everybody in town went down to the drugstore for one reason or another during the week. I can still remember one night when a fellow walked in, apparently holding his head on with his hands. His throat was cut from ear to ear. I got a doctor for him -- and a story for The Record.''

After graduating from Wakelon High School in Zebulon, Mr. Daniel entered the University of North Carolina. He became editor of the campus literary magazine and vice president of the student body, and received his B.A. degree in 1933. Then he put in a year as associate editor of The Dunn Daily Bulletin in North Carolina before spending four years as a reporter, political writer and columnist for The News and Observer in Raleigh, the state capital. In 1937, after trying unsuccessfully to be hired by The Times, Mr. Daniel went to work for The Associated Press in New York. One of his friends in the city was the writer Thomas Wolfe, a fellow North Carolinian, whose turbulent second novel, ''Of Time and the River,'' had come out in 1935. The two men would sometimes meet for a late supper in the theater district, then stroll the streets for hours, talking about literature and life. Mr. Daniel spent seven years as a reporter and editor with The A.P. and was transferred from New York to Washington, and then to Bern and London.

In 1944, he was hired by The Times and stayed on in London, covering the Supreme Headquarters of the Allied Expeditionary Force. Later, he followed the advance of the First Army into Belgium and Germany. Early in 1945 he was in Paris, and one of his dispatches included these lines: ''The big dirty green trucks speed along the Rue La Fayette, their heavy tires singing on the cobblestones and their canvas tops snapping in the winter wind. The men in the back are tired and cramped after 11 hours on the road. The last wisecrack was made a hundred miles back. But one of them peers out, sees the name of the street and says, 'La Fayette, we're here.' '' Years later, Mr. Daniel recalled in an interview: ''I had what the British used to call 'a good war.' I enjoyed my war and I survived without a scratch.'' After the guns fell silent, he became The Times's chief correspondent in the Middle East and traveled widely, reporting on Arab nationalism, on tension and violence in Egypt and what is now Israel and in late 1946 on the collapse of a Soviet-backed rebel regime in northern Iran, where he found himself ahead of the story he had come to cover. Driving in a borrowed jeep, he and two other correspondents arrived in Tabriz, the main north Iranian city, hours ahead of the Iranian government force that was to take over. The newsmen got a tumultuous greeting from excited throngs along their route, and sheep were sacrificed in their honor. But they soon saw there was no conventional way of sending their dispatches from Tabriz to the outside world. And so they gently commandeered the local radio station and broadcast the news to the world -- and to their editors. Later Mr. Daniel returned to London and covered the death of King George VI and the coronation of Queen Elizabeth II. ''The coronation was the greatest spectacle I've ever seen,'' he said afterward. ''It was probably the last time that the British would be able to mount such a production; they were losing their place as an imperialist power.'' A Pivotal Struggle And a New Path

After his assignments overseas, Mr. Daniel returned to New York and began the editing apprenticeship that led to the managing editor's chair. He had occupied it for four years when a climactic event occurred in The Times's newsroom management, one that ultimately chilled his relationship with the publisher, Arthur Ochs Sulzberger. Mr. Daniel and the two other highest-ranking editors, Mr. Catledge and Mr. Rosenthal, had become dissatisfied with the leadership of the newspaper's Washington bureau, staffed by award-winning proteges of James Reston, the columnist and former bureau chief. The three New York editors decided that they wanted James L. Greenfield, an editor recently hired in the home office, to replace Tom Wicker as the bureau chief. Mr. Greenfield had previous experience in Washington, as a correspondent and a government official. Mr. Sulzberger endorsed his appointment, but it was strongly opposed by Mr. Wicker, by members of the bureau and above all by Mr. Reston. They appealed, and Mr. Sulzberger changed his mind, keeping Mr. Wicker as bureau chief. Mr. Daniel complained to Mr. Sulzberger so angrily about the change of plan that the publisher was offended. Late in 1968, Mr. Wicker stepped aside to write his column full time. He was succeeded by Max Frankel, a bureau member who went on to become executive editor of The Times. Mr. Greenfield, meanwhile, quit the paper. But he was rehired in 1969 as foreign editor and rose to be an assistant managing editor. Mr. Daniel, though, never regained his standing with the publisher. After yielding the managing editor's post in 1969, Mr. Daniel worked in television as well as radio. His assignments included supervising The Times News Service, directing special projects and continuing his service as moderator of a twice-monthly program called ''News in Perspective'' produced by National Educational Television in association with The Times. Mr. Daniel also presided over two radio programs, ''Insight'' and ''One Man's Opinion,'' for WQXR.

Returning to the news staff as head of the Washington bureau, he wrote analytical articles and oversaw the coverage of President Richard M. Nixon's resignation and the outset of Gerald R. Ford's presidency. He concentrated much of his effort on developing a staff for investigative reporting.

Of Murder Mysteries And Truman's Ghost

He also watched his wife's literary career with pride. Margaret Truman Daniel wrote or edited a score of books under the Truman name. After her first mystery novel, ''Murder in the White House,'' became a best seller in 1980, she said in an interview, ''My husband tells me to stick to what I know.'' Her later books have included ''Murder on Capitol Hill'' and ''Murder in the Supreme Court.'' Their son Clifton Truman Daniel asserted in his memoir: ''My mother seems to have a strong opinion, often bad, of almost everyone in Washington. That's why she writes those murder mysteries; so she can kill them all off, one at a time.''

The Daniels had three other sons -- William Wallace, Harrison Gates and Thomas Washington. Late in life the couple saw their home life laid open publicly in a way that was unsettling. In his book, young Clifton, who was a writer for a North Carolina newspaper before becoming an official of Harry S. Truman Community College in Chicago, gave this summary of the problem he said stemmed from having President Truman for a grandfather: ''Grandpa Truman died when I was 15 and I spent my next 11 years wondering how to live up to him. Only I didn't realize that's what I was doing. The only thing I had to show for it was a string of failed academic courses, lost jobs, and hangovers. ''Over the next 10 years,'' he added, ''I found that though I had let my grandfather's fame bring me down, I could look to him to lift me up again. All he would have wanted for me was my happiness.'' Clifton Truman Daniel also wrote that his parents were strict with him and his brothers in other ways because Truman had been president. ''They didn't want us to get the idea that, just because of our grandfather, we could go through life getting something for nothing,'' he observed. ''Looking back, I can see what they were worried about. But keeping us from getting swelled heads often meant bruising our egos.''

In 1977, having reached 65, Mr. Daniel ended his newspaper career and told an interviewer, ''There's no profession that offers you more variety in life or more excitement.'' In addition to his wife and sons, he is survived by five grandchildren. In retirement, Mr. Daniel enjoyed the conviviality of his club, the Century Association, near the Times Building on West 43rd Street. He did not stop writing and went on to be the editor in chief of the book ''Chronicle of the 20th Century.'' Its first edition, a best seller, was published in 1987. The book was a weighty collection of two million words and 3,700 illustrations that listed a news event for almost every day of the 20th century to the end of 1986. Almost all the headlines in the book, and a few of the articles, were written by Mr. Daniel. In an interview in 1987, he said of those articles: ''When something came along where I had some knowledge, I pitched in. I wrote the Hall-Mills murder case because none of the editors had ever heard of it. I also was the only one who seemed to know the details about the Earl of Rosebery, who achieved the three things he wanted in life -- to win the English Derby, marry England's richest heiress and become prime minister.''

Courtly Tone In Shaping The Times, Dies at 87

Contributor #49733433 suggested additional Bio information:

Clifton Daniel, a Managing Editor Who Set a Writerly,

Courtly Tone In Shaping The Times, Dies at 87

ERIC PACE, New York Times, February 22, 2000

Clifton Daniel, the courtly North Carolinian who served as managing editor of The New York Times from 1964 to 1969 after a career as a correspondent in wartime London, war-torn Europe and the Middle East, died yesterday at his home in Manhattan. He was 87. The cause was complications of a stroke and heart disease, said his wife, Margaret Truman Daniel.

Mr. Daniel's long, adventuresome and many-sided professional life was once summed up in a magazine profile with the headline ''Up From Zebulon.'' Zebulon was the tiny lumber mill town in northeastern North Carolina where he was born and reared and where his parents saved the income from the family drugstore to put him through college in the Depression. A small-town Southern background was something that Mr. Daniel shared with his predecessor as managing editor, Turner Catledge, who was from Philadelphia, Miss. And when Mr. Daniel was married in 1956, after many footloose years in Europe and the Middle East, it was to a down-to-earth young woman whose father, like Mr. Daniel's, had worked as a shopkeeper far away from Times Square. The bride was Margaret Truman, the only child of former President Truman, who had run a haberdashery in Missouri. ''We had a lot in common,'' Mr. Daniel wrote in his volume of reminiscences, ''Lords, Ladies and Gentlemen,'' which appeared in 1984. ''We were the kind of people who wouldn't marry anybody our mothers wouldn't approve of; a couple of citified small-towners, puritans among the fleshpots.''

Mr. Daniel rose to be assistant to the managing editor, assistant managing editor and then managing editor. In that post he was the senior news executive of the daily Times, outranked only by Mr. Catledge, the executive editor, who oversaw daily and Sunday departments from a vantage outside the newsroom. As managing editor, Mr. Daniel sought to brighten the newspaper with pungent writing, eye-catching photography and an emphasis on what many newspaper editors of the time disparaged as ''soft news.'' Mr. Daniel intensified the newspaper's treatment of society news, arts coverage and obituaries. Society news, which had been mainly dry wedding and engagement announcements, began to burst with spicy detail, human interest and social insights. Cultural coverage studied the flaws as well as the fame of important artists. Obituaries became less reverent. In 1969, Mr. Daniel was succeeded as managing editor by A. M. Rosenthal and became an associate editor, remaining in New York for four more years and working in a different area of journalism, as a commentator on The Times's radio station, WQXR. Then the Daniels moved to Washington, where Mr. Daniel worked as chief of the newspaper's bureau until 1976. Earlier in his career Mr. Daniel had won respect as a foreign correspondent on some grueling and unsettling assignments for The Times. In Moscow in 1954 and 1955, for example, he was the only permanent correspondent of a Western non-communist newspaper in the Soviet Union.

-

Among his colleagues, Mr. Daniel was known for an ability to imbue his writing with a strong feeling for the places and people he had seen. Of a drive through the Soviet Union, he wrote that he had found ''a Russia that Tolstoy never knew,'' where ''factories seen across the fields and mines with towering slag heaps are giving off steam and smoke,'' where ''hitchhikers, creatures of the motor age, are on the road with bundles and thumbs uplifted,'' while ''strung out mile after mile along the highway is a convoy of new trucks.'' In Moscow, Mr. Daniel took his readers to the Bolshoi Theater, ''an ornate and refurnished relic of 19th-century Russia'' with ''burnished gilt balconies and vivid red draperies,'' where ''Muscovites circled the foyer in pairs between the acts, seeing and being seen, keeping in line and in step, as if arranging themselves for a quadrille . . . plain people, the women generally in flowered print dresses, the men in uniforms or the sober garb of civil servants.'' From Cologne, West Germany, Mr. Daniel described carnival time: ''In the twisting narrow streets that run around the twin spires of the city's famous cathedral, hundreds of thousands of spectators swayed, rocked and sang and danced. They cheered the brilliant costumes [and] scrambled for barrelfuls of candy that were thrown at them. Any girl who could be caught could be kissed and several policemen were tossed in the air by a gang of young men.''

Breathing New Life Into News Pages

When Mr. Daniel became managing editor, he gave a gifted reporter, Charlotte Curtis, a mandate to write about society as news, encouraging her to provide shrewd and sometimes impudent reporting about high society and high life. Ms. Curtis continued that society reporting after she was promoted in 1965 to be the editor of women's news. Her title was changed in 1971 to family/style editor, and she held the position until 1974. Ms. Curtis worked under Mr. Daniel for nine years, until 1969, and strove to expand coverage of fashion, society, decor and family matters to reflect the conviction she shared with Mr. Daniel that those topics should be treated with the same emphasis on news and lively writing that politics and sports received. It was Mr. Daniel who nurtured the career of The Times's food writer, Craig Claiborne, and helped him become one of the nation's best-known restaurant critics. Mr. Daniel also set about improving obituaries in The Times. He found them written in such a gray, lifeless way that he was said to have remarked, ''It seemed as though the subjects had never been alive.'' He sought to make them longer, more authoritative and more vivid; to help bring that about, he chose Alden Whitman as chief obituary writer. Mr. Whitman recalled that Mr. Daniel told him, ''We interview people about everything else, why shouldn't we interview them for their obituaries?'' Mr. Daniel encouraged Mr. Whitman to travel and talk to accomplished people solely for their future obituaries, often with their full knowledge of the purpose. That had rarely been done before, and Mr. Daniel proposed that Mr. Whitman begin by interviewing Mr. Daniel's father-in-law, the former president. Soon Mr. Whitman found himself facing Truman, who told him, ''I know why you are here and I want to help you all I can.'' In the years that followed, Mr. Whitman interviewed figures like Earl Warren, Charles Chaplin, Charles A. Lindbergh, Graham Greene and Anthony Eden. His method resulted in comprehensive obituaries that would be written in advance to be ready for publication at short notice when the subjects died. It also resulted in the presentation of a special Polk Memorial Award to Mr. Whitman in 1980 for ''setting new standards of excellence at what had been a routine assignment.''

Mr. Daniel relished his role in expanding The Times's coverage of arts news. ''Any newspaper that didn't cover a major industry in its community would be judged derelict,'' he said. ''I thought the coverage should be conscientious, thoughtful and thorough.'' He also thought that critics working for The Times should not express their views so vehemently that they seemed to be carrying on vendettas. And in 1968, when The Times retained a long-haired culture writer as a rock critic, Mr. Daniel enjoyed breaking the news gently to the well-groomed former marine who was then the paper's publisher, Arthur Ochs Sulzberger. ''His name is Mike Jahn,'' Mr. Daniel wrote in a note to Mr. Sulzberger, ''and he is going to write pieces on folk/rock music.'' Mr. Daniel went on to report that another editor had reassured him: ''Mr. Jahn wears his hair in a somewhat bizarre style -- in fact he looks like a werewolf. But since his work will not require him to be in the office very much, I don't think he'll bite any of us.'' Sheik of Fleet Street And a Wastrel King Much of Mr. Daniel's interest in society and the arts took root while he was reporting in World War II from London, where he was remembered not only for his professionalism but also for his savoir-faire. Indeed, during Mr. Daniel's London years, he became known as the Sheik of Fleet Street. And London tailors made the fur-lined, karakul-collared greatcoat that he later wore on cold days in the Soviet Union, where his reporting won him an Overseas Press Club award.

Despite Mr. Daniel's worldliness, his table manners failed to satisfy the dissolute King Farouk of Egypt. ''Mr. Daniel,'' the King said at a luncheon in Cairo in 1946, ''would you mind not clicking your fork against your teeth?'' Mr. Daniel answered politely enough: ''I'm sorry, sir. I shall try to eat more quietly.'' But two decades later, in his volume of reminiscences, he observed, ''Farouk's was a wasted life.'' Reviewing that book in The New York Times, John Brooks said of Mr. Daniel, ''Like a modern Scarlet Pimpernel, he enjoys wearing the masque of a dandy'' and ''seems intent on playing down the fact that, dinner parties aside, his has been a life of serious hard work.''

In a 1995 book, ''Growing Up With My Grandfather,'' Mr. Daniel's eldest son, Clifton Truman Daniel, wrote, ''Dad is so impeccable that even in his undershirt he looks almost formal.'' Mr. Daniel did not hesitate to telephone The Times's society news desk to set the chaps there straight on esoteric details of British fox-hunting garb. In two memorandums long famous within The Times, he listed the exact gradations of men's formal wear and all their proper accessories. In one, he distinguished between ''a black silk hat called a top hat,'' worn at formal daytime occasions with a morning coat or cutaway, and the kind worn to a formal evening affair with a tailcoat: ''The hat properly worn with this suit is an opera hat -- a folding silk hat of grosgrain material -- but almost nobody owns one these days.'' In the other, he concluded, ''Finally, it used to be that formal evening dress along the Persian Gulf or the Red Sea consisted of black trousers, a cummerbund and a short-sleeved white shirt with an open collar. It was too hot to wear a jacket and tie.'' He was aghast when a young reporter confused the names of two former Saudi monarchs, Ibn Saud and just plain Saud. But veteran journalists remember Mr. Daniel's perceptive coverage of the lives of ordinary people in the Soviet Union while he was a correspondent. Admirers say he led the way in presenting American readers, who were conditioned by cold-war tensions and fears, with a humanized portrayal of Russian daily life in the period after Stalin's death in 1953.

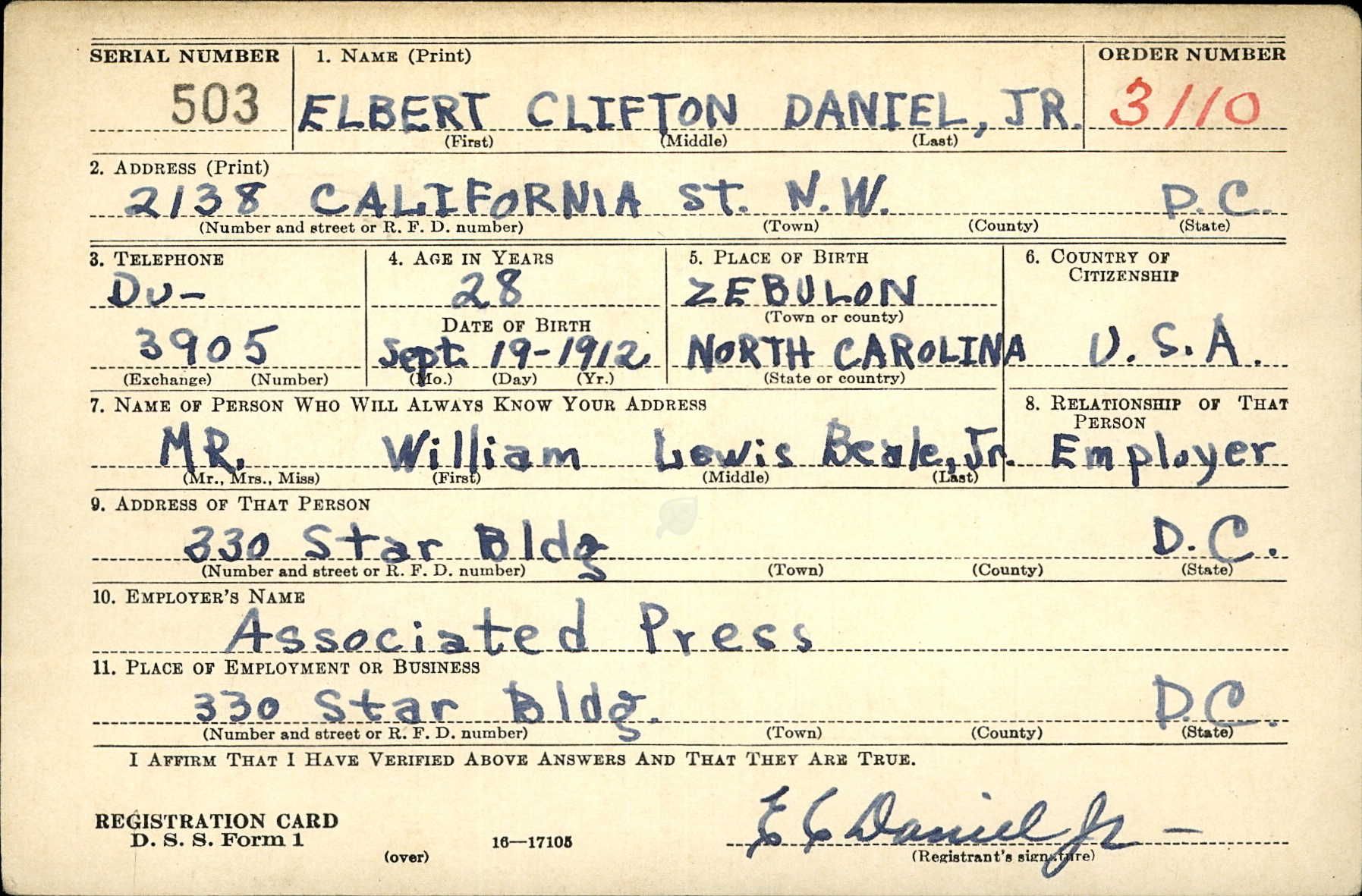

Elbert Clifton Daniel Jr. was born on Sept. 19, 1912, the son of Elbert Clifton Daniel and Elvah Jones Daniel and a great-grandson of Zachariah G. Daniel, an illiterate farmer who came to the United States from England. In those days Zebulon had a population of 500. As a teenager, young E. C., as he was known, worked part time for his father, an enterprising druggist who was mayor of Zebulon, the first person in town to own a telephone, and later the head of the North Carolina Pharmaceutical Association. Years later, in a speech at the University of North Carolina, Mr. Daniel gave this account of how he first became a reporter: ''I read one of those articles in a boys' magazine on 'Choosing a Career.' It said that if you wanted to be a newspaperman, if you wanted to write, the best thing to do was to start writing. It didn't say anything about going to journalism school. It just said, 'Send in something to the local paper.' So I did. As I remember, it was an account of a basketball game. It got printed. Having one item published was enough to convince me that I was God's gift to journalism. I was pretty soon writing all the local news in The Record during summer vacations from school.'' Journalism School Was a Drugstore Working in the drugstore, Mr. Daniel told his audience, ''was a lucky coincidence, because there was no better place in the town to gather news.'' ''The chief of police and the deputy sheriff used to hang around there all the time,'' he continued. ''We took calls for the doctors. Visiting politicians dropped in to shake hands. Farmers talked about the price of tobacco and cotton. ''In fact, nearly everybody in town went down to the drugstore for one reason or another during the week. I can still remember one night when a fellow walked in, apparently holding his head on with his hands. His throat was cut from ear to ear. I got a doctor for him -- and a story for The Record.''

After graduating from Wakelon High School in Zebulon, Mr. Daniel entered the University of North Carolina. He became editor of the campus literary magazine and vice president of the student body, and received his B.A. degree in 1933. Then he put in a year as associate editor of The Dunn Daily Bulletin in North Carolina before spending four years as a reporter, political writer and columnist for The News and Observer in Raleigh, the state capital. In 1937, after trying unsuccessfully to be hired by The Times, Mr. Daniel went to work for The Associated Press in New York. One of his friends in the city was the writer Thomas Wolfe, a fellow North Carolinian, whose turbulent second novel, ''Of Time and the River,'' had come out in 1935. The two men would sometimes meet for a late supper in the theater district, then stroll the streets for hours, talking about literature and life. Mr. Daniel spent seven years as a reporter and editor with The A.P. and was transferred from New York to Washington, and then to Bern and London.

In 1944, he was hired by The Times and stayed on in London, covering the Supreme Headquarters of the Allied Expeditionary Force. Later, he followed the advance of the First Army into Belgium and Germany. Early in 1945 he was in Paris, and one of his dispatches included these lines: ''The big dirty green trucks speed along the Rue La Fayette, their heavy tires singing on the cobblestones and their canvas tops snapping in the winter wind. The men in the back are tired and cramped after 11 hours on the road. The last wisecrack was made a hundred miles back. But one of them peers out, sees the name of the street and says, 'La Fayette, we're here.' '' Years later, Mr. Daniel recalled in an interview: ''I had what the British used to call 'a good war.' I enjoyed my war and I survived without a scratch.'' After the guns fell silent, he became The Times's chief correspondent in the Middle East and traveled widely, reporting on Arab nationalism, on tension and violence in Egypt and what is now Israel and in late 1946 on the collapse of a Soviet-backed rebel regime in northern Iran, where he found himself ahead of the story he had come to cover. Driving in a borrowed jeep, he and two other correspondents arrived in Tabriz, the main north Iranian city, hours ahead of the Iranian government force that was to take over. The newsmen got a tumultuous greeting from excited throngs along their route, and sheep were sacrificed in their honor. But they soon saw there was no conventional way of sending their dispatches from Tabriz to the outside world. And so they gently commandeered the local radio station and broadcast the news to the world -- and to their editors. Later Mr. Daniel returned to London and covered the death of King George VI and the coronation of Queen Elizabeth II. ''The coronation was the greatest spectacle I've ever seen,'' he said afterward. ''It was probably the last time that the British would be able to mount such a production; they were losing their place as an imperialist power.'' A Pivotal Struggle And a New Path

After his assignments overseas, Mr. Daniel returned to New York and began the editing apprenticeship that led to the managing editor's chair. He had occupied it for four years when a climactic event occurred in The Times's newsroom management, one that ultimately chilled his relationship with the publisher, Arthur Ochs Sulzberger. Mr. Daniel and the two other highest-ranking editors, Mr. Catledge and Mr. Rosenthal, had become dissatisfied with the leadership of the newspaper's Washington bureau, staffed by award-winning proteges of James Reston, the columnist and former bureau chief. The three New York editors decided that they wanted James L. Greenfield, an editor recently hired in the home office, to replace Tom Wicker as the bureau chief. Mr. Greenfield had previous experience in Washington, as a correspondent and a government official. Mr. Sulzberger endorsed his appointment, but it was strongly opposed by Mr. Wicker, by members of the bureau and above all by Mr. Reston. They appealed, and Mr. Sulzberger changed his mind, keeping Mr. Wicker as bureau chief. Mr. Daniel complained to Mr. Sulzberger so angrily about the change of plan that the publisher was offended. Late in 1968, Mr. Wicker stepped aside to write his column full time. He was succeeded by Max Frankel, a bureau member who went on to become executive editor of The Times. Mr. Greenfield, meanwhile, quit the paper. But he was rehired in 1969 as foreign editor and rose to be an assistant managing editor. Mr. Daniel, though, never regained his standing with the publisher. After yielding the managing editor's post in 1969, Mr. Daniel worked in television as well as radio. His assignments included supervising The Times News Service, directing special projects and continuing his service as moderator of a twice-monthly program called ''News in Perspective'' produced by National Educational Television in association with The Times. Mr. Daniel also presided over two radio programs, ''Insight'' and ''One Man's Opinion,'' for WQXR.

Returning to the news staff as head of the Washington bureau, he wrote analytical articles and oversaw the coverage of President Richard M. Nixon's resignation and the outset of Gerald R. Ford's presidency. He concentrated much of his effort on developing a staff for investigative reporting.

Of Murder Mysteries And Truman's Ghost

He also watched his wife's literary career with pride. Margaret Truman Daniel wrote or edited a score of books under the Truman name. After her first mystery novel, ''Murder in the White House,'' became a best seller in 1980, she said in an interview, ''My husband tells me to stick to what I know.'' Her later books have included ''Murder on Capitol Hill'' and ''Murder in the Supreme Court.'' Their son Clifton Truman Daniel asserted in his memoir: ''My mother seems to have a strong opinion, often bad, of almost everyone in Washington. That's why she writes those murder mysteries; so she can kill them all off, one at a time.''

The Daniels had three other sons -- William Wallace, Harrison Gates and Thomas Washington. Late in life the couple saw their home life laid open publicly in a way that was unsettling. In his book, young Clifton, who was a writer for a North Carolina newspaper before becoming an official of Harry S. Truman Community College in Chicago, gave this summary of the problem he said stemmed from having President Truman for a grandfather: ''Grandpa Truman died when I was 15 and I spent my next 11 years wondering how to live up to him. Only I didn't realize that's what I was doing. The only thing I had to show for it was a string of failed academic courses, lost jobs, and hangovers. ''Over the next 10 years,'' he added, ''I found that though I had let my grandfather's fame bring me down, I could look to him to lift me up again. All he would have wanted for me was my happiness.'' Clifton Truman Daniel also wrote that his parents were strict with him and his brothers in other ways because Truman had been president. ''They didn't want us to get the idea that, just because of our grandfather, we could go through life getting something for nothing,'' he observed. ''Looking back, I can see what they were worried about. But keeping us from getting swelled heads often meant bruising our egos.''

In 1977, having reached 65, Mr. Daniel ended his newspaper career and told an interviewer, ''There's no profession that offers you more variety in life or more excitement.'' In addition to his wife and sons, he is survived by five grandchildren. In retirement, Mr. Daniel enjoyed the conviviality of his club, the Century Association, near the Times Building on West 43rd Street. He did not stop writing and went on to be the editor in chief of the book ''Chronicle of the 20th Century.'' Its first edition, a best seller, was published in 1987. The book was a weighty collection of two million words and 3,700 illustrations that listed a news event for almost every day of the 20th century to the end of 1986. Almost all the headlines in the book, and a few of the articles, were written by Mr. Daniel. In an interview in 1987, he said of those articles: ''When something came along where I had some knowledge, I pitched in. I wrote the Hall-Mills murder case because none of the editors had ever heard of it. I also was the only one who seemed to know the details about the Earl of Rosebery, who achieved the three things he wanted in life -- to win the English Derby, marry England's richest heiress and become prime minister.''