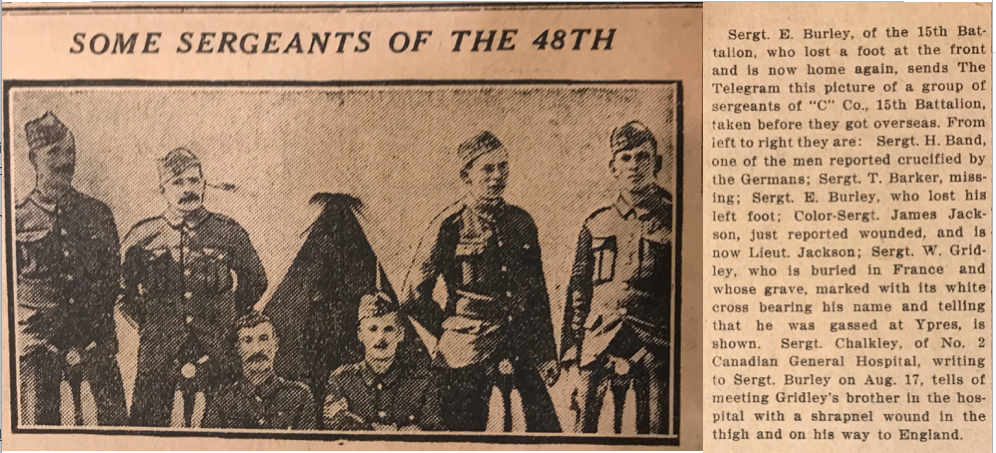

He served three years in the 1st Forfar Volunteers and three years in the 48th Highlanders.He grew up in Dundee on Springbank Terrace, before he decided to leave for Canada in search of work. He found a job in Moncton as a fireman and enlisted in the 15th Bn.,Canadian Infantry. (Central Ontario Regiment)~Service No:27286.soon after war was declared in 1914, quickly rising to the rank of Sergeant.

He was described as a conscientious man and steadfastly refused to drink alcohol. After the war, the Ontario Temperance society, of which he was a member, listed him in their honour roll as having "met death by crucifixion while in the hands of the enemy."

Harry was single, but there is a suggestion of romance. Every month, he sent his wage packet to Miss Isabella Ritchie of King Street, Dundee.

THE CRUCIFIED SOLDIER

======================

This story stems from a piece in The Times of 9th May but appeared in the 10th of May edition, 1915.At the time, even though this was raised in the British Houses of Parliament and for many years afterwards,it was regarded as a myth,fresh evidence has come to light which suggests that it was after all, sadly true.

Canadian soldiers wounded at Ypres had told how one of their officers had been crucified to a wall "by bayonets thrust through his hands and feet" before having another bayonet driven through his throat and, finally, "riddled with bullets". The soldiers said that it had been seen by the Dublin Fusiliers and that they had heard the Fusiliers' officers talking about it.It is possible that the Harry was already dead at the time of his crucifixion and that this was an act of pure war-driven fury towards the enemy.

Harry's nieces and nephews in B.C. had letters sent to his sister,Elizabeth Petrie, after his death, letters written by his comrades-in-arms, testifying he was killed on April 24 and revealing the terrible truth to the grieving relatives.

A typewritten note by a British nurse during the First World War adds weight to the story that a Canadian soldier was indeed crucified with bayonets on a barn door in France by German soldiers in 1915.The note, found in the Liddle Collection of war correspondence in Leeds University, is yet another piece in the puzzle surrounding one of the most famous, mysterious and vicious incidents of the First World War.

The note relates comments by Lance Corporal C.M. Brown to his nurse, Miss Ursula Violet Chaloner, daughter of the first Baron Gisborough. Lance Corporal Brown, apparently recovering from shell wounds, told Miss Chaloner about a Sergeant Harry Band, who "was crucified after a battle of Ypres on one of the doors of a barn with five bayonets in him." This note, dated July 11, 1915, less than three months after the alleged incident, makes it less likely the product of rumour.

In the first weeks of the war, the enemy had committed many barbarous acts on the Belgian civilian population.

On April 24, 1915, George Barrie, a Canadian soldier, took refuge from a gas attack in a home near the French village of St. Julien on the Western Front. The house came under enemy fire and George rushed for cover in a nearby ditch. As it grew dark he saw a group of Germans in a shed about 50 metres away. He lay still and waited for them to leave.

When they were gone, he went to take a closer look at the shed. He saw a man in British uniform leaning against a door near where the Germans had been standing. He called out, but there was no reply. Going closer, he was horrified at what he found.The man, a young sergeant with maple leaves on his lapels, was dead. He was suspended 18 inches from the ground, crucified to the door with eight bayonets.

When it hit the Canadian press, George's story caused a national uproar. Thousands of recruits joined up, eager to wreak revenge on the Boche. A memorial, by British sculptor Derwent Wood, was cast in honour of the dead sergeant. Novels were written and a film, The Prussian Cur, was made. All revealed the horrors of the event to a shocked public.

The Germans denied the atrocity. After the war, they challenged the Allies to prove the crucifixion ever happened. The British Colonial Office launched an official inquiry under a Canadian general. After a lengthy investigation, the inquiry concluded the story was made up. Eyewitness reports were dismissed as confused and conflicting (e.g., the discrepency about how bayonets were used).

Historians have since claimed the story was little more than black propaganda. Like the stories of raped nuns and bayoneted babies reported in the early days of the war, the crucified soldier was a lie, the work of a war effort that hoped to stir up hatred for the Hun.

The story remains elusive, despite the work of several scholars. But one name continues to crop up-that of Sergeant Harry Band. In 1984, art historian Maria Tippett found several documents referring to the incident in the National Archives in Ottawa, but she was unable to say conclusively that it was Harry Band and that he was crucified. Two years later, history professor Seth Feldman of York University took up the story in two CBC Radio Ideas programmes, even interviewing one of Harry Band's relatives in British Columbia who said they had wartime correspondence suggesting Harry Band was the victim of a crucifixion, but nothing definitive.

British military records show Sergeant Band was reported missing, presumed dead, on April 24, 1915, the same day George Barrie reported seeing the atrocity. Harry Band's records even show that his regiment was fighting near St. Julien on that date. True to George's testimony as well, Harry's medical report describes him as 5-foot-11 with brown hair and hazel eyes.

Another fact missed by the official investigation is a file in the Department of National Defence concerning the name of the person to whom the Derwent sculpture, the statue of a soldier being crucified with bayonets, is supposed to be dedicated. The name is, again, that of Sergeant Harry Band, Number 27286.

Why might the Germans have killed Harry in this terrible way? Possibly because two days before he died, Germany launched the first ever gas attack on the Allied lines. Without warning, 180,000 kilograms of chlorine gas were released near Langemark near to where Harry died.

The Allied nations were outraged. The attack broke the international rules of warfare. Canadians were the most bitter.Reports suggest that in retaliation, Canadian troops killed German prisoners in cold blood just as their prisoner comrades had been killed in cold blood.

Harry Band was unlucky enough to be captured by a roving German patrol as his colleagues were avenging their friend's deaths. The Germans showed him no mercy. His crucifixion was probably a warning to the Allies. As the war continued, the story of the crucified soldier was to become part of the gossip of trench life. Terrified for their lives, soldiers would shock each other with tales of what the Germans would do to them if they were captured. Whispers in the trenches embellished the facts surrounding Harry Band's death, and the story attained myth-like status. This would explain why the government commission found so many conflicting reports at the inquiry. Rumour and second-hand accounts made it nearly impossible to find the truth.

The discovery of nurse Chaloner's report, heard so soon after the event, would seem to strengthen the case. When the war was over and the Derwent sculpture, named Canada's Golgotha, was exhibited, Germany objected and Canada, ever anxious to placate, pulled the sculpture from the exhibit and warehoused it for more than 60 years. It has since been on display at the National Gallery in Ottawa.

He served three years in the 1st Forfar Volunteers and three years in the 48th Highlanders.He grew up in Dundee on Springbank Terrace, before he decided to leave for Canada in search of work. He found a job in Moncton as a fireman and enlisted in the 15th Bn.,Canadian Infantry. (Central Ontario Regiment)~Service No:27286.soon after war was declared in 1914, quickly rising to the rank of Sergeant.

He was described as a conscientious man and steadfastly refused to drink alcohol. After the war, the Ontario Temperance society, of which he was a member, listed him in their honour roll as having "met death by crucifixion while in the hands of the enemy."

Harry was single, but there is a suggestion of romance. Every month, he sent his wage packet to Miss Isabella Ritchie of King Street, Dundee.

THE CRUCIFIED SOLDIER

======================

This story stems from a piece in The Times of 9th May but appeared in the 10th of May edition, 1915.At the time, even though this was raised in the British Houses of Parliament and for many years afterwards,it was regarded as a myth,fresh evidence has come to light which suggests that it was after all, sadly true.

Canadian soldiers wounded at Ypres had told how one of their officers had been crucified to a wall "by bayonets thrust through his hands and feet" before having another bayonet driven through his throat and, finally, "riddled with bullets". The soldiers said that it had been seen by the Dublin Fusiliers and that they had heard the Fusiliers' officers talking about it.It is possible that the Harry was already dead at the time of his crucifixion and that this was an act of pure war-driven fury towards the enemy.

Harry's nieces and nephews in B.C. had letters sent to his sister,Elizabeth Petrie, after his death, letters written by his comrades-in-arms, testifying he was killed on April 24 and revealing the terrible truth to the grieving relatives.

A typewritten note by a British nurse during the First World War adds weight to the story that a Canadian soldier was indeed crucified with bayonets on a barn door in France by German soldiers in 1915.The note, found in the Liddle Collection of war correspondence in Leeds University, is yet another piece in the puzzle surrounding one of the most famous, mysterious and vicious incidents of the First World War.

The note relates comments by Lance Corporal C.M. Brown to his nurse, Miss Ursula Violet Chaloner, daughter of the first Baron Gisborough. Lance Corporal Brown, apparently recovering from shell wounds, told Miss Chaloner about a Sergeant Harry Band, who "was crucified after a battle of Ypres on one of the doors of a barn with five bayonets in him." This note, dated July 11, 1915, less than three months after the alleged incident, makes it less likely the product of rumour.

In the first weeks of the war, the enemy had committed many barbarous acts on the Belgian civilian population.

On April 24, 1915, George Barrie, a Canadian soldier, took refuge from a gas attack in a home near the French village of St. Julien on the Western Front. The house came under enemy fire and George rushed for cover in a nearby ditch. As it grew dark he saw a group of Germans in a shed about 50 metres away. He lay still and waited for them to leave.

When they were gone, he went to take a closer look at the shed. He saw a man in British uniform leaning against a door near where the Germans had been standing. He called out, but there was no reply. Going closer, he was horrified at what he found.The man, a young sergeant with maple leaves on his lapels, was dead. He was suspended 18 inches from the ground, crucified to the door with eight bayonets.

When it hit the Canadian press, George's story caused a national uproar. Thousands of recruits joined up, eager to wreak revenge on the Boche. A memorial, by British sculptor Derwent Wood, was cast in honour of the dead sergeant. Novels were written and a film, The Prussian Cur, was made. All revealed the horrors of the event to a shocked public.

The Germans denied the atrocity. After the war, they challenged the Allies to prove the crucifixion ever happened. The British Colonial Office launched an official inquiry under a Canadian general. After a lengthy investigation, the inquiry concluded the story was made up. Eyewitness reports were dismissed as confused and conflicting (e.g., the discrepency about how bayonets were used).

Historians have since claimed the story was little more than black propaganda. Like the stories of raped nuns and bayoneted babies reported in the early days of the war, the crucified soldier was a lie, the work of a war effort that hoped to stir up hatred for the Hun.

The story remains elusive, despite the work of several scholars. But one name continues to crop up-that of Sergeant Harry Band. In 1984, art historian Maria Tippett found several documents referring to the incident in the National Archives in Ottawa, but she was unable to say conclusively that it was Harry Band and that he was crucified. Two years later, history professor Seth Feldman of York University took up the story in two CBC Radio Ideas programmes, even interviewing one of Harry Band's relatives in British Columbia who said they had wartime correspondence suggesting Harry Band was the victim of a crucifixion, but nothing definitive.

British military records show Sergeant Band was reported missing, presumed dead, on April 24, 1915, the same day George Barrie reported seeing the atrocity. Harry Band's records even show that his regiment was fighting near St. Julien on that date. True to George's testimony as well, Harry's medical report describes him as 5-foot-11 with brown hair and hazel eyes.

Another fact missed by the official investigation is a file in the Department of National Defence concerning the name of the person to whom the Derwent sculpture, the statue of a soldier being crucified with bayonets, is supposed to be dedicated. The name is, again, that of Sergeant Harry Band, Number 27286.

Why might the Germans have killed Harry in this terrible way? Possibly because two days before he died, Germany launched the first ever gas attack on the Allied lines. Without warning, 180,000 kilograms of chlorine gas were released near Langemark near to where Harry died.

The Allied nations were outraged. The attack broke the international rules of warfare. Canadians were the most bitter.Reports suggest that in retaliation, Canadian troops killed German prisoners in cold blood just as their prisoner comrades had been killed in cold blood.

Harry Band was unlucky enough to be captured by a roving German patrol as his colleagues were avenging their friend's deaths. The Germans showed him no mercy. His crucifixion was probably a warning to the Allies. As the war continued, the story of the crucified soldier was to become part of the gossip of trench life. Terrified for their lives, soldiers would shock each other with tales of what the Germans would do to them if they were captured. Whispers in the trenches embellished the facts surrounding Harry Band's death, and the story attained myth-like status. This would explain why the government commission found so many conflicting reports at the inquiry. Rumour and second-hand accounts made it nearly impossible to find the truth.

The discovery of nurse Chaloner's report, heard so soon after the event, would seem to strengthen the case. When the war was over and the Derwent sculpture, named Canada's Golgotha, was exhibited, Germany objected and Canada, ever anxious to placate, pulled the sculpture from the exhibit and warehoused it for more than 60 years. It has since been on display at the National Gallery in Ottawa.

Sponsored by Ancestry

Advertisement

Explore more

Sponsored by Ancestry

Advertisement