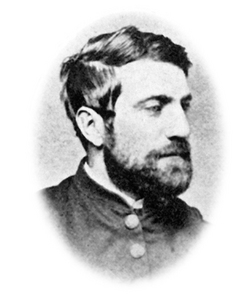

Lieutenant Paxton was in command of Company G during the three days of fighting at Chancellorsville in May 1863. He lamented having to leave the bodies of four of his men on the battlefield. Two months later on July 2 at Gettysburg, Paxton was wounded and captured during the retreat from the Wheatfield. For the next twenty months, he was held in various southern prisons. All during this time, Paxton kept a diary. As he sat under the guard of enemy guns on July 3, he penned the following words: "A captive in my own native state. Nothing to eat. A heavy battle going on. Will we be successful?"

On July 5, he wrote, "On to Richmond as prisoners. 185 officers and about 5,000 men." He arrived at Libby Prison in Richmond, Va. on July 18. Formerly the warehouse of L. Libby and Sons, Ship Chandlers, it was the South's most notorious prison after Andersonville. Only Union officers were kept here. On his first night, guards confiscated the blankets of all the new arrivals and forced them to spend all their money on "chicken snacks." There were no beds or chairs so they slept on the hard dirty floor. The entry for July 31 reads, "Thirteenth day in Libby. Unwell today. Thus has been spent one of the hardest months of my life. Never before did I know what it was to be hungry and have nothing to eat. And tired and sick and could not rest. No blanket to lie upon and no seat to sit upon."

Ten months passed before Paxton was moved to another prison. On May 7, 1864, Paxton wrote, "A sleepless night. Have to leave Libby. But not north. En route for Danville (Va.). Left Libby at 5 o'clock a.m. Took the (railroad) cars…Crowded and warm. Over 90 in a car. No seats and could not sit down."

On July 26, 1864, Paxton was moved again when the Confederates heard that General Sherman had made his way into Georgia. "600 huddle together outside the camp. Take the cars about 3 a.m. Good-bye to Macon…en route for Charleston, S.C. Nothing to eat but corn bread." Once in Charleston, Paxton was first housed in a jail then moved to a workhouse. He "felt like a lost sheep" at being separated from "my old chums." On October 3, Paxton reported that he was "sick all night…pain in the stomach and severe diarrhea followed by a chill and fever." There were already two cases of yellow fever in the building. Two days later, the commandant of the prison and his adjutant both died during the outbreak. The prisoners were immediately evacuated to Columbia, South Carolina in an effort to halt the epidemic.

Paxton arrived at Columbia Military Prison, also known as Camp Sorghum, on October 8, 1864. Not really a prison, it was an open five-acre field of cleared ground without walls, fences, buildings, a ditch, or any other facilities. The guards established the "deadline" by laying wood planks ten feet inside the camp's boundaries. Conditions for existence in this camp were as poor as in the other camps. Cornmeal and sorghum molasses were the main staple, thus the camp became known as "Camp Sorghum." As the weather turned cold, prisoners wore whatever they could find. On October 8, Paxton wrote, "I got a calico gown and towel and handkerchief. Almost froze during the night." On November 2, Paxton wrote, "Oh horrors, what a day. Rained all day. Driven out of our beds before daylight. Have no shelter and had to sit by the fire with a blanket wrapped around me all day. Am wet through and through. Am cook and what a job. Have not read my chapter in the Bible."

On December 12, Camp Sorghum was deactivated and all the prisoners, including Paxton, were moved to the State Lunatic Asylum, hence the name, Camp Asylum. The prisoners were not housed with the mental patients but were confined in a large open space within the asylum walls behind the male dormitory. A board fence was erected to separate the prisoners from the patients. Paxton described it this way: "December 12: Ousted out of our quarters and brought to the yard of the insane asylum, surrounded by a high brick wall. No shelter.…When will these witches get their desserts for their treatment of us as prisoners?" On December 31, he wrote, "Thus passed the year 1864. A blank in the history of my existence. A prisoner of war, knocked about from prison to pen through this vile…Confederacy."

On February 15, 1865, Paxton and about 800 officers left Camp Asylum under heavy guard and were transported north to Wilmington, North Carolina. Two days later, General Sherman's Army burned the asylum to the ground. On February 20, Paxton signed his parole and arrived within Union lines on March 1. He sailed to Camp Parole in Annapolis, Maryland and had a surprise visitor on March 11. His father was there to meet him. The next day, he attended church twice and visited the hospital before leaving on furlough. He arrived in Pittsburgh on March 15, left his measurements for a new wardrobe costing $90 and attended a church prayer meeting at the Sixth Presbyterian Church before departing for Canonsburg.

Throughout his imprisonment, his childhood sweetheart, Miss Emily J. Newkirk, of Wooster, Ohio, wrote to him faithfully. Paxton, still writing in his diary, wrote on March 27: "Would this day were past. Got married at 11 a.m. Started home on the 2:48 train." On April 1, he finally paid a visit to the dentist for some long needed dental care. He returned to Camp Parole to get his pay and learned President Lincoln had been assassinated so he traveled to Washington D.C. to attend the funeral ceremony.

Lieutenant Paxton was promoted to Captain and discharged by special order on May 17, 1865. He practiced law in Pittsburgh for 15 years, then took a position as Examiner for Pensions in the Department of the Interior in Washington, D.C. His wife died on May 21, 1912. They had no children. Shortly thereafter, he retired from his job and returned to Canonsburg to live with his brother, Oliver, on East Pike Street where the borough building now stands. In the home, he kept on display a pair of shoes he bought for $85 Confederate currency while he was a prisoner. Captain Paxton died on August 28, 1918 and was buried in the family plot at Oak Spring Cemetery in Canonsburg.

Lieutenant Paxton was in command of Company G during the three days of fighting at Chancellorsville in May 1863. He lamented having to leave the bodies of four of his men on the battlefield. Two months later on July 2 at Gettysburg, Paxton was wounded and captured during the retreat from the Wheatfield. For the next twenty months, he was held in various southern prisons. All during this time, Paxton kept a diary. As he sat under the guard of enemy guns on July 3, he penned the following words: "A captive in my own native state. Nothing to eat. A heavy battle going on. Will we be successful?"

On July 5, he wrote, "On to Richmond as prisoners. 185 officers and about 5,000 men." He arrived at Libby Prison in Richmond, Va. on July 18. Formerly the warehouse of L. Libby and Sons, Ship Chandlers, it was the South's most notorious prison after Andersonville. Only Union officers were kept here. On his first night, guards confiscated the blankets of all the new arrivals and forced them to spend all their money on "chicken snacks." There were no beds or chairs so they slept on the hard dirty floor. The entry for July 31 reads, "Thirteenth day in Libby. Unwell today. Thus has been spent one of the hardest months of my life. Never before did I know what it was to be hungry and have nothing to eat. And tired and sick and could not rest. No blanket to lie upon and no seat to sit upon."

Ten months passed before Paxton was moved to another prison. On May 7, 1864, Paxton wrote, "A sleepless night. Have to leave Libby. But not north. En route for Danville (Va.). Left Libby at 5 o'clock a.m. Took the (railroad) cars…Crowded and warm. Over 90 in a car. No seats and could not sit down."

On July 26, 1864, Paxton was moved again when the Confederates heard that General Sherman had made his way into Georgia. "600 huddle together outside the camp. Take the cars about 3 a.m. Good-bye to Macon…en route for Charleston, S.C. Nothing to eat but corn bread." Once in Charleston, Paxton was first housed in a jail then moved to a workhouse. He "felt like a lost sheep" at being separated from "my old chums." On October 3, Paxton reported that he was "sick all night…pain in the stomach and severe diarrhea followed by a chill and fever." There were already two cases of yellow fever in the building. Two days later, the commandant of the prison and his adjutant both died during the outbreak. The prisoners were immediately evacuated to Columbia, South Carolina in an effort to halt the epidemic.

Paxton arrived at Columbia Military Prison, also known as Camp Sorghum, on October 8, 1864. Not really a prison, it was an open five-acre field of cleared ground without walls, fences, buildings, a ditch, or any other facilities. The guards established the "deadline" by laying wood planks ten feet inside the camp's boundaries. Conditions for existence in this camp were as poor as in the other camps. Cornmeal and sorghum molasses were the main staple, thus the camp became known as "Camp Sorghum." As the weather turned cold, prisoners wore whatever they could find. On October 8, Paxton wrote, "I got a calico gown and towel and handkerchief. Almost froze during the night." On November 2, Paxton wrote, "Oh horrors, what a day. Rained all day. Driven out of our beds before daylight. Have no shelter and had to sit by the fire with a blanket wrapped around me all day. Am wet through and through. Am cook and what a job. Have not read my chapter in the Bible."

On December 12, Camp Sorghum was deactivated and all the prisoners, including Paxton, were moved to the State Lunatic Asylum, hence the name, Camp Asylum. The prisoners were not housed with the mental patients but were confined in a large open space within the asylum walls behind the male dormitory. A board fence was erected to separate the prisoners from the patients. Paxton described it this way: "December 12: Ousted out of our quarters and brought to the yard of the insane asylum, surrounded by a high brick wall. No shelter.…When will these witches get their desserts for their treatment of us as prisoners?" On December 31, he wrote, "Thus passed the year 1864. A blank in the history of my existence. A prisoner of war, knocked about from prison to pen through this vile…Confederacy."

On February 15, 1865, Paxton and about 800 officers left Camp Asylum under heavy guard and were transported north to Wilmington, North Carolina. Two days later, General Sherman's Army burned the asylum to the ground. On February 20, Paxton signed his parole and arrived within Union lines on March 1. He sailed to Camp Parole in Annapolis, Maryland and had a surprise visitor on March 11. His father was there to meet him. The next day, he attended church twice and visited the hospital before leaving on furlough. He arrived in Pittsburgh on March 15, left his measurements for a new wardrobe costing $90 and attended a church prayer meeting at the Sixth Presbyterian Church before departing for Canonsburg.

Throughout his imprisonment, his childhood sweetheart, Miss Emily J. Newkirk, of Wooster, Ohio, wrote to him faithfully. Paxton, still writing in his diary, wrote on March 27: "Would this day were past. Got married at 11 a.m. Started home on the 2:48 train." On April 1, he finally paid a visit to the dentist for some long needed dental care. He returned to Camp Parole to get his pay and learned President Lincoln had been assassinated so he traveled to Washington D.C. to attend the funeral ceremony.

Lieutenant Paxton was promoted to Captain and discharged by special order on May 17, 1865. He practiced law in Pittsburgh for 15 years, then took a position as Examiner for Pensions in the Department of the Interior in Washington, D.C. His wife died on May 21, 1912. They had no children. Shortly thereafter, he retired from his job and returned to Canonsburg to live with his brother, Oliver, on East Pike Street where the borough building now stands. In the home, he kept on display a pair of shoes he bought for $85 Confederate currency while he was a prisoner. Captain Paxton died on August 28, 1918 and was buried in the family plot at Oak Spring Cemetery in Canonsburg.

Family Members

Sponsored by Ancestry

Advertisement

Advertisement