When Buck Douglas Jr. finally died last week, dozens of workers at Harborview Medical Center crowded into his room. Janitors, food-service staffers, nurses and doctors, they were saying their last goodbyes to a man whose unwavering will to live bested his horrible injuries for 15 years -- long past countless predictions of imminent death and "do not resuscitate" orders.

Outside in the hallway, several dozen more staff members came to pay their respects to Mr. Douglas, 66, and his dedicated caregiver and wife, Marilyn. Many cried, including his doctor, who said his patient had

taught him what it really means to be someone's doctor.

"Buck taught me that people can do amazing things in the face of adversity," said Dr. Kenneth Steinberg, a lung specialist. "He really taught me that the doctor-patient relationship is nothing more than a human-to-human relationship with another person -- and that we're really here to help take care of each other."

Steinberg was there when Mr. Douglas arrived in the hospital's emergency room in 1990, broken and bleeding so badly that the medical team at Harborview, which sees the worst of the worst, never thought he'd make

it for a day, much less 15 years.

They didn't know Buck Douglas.

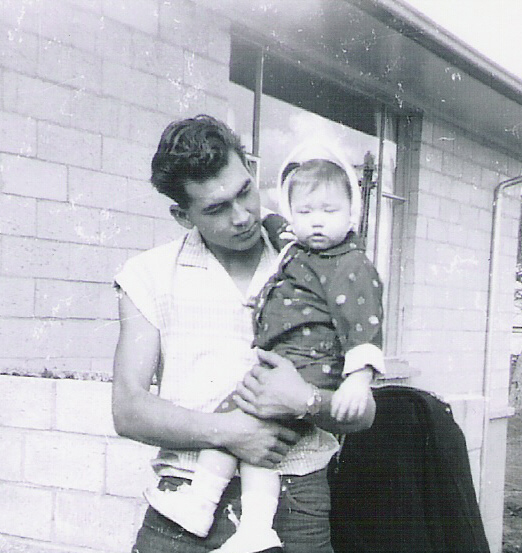

Then, he was a strapping 51-year-old with a penchant for living large.

An Alaska Native who was full blood Eskimo, he was nearly 6 feet tall, a big-shouldered, 300-pound cement finisher who had once raced motorcycles professionally for Harley-Davidson, fished in Alaska and been able to down a prodigious amount of alcohol.

By 1990, he'd given up the alcohol and the racing, but not his motorcycle or his spirit of adventure. At Ocean Shores on that day in late June, he was driving his big Suzuki, his wife behind him, as they headed toward an Alcoholics Anonymous picnic. A truck hit them head-on. The driver, who was later convicted of vehicular assault, was under the influence of alcohol and drugs.

Mr. Douglas and his wife were airlifted to Harborview. She was in critical condition. He was worse. He had been literally disemboweled on the truck's windshield, his entire abdomen exposed as if peeled back with a can opener. His pelvis was in shards, and he was losing blood faster than emergency workers could pump it into him.

"We see a large number of very severely injured people, but he was definitely one of the most severely injured," Steinberg recalls. "At the time, it was fairly unusual for someone as severely injured as he to survive."

Buck and Marilyn, who had married the year before, were wearing helmets, and both escaped head injuries. For Buck, it was about the only part left intact. Along with bone, organ and tissue injuries, he developed a form of lung failure common in critically injured or ill patients.

He spent most of the next year in the hospital's intensive-care unit, pushing teams of surgeons and specialists to chart new waters of care.

"Buck really forced us to think out of the book, and reach for new solutions to problems," said Dr. Hugh Foy, a general surgeon involved in his early care. Some of the medical problems Mr. Douglas developed were then thought to be insurmountable, Foy said. "We had to stand around and watch people die. But Buck wouldn't die, so we had to figure out what to do next."

With her son hovering between life and death, his mother, Ocalena Douglas, rode the bus every day from Federal Way to the hospital. Over and over, recalled his daughter Barbara Olenginski, family members would warn her against hope. "I said, 'Gramma, he's dying.' "

"No," his mother would insist, "he's not -- he'll outlive me."

Mrs. Douglas died in 1996.

Through the years, Mr. Douglas' wife and five daughters from previous marriages spent many hours in Harborview's waiting rooms as he endured surgery after surgery, crisis after crisis. It was there that Barbara,the youngest, met Stanley Olenginski, now her husband.

Family members took a sort of solace in numbers: 225 blood transfusions in the first two years, Barbara counted. Seventy-seven surgeries. Even the doctors counted: In the last year, Steinberg said, Mr. Douglas was in a bed at Harborview 190 days -- more than half the year.

"It got to the point where he defied all powers of medical prediction," Steinberg said.

Doctors said he'd never walk again. But he did, with a walker, and for a time he could drive, as well. Over the years, the walker was replaced by a wheelchair, and Marilyn took over the driving.

His lung problems got worse. Soon, he needed a breathing machine at night. Then his kidneys began to fail, so he needed dialysis. When they learned that no nursing homes were willing to take him with both problems, Marilyn learned to operate the machines. Her stepdaughters, all but one a nurse, were amazed. For the past year or two, at their home in Westport, he was completely dependent on her for care.

"I just did what any wife would do," Marilyn said.

The bills mounted; his private insurance quickly reached its limits, and payments from the driver's insurer were sucked up by the enormous costs. Medicare and Medicaid paid some; Harborview paid some, and the family struggled but managed. The bills, his family and the hospital

estimate, easily totaled $8 million to $10 million.

Some people thought Mr. Douglas, who always insisted on going forward with treatments no matter the risks or the pain, was "in denial," Steinberg said.

"I think he knew exactly what he was facing," he said. Mr. Douglas wanted to be able to get home to see his grandchildren born and grow up, and he did. For that, he was willing to live with pain and "his body deteriorating around him," Steinberg said.

"At times he was ornery, cantankerous, obstinate -- a very stubborn man," he added. "But I think that's what got him so far."

Mr. Douglas, who loved baseball(Mariners), said he didn't want to "go down without swinging," Steinberg recalled. " 'Ken,' he said, 'I'm not ready to

die yet. But if I die, I want to die trying to live.' "

One of his many medical ICU nurses, Liz McNamara-Aslin, found herself constantly amazed at his positive attitude toward his diminishing life. "I wheeled him outside one day last summer," she recalled. "He said, 'I

have it really great -- I have a great life!' "

As he spent more and more time in the hospital, the lives of medical workers became his lifelines to the outside world, McNamara-Aslin said.

"He knew the ages of the janitor's kids," recalled Foy, the surgeon. "The youngest kids who pass the [food] trays, when they would get promoted, they'd come tell Buck. He knew every one of them, their names, where they went to school, their families. He was incredibly invested in

the people there, from the lowest to the highest."

Over the years, Steinberg said, Mr. Douglas taught him to "always be honest and open and treat him like a real person, never try to pull punches or treat him with kid gloves. ... He didn't want you to walk in and say, 'Buck, this is what we're doing.' He wanted you to explain and

talk about the options together."

Finally, though, there were none to talk about.

Mr. Douglas died of respiratory complications last Thursday, April 28, surrounded by family and dozens who knew him as a friend as well as a patient.

"It was hard for me," Steinberg said.

"I cried with them. But I also knew there was nothing else to do; after all I'd done for 15 years, there was nothing left to do but make sure he had a good death. As hard as it was to lose him, I knew it was the

right thing to do. And the right time."

About 100 Harborview workers turned out for Mr. Douglas' funeral Wednesday, marveling with family members about this man who had beaten the odds over and over.

"I was always wondering what he was waiting around for," said his daughter Barbara Olenginski. "I think he wanted to die on his own terms."

When Buck Douglas Jr. finally died last week, dozens of workers at Harborview Medical Center crowded into his room. Janitors, food-service staffers, nurses and doctors, they were saying their last goodbyes to a man whose unwavering will to live bested his horrible injuries for 15 years -- long past countless predictions of imminent death and "do not resuscitate" orders.

Outside in the hallway, several dozen more staff members came to pay their respects to Mr. Douglas, 66, and his dedicated caregiver and wife, Marilyn. Many cried, including his doctor, who said his patient had

taught him what it really means to be someone's doctor.

"Buck taught me that people can do amazing things in the face of adversity," said Dr. Kenneth Steinberg, a lung specialist. "He really taught me that the doctor-patient relationship is nothing more than a human-to-human relationship with another person -- and that we're really here to help take care of each other."

Steinberg was there when Mr. Douglas arrived in the hospital's emergency room in 1990, broken and bleeding so badly that the medical team at Harborview, which sees the worst of the worst, never thought he'd make

it for a day, much less 15 years.

They didn't know Buck Douglas.

Then, he was a strapping 51-year-old with a penchant for living large.

An Alaska Native who was full blood Eskimo, he was nearly 6 feet tall, a big-shouldered, 300-pound cement finisher who had once raced motorcycles professionally for Harley-Davidson, fished in Alaska and been able to down a prodigious amount of alcohol.

By 1990, he'd given up the alcohol and the racing, but not his motorcycle or his spirit of adventure. At Ocean Shores on that day in late June, he was driving his big Suzuki, his wife behind him, as they headed toward an Alcoholics Anonymous picnic. A truck hit them head-on. The driver, who was later convicted of vehicular assault, was under the influence of alcohol and drugs.

Mr. Douglas and his wife were airlifted to Harborview. She was in critical condition. He was worse. He had been literally disemboweled on the truck's windshield, his entire abdomen exposed as if peeled back with a can opener. His pelvis was in shards, and he was losing blood faster than emergency workers could pump it into him.

"We see a large number of very severely injured people, but he was definitely one of the most severely injured," Steinberg recalls. "At the time, it was fairly unusual for someone as severely injured as he to survive."

Buck and Marilyn, who had married the year before, were wearing helmets, and both escaped head injuries. For Buck, it was about the only part left intact. Along with bone, organ and tissue injuries, he developed a form of lung failure common in critically injured or ill patients.

He spent most of the next year in the hospital's intensive-care unit, pushing teams of surgeons and specialists to chart new waters of care.

"Buck really forced us to think out of the book, and reach for new solutions to problems," said Dr. Hugh Foy, a general surgeon involved in his early care. Some of the medical problems Mr. Douglas developed were then thought to be insurmountable, Foy said. "We had to stand around and watch people die. But Buck wouldn't die, so we had to figure out what to do next."

With her son hovering between life and death, his mother, Ocalena Douglas, rode the bus every day from Federal Way to the hospital. Over and over, recalled his daughter Barbara Olenginski, family members would warn her against hope. "I said, 'Gramma, he's dying.' "

"No," his mother would insist, "he's not -- he'll outlive me."

Mrs. Douglas died in 1996.

Through the years, Mr. Douglas' wife and five daughters from previous marriages spent many hours in Harborview's waiting rooms as he endured surgery after surgery, crisis after crisis. It was there that Barbara,the youngest, met Stanley Olenginski, now her husband.

Family members took a sort of solace in numbers: 225 blood transfusions in the first two years, Barbara counted. Seventy-seven surgeries. Even the doctors counted: In the last year, Steinberg said, Mr. Douglas was in a bed at Harborview 190 days -- more than half the year.

"It got to the point where he defied all powers of medical prediction," Steinberg said.

Doctors said he'd never walk again. But he did, with a walker, and for a time he could drive, as well. Over the years, the walker was replaced by a wheelchair, and Marilyn took over the driving.

His lung problems got worse. Soon, he needed a breathing machine at night. Then his kidneys began to fail, so he needed dialysis. When they learned that no nursing homes were willing to take him with both problems, Marilyn learned to operate the machines. Her stepdaughters, all but one a nurse, were amazed. For the past year or two, at their home in Westport, he was completely dependent on her for care.

"I just did what any wife would do," Marilyn said.

The bills mounted; his private insurance quickly reached its limits, and payments from the driver's insurer were sucked up by the enormous costs. Medicare and Medicaid paid some; Harborview paid some, and the family struggled but managed. The bills, his family and the hospital

estimate, easily totaled $8 million to $10 million.

Some people thought Mr. Douglas, who always insisted on going forward with treatments no matter the risks or the pain, was "in denial," Steinberg said.

"I think he knew exactly what he was facing," he said. Mr. Douglas wanted to be able to get home to see his grandchildren born and grow up, and he did. For that, he was willing to live with pain and "his body deteriorating around him," Steinberg said.

"At times he was ornery, cantankerous, obstinate -- a very stubborn man," he added. "But I think that's what got him so far."

Mr. Douglas, who loved baseball(Mariners), said he didn't want to "go down without swinging," Steinberg recalled. " 'Ken,' he said, 'I'm not ready to

die yet. But if I die, I want to die trying to live.' "

One of his many medical ICU nurses, Liz McNamara-Aslin, found herself constantly amazed at his positive attitude toward his diminishing life. "I wheeled him outside one day last summer," she recalled. "He said, 'I

have it really great -- I have a great life!' "

As he spent more and more time in the hospital, the lives of medical workers became his lifelines to the outside world, McNamara-Aslin said.

"He knew the ages of the janitor's kids," recalled Foy, the surgeon. "The youngest kids who pass the [food] trays, when they would get promoted, they'd come tell Buck. He knew every one of them, their names, where they went to school, their families. He was incredibly invested in

the people there, from the lowest to the highest."

Over the years, Steinberg said, Mr. Douglas taught him to "always be honest and open and treat him like a real person, never try to pull punches or treat him with kid gloves. ... He didn't want you to walk in and say, 'Buck, this is what we're doing.' He wanted you to explain and

talk about the options together."

Finally, though, there were none to talk about.

Mr. Douglas died of respiratory complications last Thursday, April 28, surrounded by family and dozens who knew him as a friend as well as a patient.

"It was hard for me," Steinberg said.

"I cried with them. But I also knew there was nothing else to do; after all I'd done for 15 years, there was nothing left to do but make sure he had a good death. As hard as it was to lose him, I knew it was the

right thing to do. And the right time."

About 100 Harborview workers turned out for Mr. Douglas' funeral Wednesday, marveling with family members about this man who had beaten the odds over and over.

"I was always wondering what he was waiting around for," said his daughter Barbara Olenginski. "I think he wanted to die on his own terms."