In 1949, a black man named John Cooper had had enough with Stembridge's outrageous interests rates and dropped off a black, slick sedan at his store. He attached a message that read "You can have this pile of steel for my note." Stembridge was 61 and was extremely angry with John Cooper's act. He grabbed his .38 caliber revolver and headed toward Cooper's home in Shantytown. He took along with him Sam Terry, one of his employees, so he could act as a witness on his behalf just in case anyone saw him. They found him, grabbed him by the T-shirt, and beat him with brass knuckles. Two women came out and tried unsuccessfully to get them off their friend, so Stembridge drew out his .38 caliber revolver and shot wildly wounding both women.

Fleeing for their lives the men made up a story that, in their minds, justified the crime. Terry pleaded that Cooper cursed at them and one of the women pulled out a pistol. Stembridge continued by saying it was plainly self defense. No weapon was found on either one of the ladies. Sam and Marion were accused of murder when one of the women, Emma Johnekin, died in the Richard Binion Clinic. Stembridge was sentenced to 1-3 years of prison. Stembridge appealed the case thinking that he shouldn't have to spend anytime in jail, and he was freed on bond. Marion hired three attorneys for the case. One was Marion Ennis, a young lawyer, district attorney, and state senator. The other two were Frank Evans and Jimmy Watts. Ennis was uneasy about the case and dropped out. The appeal lasted two days and it was proven without a doubt that the bullet that had killed Emma Johnekin was from Stembridge's gun. A 12 man jury labeled him guilty of manslaughter, but Stembridge didn't give up. He appealed to the Georgia courts then to the Supreme Court of the United States. He was then freed because they said he was accused on a prejudiced testimony. Sam Terry had been to court and neither man served time for the crime. Many felt that Stembridge would never be punished because the crime he committed was against blacks.

While Marion Stembridge became richer, Marion Ennis became more and more uneasy about Stembridge not serving anytime in jail. Stembridge had very good political connections and Ennis couldn't rouse a retrial, so he asked help from Stephen T. "Pete" Bivins. At about this time the Internal Revenue Service discovered that Stembridge had not paid his federal taxes in over 10 years. Two agents went over and Marion fixed them with his famous cold-blooded stare that was said to be able to put a hole right through you. He hesitated and then coolly offered them $10,000 to forget the case, but instead on April 28, 1953, he was convicted of bribery and was ordered to appear for sentencing in a week. The people started gossiping and said that Bivins had turned Stembridge in to the IRS. Bivins and Ennis continued to work on the old manslaughter case until they found evidence of perjury.

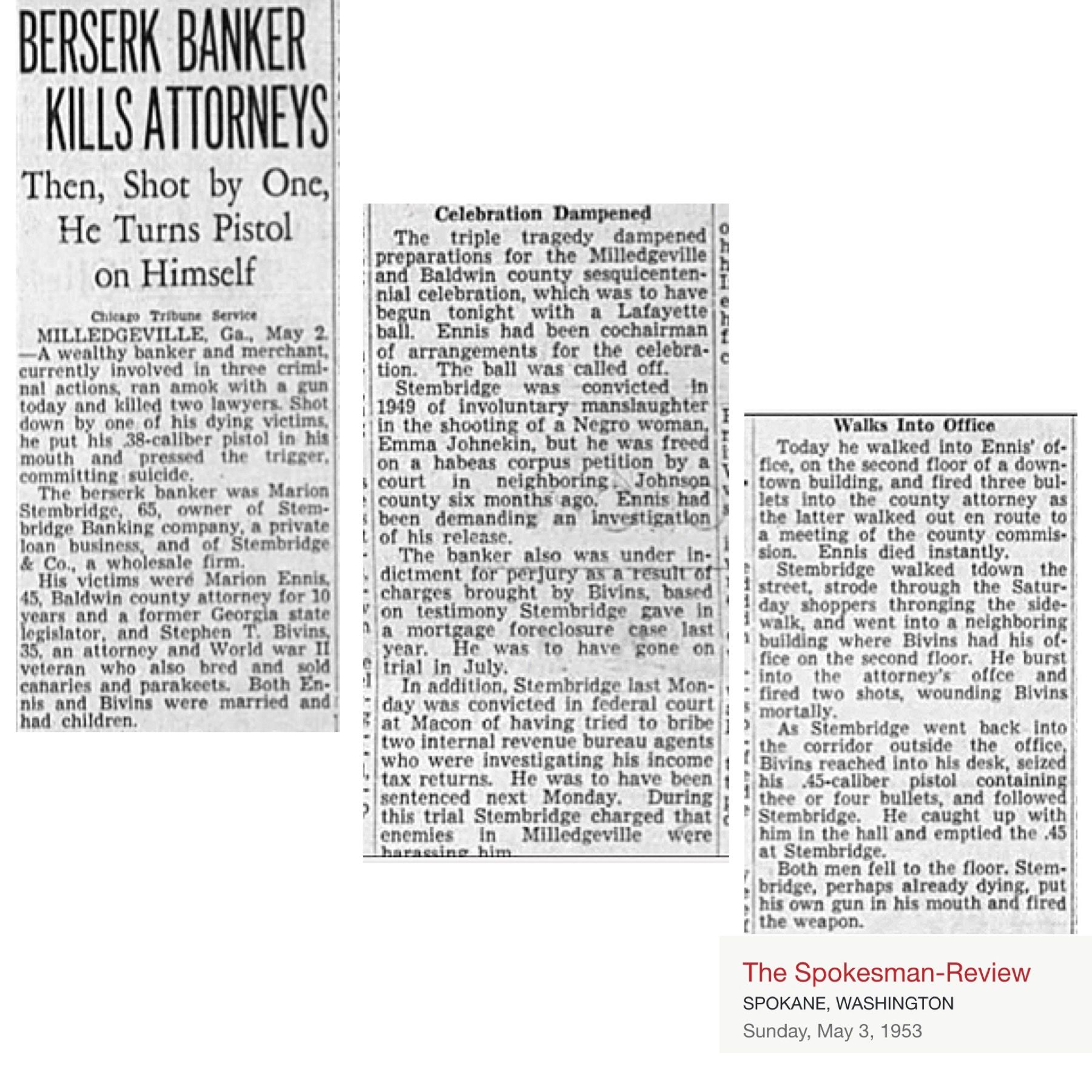

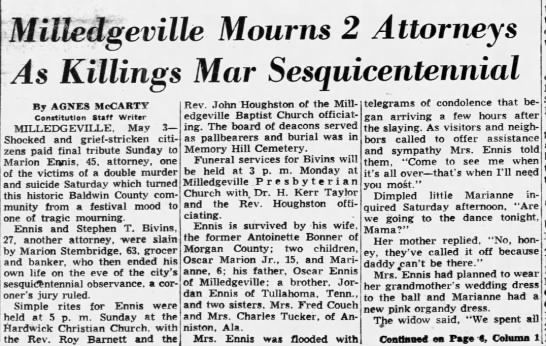

May 3, 1953, was the 150th anniversary of the founding of Milledgeville being state capital. This was the first big celebration in Milledgeville. Marion Stembridge, however, wasn't celebrating. It was two days till he would be sentenced and he knew the judge would send him to prison. As he walked up the stairs from the store cellar, he whistled, nodded to his clerk, and pretended to go invite his mother to go the parade with him. He didn't go to his mother's home, but he went to the office of Marion Ennis. Ennis was shocked to see him and without the slightest hint, Marion pulled out his .38 caliber revolver and shot Ennis three times in the shoulder and chest. Ennis died leaving a widow and two young children.

Stembridge hurriedly walked down to Hancock Street and went to the second floor of the Stanford building to the office of the other attorney Pete Bivins. Stembridge again pulled out his gun and fired once hitting him in the chest. Bivins, who was 27, was able to pull out his pistol, but hadn't the strength to fire it and died. Stembridge then put the pistol in his own mouth and fired, ending his own life along with the two others he had killed.

Peter Dexter wrote Paris Trout, a fictional account based on the Stembridge case, in 1988. It won the National Book Award and was made into a movie in 1991. Residents of the boarding house have reported hearing strange noises in Stembridge's bedroom. Many believe he is still residing there in spirit.

In 1949, a black man named John Cooper had had enough with Stembridge's outrageous interests rates and dropped off a black, slick sedan at his store. He attached a message that read "You can have this pile of steel for my note." Stembridge was 61 and was extremely angry with John Cooper's act. He grabbed his .38 caliber revolver and headed toward Cooper's home in Shantytown. He took along with him Sam Terry, one of his employees, so he could act as a witness on his behalf just in case anyone saw him. They found him, grabbed him by the T-shirt, and beat him with brass knuckles. Two women came out and tried unsuccessfully to get them off their friend, so Stembridge drew out his .38 caliber revolver and shot wildly wounding both women.

Fleeing for their lives the men made up a story that, in their minds, justified the crime. Terry pleaded that Cooper cursed at them and one of the women pulled out a pistol. Stembridge continued by saying it was plainly self defense. No weapon was found on either one of the ladies. Sam and Marion were accused of murder when one of the women, Emma Johnekin, died in the Richard Binion Clinic. Stembridge was sentenced to 1-3 years of prison. Stembridge appealed the case thinking that he shouldn't have to spend anytime in jail, and he was freed on bond. Marion hired three attorneys for the case. One was Marion Ennis, a young lawyer, district attorney, and state senator. The other two were Frank Evans and Jimmy Watts. Ennis was uneasy about the case and dropped out. The appeal lasted two days and it was proven without a doubt that the bullet that had killed Emma Johnekin was from Stembridge's gun. A 12 man jury labeled him guilty of manslaughter, but Stembridge didn't give up. He appealed to the Georgia courts then to the Supreme Court of the United States. He was then freed because they said he was accused on a prejudiced testimony. Sam Terry had been to court and neither man served time for the crime. Many felt that Stembridge would never be punished because the crime he committed was against blacks.

While Marion Stembridge became richer, Marion Ennis became more and more uneasy about Stembridge not serving anytime in jail. Stembridge had very good political connections and Ennis couldn't rouse a retrial, so he asked help from Stephen T. "Pete" Bivins. At about this time the Internal Revenue Service discovered that Stembridge had not paid his federal taxes in over 10 years. Two agents went over and Marion fixed them with his famous cold-blooded stare that was said to be able to put a hole right through you. He hesitated and then coolly offered them $10,000 to forget the case, but instead on April 28, 1953, he was convicted of bribery and was ordered to appear for sentencing in a week. The people started gossiping and said that Bivins had turned Stembridge in to the IRS. Bivins and Ennis continued to work on the old manslaughter case until they found evidence of perjury.

May 3, 1953, was the 150th anniversary of the founding of Milledgeville being state capital. This was the first big celebration in Milledgeville. Marion Stembridge, however, wasn't celebrating. It was two days till he would be sentenced and he knew the judge would send him to prison. As he walked up the stairs from the store cellar, he whistled, nodded to his clerk, and pretended to go invite his mother to go the parade with him. He didn't go to his mother's home, but he went to the office of Marion Ennis. Ennis was shocked to see him and without the slightest hint, Marion pulled out his .38 caliber revolver and shot Ennis three times in the shoulder and chest. Ennis died leaving a widow and two young children.

Stembridge hurriedly walked down to Hancock Street and went to the second floor of the Stanford building to the office of the other attorney Pete Bivins. Stembridge again pulled out his gun and fired once hitting him in the chest. Bivins, who was 27, was able to pull out his pistol, but hadn't the strength to fire it and died. Stembridge then put the pistol in his own mouth and fired, ending his own life along with the two others he had killed.

Peter Dexter wrote Paris Trout, a fictional account based on the Stembridge case, in 1988. It won the National Book Award and was made into a movie in 1991. Residents of the boarding house have reported hearing strange noises in Stembridge's bedroom. Many believe he is still residing there in spirit.

Sponsored by Ancestry

Advertisement

Advertisement